Category — ICP Exhibit

ICP

Going to the ICP by myself was an interesting experience. I walked through the doors and was instantly confused; I hadn’t known anything of the sort existed. I had seen photography exhibits in famous museums but nothing like the ICP.

I walked around by myself, and said virtually nothing to those around me. I was able to take my time and not have to worry about keeping pace or getting back in time for club hours.

And so I dilly-dallied and took my time looking at the pictures. The two exhibitions, “The Mexican Suitcase” and the “Cuba in Revolution” were not in my favorite genre of photography, but they were impressive just the same. I have seen tons of war photography, but some in particular were fascinating.

My favorite exhibit was the “Cuba in Revolution.” It showed a people in a time of rebellion in the most unorthodox way. It showed celebration, and misery, and victory. It was dirty and extraordinary. It did not show vicious wounds, but those who were fighting for something and a sense of camaraderie in some.

The pictures showed every day people and the excitement in their eyes at the idea of changing something. The shocking part of the exhibit was seeing the iconic “Heroic Guerrilla” picture of Che Guevara that has become a pop culture image. I was used to seeing the polarized, cultured version of the famous rebel’s portrait, but got a chance to see the vintage print.

After checking out the exhibits, I learned that ICP offers photography classes (at a large price). They offer dozens of them, for beginners and experts. It seemed like something worth looking into. Maybe when Santa Claus comes to town, he’ll have ICP in mind.

December 9, 2010 No Comments

International Center of Philosophy

A simple suitcase is able to capture a single momentous time in history that is often forgotten. During the visit to the International Center of Photography, the first exhibit was “The Mexican Suitcase,” which reveals an honest and unaltered aspect of the Spanish Civil War. Upon entrance into the museum, the first visual stimulant was an image of a suitcase, containing rolls of film, purposefully enlarged and placed to introduce the entire exhibit. Upon entering the exhibit, the first photograph I witnessed was of the two photographers, Gerda Taro and Robert Capa. Their works were the focus of the entire exhibit, but the most alarming fact was that they were both romantically involved. This is a fantastic approach because it adds depth to an otherwise formal and plain exhibit. Additionally, it seems like even after death, the photographers Taro and Capa would be forever linked.

As I proceeded further and had the chance to see several photographs, I learned aspects of the Spanish Civil War that certainly would not be discussed in many history courses. The neat order in which photographs were presented in the exhibit kept me highly interested in the topic, and I was able to learn of the traumatizing events that people and nations endured during the war. Beginning with Capa’s photographs, I was able to understand his interest in the war. In his photographs, Capa was capable of embodying the soldiers and their daily activities in a harsh environment. Most importantly, Capa captured photographs of such warfronts, such as the Aragon Front, which revealed the barren and empty areas each soldier had to partake in. This photographer’s style reveals the empty and meaningless nature of the soldiers and the war. Personally, this made it easier for me to visualize and understand the full impact of a war, especially the Spanish Civil War. Another photographer, by the name of Chim, approached taking photographs of the war in a different light. Chim’s photographs presented at the exhibit display themes of religion and its role in the war. From this photographer’s vision I was able to comprehend the importance of religion, its rituals and prayers, to the soldiers. In addition, I learned that religion was intertwined with a certain type of culture found in war.

Although some photographs were easy to study, others were not because of the miniature size of the images. It was sometimes hard to understand what an image portrayed because I would have a difficult time differentiating between the shapes and colors. At certain points during the exhibit, the photographs were made into a collage that was aesthetically pleasing, but hard to distinct as an individual image. Another feature of the exhibit was the silent video documentary on the wall. This was a reasonable attempt to aid individuals during there time, but failed because of the lack of sound. Sound bites often complement our visual perception, and often serve as an effective tool. But this creative addition failed in its utility to further provide further information about the Spanish Civil War or the photographers.

“The Mexican Suitcase” exhibit was small, but powerful enough to convey the historical significance of the Spanish Civil War and life within it. This visit to the International Center of Photography was certainly a crucial part of the curriculum, as it pleasantly surprised me with its content filled with old documents and photographs from the war.

December 8, 2010 No Comments

Fleeting Glimpses

Fred Stein, “Gerda Taro and Robert Capa on the terrace of Café du Dôme in Montparnasse, Paris”

Stepping out of the rain into the International Center of Photography, I welcomed the light and warmth of the building’s entrance and main lobby area. It was when I had caught my breath and started to look up, however, that the true power of the Mexican Suitcase exhibit hit me.

The exhibit consisted of a collection of long lost negatives that were taken during the Spanish Civil War. The three photographers whose works were in the Suitcase (Robert Capa, Gerda Taro, and Chim—real name David Seymour) were all closely involved in documenting the wonders and horrors of this time of turmoil in world history. As I followed the gentle flow of people passing along the length of the carefully crafted exhibit, I found myself surrounded by not only pictures of the actual events of war, but also the documentation—the permanent depiction—of common people who lived during this time: people who breathed the electrified air of discordant opinion. Seeing the faces, the expressions of these people—not just images of soldiers, political leaders—gave new perspective. Often, when we reflect upon history, we envision only those directly involved with wars, battles and conflicts—But what of the rest of the world?

ICP reinforced this revelation by exhibiting different media representations of the conflict: one such example was the French news magazine Regards, which used many of the lost pictures from the “Mexican Suitcase” to actively chronicle the events of the Spanish Civil War. These glimpses, however fleeting, into not only the major events but also the more individualized repercussions of this conflict, gave much more of a platform on which to appreciate both the events themselves as well as the view that the photographers Capa, Taro, and Chim were able to capture in such a turmoil-ridden time.

One aspect of the exhibition that successfully heightened both the emotion and relevance of the photographs specifically, as opposed to what major events they captured, was the curator’s choice to explain the relationship between photographers Capa and Taro. Although they worked together, that was not the extent of their relationship—they were romantically involved as well. Looking at their photography—and seeing pictures of them, smiling and interacting–one can imagine how they saw the images they captured through both a literal and metaphorical lens, as well as the joys (and tragedies) of their relationship. They witnessed these events happening, and we can see the emotion in the faces of those in the photographs–but the exhibit’s efforts to give some background on the photographers’ work allows viewers a tiny, yet significant glimpse into someone else’s reflection on the events they viewed as they were happening: a dramatic revelation that makes our response today, however removed from these events we may be, that much more powerful.

I walked into the International Center of Photography with a dry, simple notion of what happened during some turmoil at some time in history. However, after seeing through the eyes of those who tried so hard to capture the truth, the real events that affected real people—people I’ll never meet, some I’ll never even know the names of—I left with a newfound appreciation of the gravity of the events that affected the people in and around the Spanish Civil War—something that no textbook could ever hope to achieve.

November 11, 2010 No Comments

ICP: Cuba in Revolution

www.nyphotoreview.com/PANPICS/AlbortoICP.jpg

Cuba in Revolution explores everyday life in Cuba before and after the Revolution around the 1950s. This exhibit showed life during a time of turmoil in Cuba and captures the images, faces, and emotions that we don’t usually see. These many photographers managed to take shots of many different aspects of Cuba during these times, including economic, political, and social aspects.

This exhibition shows the tremendous influence of photography in recording the revolutionary movement in Cuba. As I passed each image I noticed the progress and the order of the images. At first it seemed as if the state of Cuba was not under political turmoil. There were a series of photos where there are just many kids and men in the streets laughing and smiling in front of the camera. It had a happy, light-heartened feel to it. But as the photos and years progressed, so did the portrayal of violence and misery. The photos became more impoverished and sad looking.. It focuses on showing us the emotions and story behind the everyday people in Cuba, both involved and not involved in the revolution itself. The revolution affected everyone, and many people were dragged into situations that weren’t very suitable for them. For instance, in a glass window at the exhibit, I saw a newspaper image in which there was an old lady amongst many young men and women, and she was prepared to fight. She looked twice the age of everyone there yet she was being thrown into this mayhem. There was another image of a poor looking boy stuck in the middle of everything. Age didn’t matter. War and violence showed no mercy to anyone. This corrupt time enabled the photographers to capture the affect it had on citizens of all age and size.

The most famous photograph at the Cuban Revolution exhibit as I later found out was the photograph titled, “Heroic Guerrilla”, which showed Che Guevara’s stern brave face. I found it interesting how that is the most famous photo of one of the most influential men in Cuban history… And then right after that picture, there is an entire room dedicated to his death. It went from “heroic” Guevara to “dead” Guevara. To me it embodies the rise and fall of Guevara-Castro and how far one man can fall from grace and lose so much. He went through a certain heroic cycle leading up to his execution and I think that sums up the exhibition itself. The whole exhibition shows this power struggle and the transformation from a solidified nation to one with great chaos.

Overall, I enjoyed my first visit to the ICP exhibit. Cuba in Revolution gave me good insight to not only the revolution itself with the major political figures, but also with the citizens stuck in the middle of everything. These photographs help capture their story and misery in a way we wouldn’t see and understand otherwise.

www.nyphotoreview.com/PANPICS/AlbortoICP.jpg

November 11, 2010 No Comments

ICP: Walking through History

Photography is a coexistence of remembrance and reminiscence in our lives. Like the old black and white photos, memory and history are fused together to project moment through a unique angle. International Center of Photography serves as a storage of various moments of history: it collects and combines different perspectives altogether. The exhibition that I went last Thursday was “The Mexican Suitcase: Rediscovered Spanish Civil War Negatives by Capa, Chim, and Taro” and “Cuba in Revolution.” These photography exhibitions showed how media utilizes photography to control public opinion and manipulate prejudice.

Upon entering the center, we were greeted by a huge image of film rolls showed in a sectored box called “the Mexican Suitcase” in front the main entrance of ICP. The first exhibition contained photos taken by Chim (David Seymour) and other renowned war photographers, such as Gerda Taro, and Robert Capa, who eventually developed war photography as an independent genre. Their tiny suitcases were filled with more than 4,500 35mm negatives of the photos taken during the Spanish Civil War. This was the first time that they were openly exhibited after the films and negatives were lost and found few decades ago.

The most interesting perspective of this exhibition was that it put an emphasis on the influence of using photographs in media. Of course, some of the photos contained horrifying scene of violence, but most of them were depicting the people’s reactions toward the war. The original films and negatives were on the upper wall. Underneath them, there was a collection of magazines from different countries that used one photo to trigger different reactions from people.

Chim (David Seymour), [Two Republican soldiers carrying a crucifix, Madrid], October– November 1936. © Estate of David Seymour / Magnum. International Center of Photography. <http://www.icp.org/museum/exhibitions/mexican-suitcase>

One sector of the exhibition contained a photo, which depicted the Nazi German soldiers forcefully removing the treasures and art pieces from the Spanish Palace claiming that they can preserve them in a better condition. By using the same photo, German magazine praised their government’s generosity and respect toward Spanish culture, while Regards, the French magazine accuses the Nazis of robbery. Even though, the same picture was used for both media, the title and article generated entirely different atmosphere. Media kindly blocked the people’s vision to generate their own interpretation on the photo.

Osvaldo Salas, Comandante Camillo Cienfuegos and Captain Rafael Ochoa at the Lincoln Memorial, Washington, DC, 1959. © The Osvaldo & Roberto Salas Estate, Havana, Cuba, Courtesy The International Art Heritage Foundation. < http://www.icp.org/museum/exhibitions/cuba>

Downstairs, there was an exhibition about Cuban Revolution. Most of the photos were of portraits of the two leaders of Cuban Revolution, Fidel Castro and Che Guevara. There were two photos stuck in my mind. One was of two Cuban officials, Commandant Cienfuegos and Captain Ochoa arrogantly standing in front of the statue of Lincoln at the Lincoln Memorial in their Cuban military uniforms. This uneasy juxtaposition of “the martyrs of communism” standing in front of one of the founding fathers of American democracy was both ironic and amusing at the same time.

Another photo was of Che Guevara’s stunned face with his eyes and mouth wide open. Before I read the credit and information below the photo, I didn’t know this photo was taken after his death. His expression was blank, but it was extremely hard to detect any sign of death in the photo itself. It was the moment when I felt the perception of reality was becoming vague. A photo, which is considered to be the most vivid record of history, could not explain the entire history by itself.

Throughout history, photographs were used as a dominant tool for polarizing opinions in favor of one side. That was my initial preconception toward photography. However, ICP exhibitions made me to redefine the role of photographs in our lives. If capturing the moment is a photographer’s duty, we, as viewers, are in charge of developing our own interpretation with open mind. We can either like it or hate it, but should not disregard the fact that there are always some emotions in our mind evoked by photographs. We should treasure such emotions and insights to avoid perceiving bias from the media.

November 9, 2010 No Comments

Cuba In Revolution

While on a class trip to the International Center of Photography I walked down a staircase and found myself in a visual history lesson of the Cuban Revolution, with time charts, descriptions, and most importantly photographs. These photographs brought history to life for me in a way that only movies, non-documentary films to be matter-of-fact, had done before.

As I walked through the halls of the exhibit I found that films like The Godfather Part II and The Battle of Algiers kept coming to mind. The exhibit started off with pictures of pre-revolution Cuba, in which mostly white people went to clubs and partied in what seemed like a post WWII paradise. As the exhibit went along though, it was soon apparent that there were freedom fighters like Che and Castro who opposed the American backed capitalist puppet government. I watched as Cuba’s prerevolutionary government fell apart as a new communist government was formed.

Knowing some the basic history of the Cuban Revolution, as well as some the major players I tried to, at first, look at the photographs before looking at the written descriptions and the broader explanations that accompanied each set of photos. The museum curators did a good job of setting up the exhibit in a way that allowed visitors to learn something new about an important historical event, but also appreciate the art of photographs.

Obviously there were some striking photographs, like a man sitting on a pole in a crowd of people and Castro shaking the hand of Ernest Hemingway, but what impressed me the most was the juxtaposition of the photos from before, during, and after the revolution. The first photographs I saw were lighthearted and suggested that everything was fine in prerevolutionary Cuba, that it was a peaceful country, some sort of paradise where people could go on vacation and lay on the beaches. But pretty soon, moving on to the next photographs the only thing one saw was the poverty that accompanied peasants in Cuba at the time. The juxtaposition of these images gets to the heart of why the Cubans people resented their prerevolutionary government so much and also demonstrates how photographers choose to persuade or suggest ideas in the pictures that they take.

Later on the tone and content of the photographs shifts dramatically, there is actually a revolution going on in Cuba which culminates on new-years eve 1959 when the famous collapse of the capitalist Cuban government occurs and would change the face of Cuba for half a century and onwards. Instead of white people in dresses and slacks dancing the night away the photographs turned to longhaired, weather-beaten men in military uniform celebrating their victory over the capitalists.

The mood of the exhibit then shifts again to an odd group of photos that portray the rebel leaders Castro and Che in a warmer light while they are taking a vacation. But, alas Cuba is still not perfect as we see the gruesome images of Che’s death in Bolivia. This is an odd group of photographs that sharply contrast one another, yet failed to provide this reviewer with any real commentary.

After this the exhibit seems to tapper out, as the photographs of post revolutionary Cuba are just not as interesting or well placed as the prerevolutionary and revolutionary photos. Another criticism I had was that most of the post-revolutionary photographs were one-sided arguments. They seemed to favor the revolution and did not address the major social and economic issues that faced the new Cuban post revolutionary government. Obviously since it was hard for Westerners to get to Cuba, let alone go to take photos that criticize the country, it might be the case that photos of this nature are just possible to find.

Overall though, Cuba In Revlution is a fully enjoyable and educational experience. It is not only a history lesson, but also a lesson in the use of photography to influence, persuade, and pass judgment on historic events. The exhibit proves that the most persuasive arguments don’t have to be written in the columns or headlines of newspapers, they can also appear as images that choose what to show and what not to show carefully.

November 9, 2010 No Comments

ICP: Cuba in Revolution

Photography is a unique art in several respects. For one, it has the ability to capture a single moment in time unlike any other medium of fine art; a capability that comes especially handy in moments of historical importance. Thursday’s trip to the ‘International Center of Photography’ highlighted two uses of photography during moments of historical significance. In the lower of two exhibits at the Center was Cuba in Revolution, a gallery comprised of nearly thirty different photographers’ work chronicling Cuba from pre-Revolutionary (~1950s) to the death of Che Guevara.

One of the most unexpected political episodes of the Cold War, the Cuban Revolution showed the rest of the world the power that a faction of young Communist rebels could wield. So powerful in fact that the group, led by Fidel Castro overthrew then President Fulgencio Batista of Cuba on January 1st, 1959. If nothing else, the Revolution highlighted the willpower and strength of the young men in Cuba.

Regardless of the photographer, the location, or the date of the photograph, each framed print invariably focused on young male faces, more often then not holding some type of firearm. This particular ‘theme’ lasted throughout the gallery and could not have better captured the events that were taking place in Cuba at the time. The black and white prints, many of which were vintage from the 1960s, also were unique in that a good majority of them possessed a great deal of detail in the background of the photos. Certainly video could have captured the main focus of what was going on in each particular picture, but only a photograph could have assembled the amount of detail that each shot had, essentially freezing a moment in time. And perhaps that is my favorite part of photography, the photographer’s ability to save an instant never to happen again.

Raul Corrales’ ‘La Caballeria’

Several of the photos that were on display were simply astonishing to say the very least. The ‘feature’ photo of the exhibit was Raul Corrales’ La Caballeria, a shot of the mass of horse riding, flag-waving members of the rebel’s cavalry. The shot itself is special as well; as from left to right, perhaps by design, it fails to contain the (perceived) enormity of the number of ‘soldiers,’ another interesting aspect is the great contrast between the white horse leading out in front of primarily darker horses. In a black-and-white print, the contrast stood out even more so because of the large disparity in the colors. My particular favorite of the show happened to be Alberto Korda’s Quixote of the Lamp Post. The photograph gained my liking particularly for its simplicity. It does not use odd angling or false lighting or any other technique rather it relies solely on the photograph’s subject, which is of a man smoking while sitting high atop a lamppost, above seemingly thousands and thousands of people, listening to a speech given by Fidel Castro. The simplicity in Korda’s picture however is not the exception to the set though, but for the most part, the rule. Nearly, if not, all of the photographs on display were of historically significant people or events; that being said, it is likely that each and every one of them were shot in natural conditions, which very well could have been unfavorable towards the photographer. Understanding this only calls for a greater appreciation of the resulting products, which were and still are important in fully understanding the events that transpired in Cuba over the years of the Revolution.

Alberto Korda’s ‘Quixote on Lamppost’

Alberto Korda’s ‘Quixote on Lamppost’

One of the focuses of the exhibit was on Marxist revolutionary, Che Guevara. In many of the photos presented of him, Guevara displayed an almost absence of emotion, whether it be in his military garb in public, or ‘relaxing’ on his own, he consistently and notably expressed a face of indifference. In fact, he was so emotionless that had one not been informed that one wing of photos of him was of him dead; it would be difficult to tell the difference. Perhaps though the most notable of all photos at the exhibit was Alberto Korda’s “Guerrillero Heroico,” a stoic portrait of Guevara, which has famously come to represent ‘rebels’ worldwide. The photo, which has been called one of the greatest of all-time (by some) possesses little by way of artistic technique, rather it merely captures Guevara in a moment of time; therefore it is the subject of the photo which has become renowned as opposed to its technique.

In reality, that same principle held true for just about every other photo on presentation, the greatest photographs on display were not those that were shot with special lenses or those that utilized different techniques; instead they were those whose subject matter meant the most. Considering the purpose of the photos as being documentation of historical events, fortunately they are viewed more so for their subject value as opposed to their skill, which nevertheless was very good.

November 9, 2010 No Comments

International Center of Photography: The Cuban Revolution

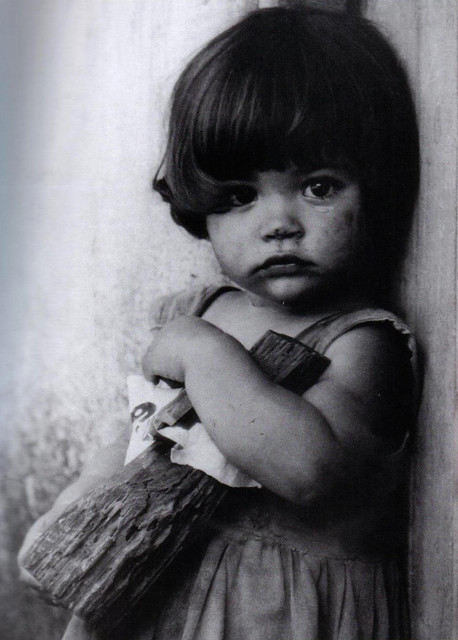

La Nina de la Muneca de Palo by Alberto Korda (1958)

A Cuban Revolution is taking place at ICP’s basement. The works of over thirty photographers are the remaining ancestors of the revolution, capturing the humanity of a people’s struggle to govern themselves.

Today’s daily reminders of the Cuban Revolution are usually one of three things: the Cuban Missile Crisis, the stylish Fidel hat, or a Che Guevara t-shirt. Concerning the third, Alberto Korda’s heroic image of Che, known as the Heroic Guerilla, reminds us of the figure that incited a revolt with Fidel Castro against Batista, a corrupt dictator of Cuba (1940-1944; 1952-1959.) Nevertheless, this polarizing propaganda does little to depict the suffering of the average underprivileged Cuban citizen.

Upon walking around the exhibit, the curator’s design catches your attention. His placement of the pieces disintegrates the reality of life before and after the revolution from the heroics attributed to the years in between. In a brilliant sequence you can find the wealthy celebrating in festive hats at American-installed casinos. In another shot there is a glamorous depiction of a showgirl who could easily be mistaken for a prototype of Marilyn Monroe’s classical white dress image. Then immediately you begin to witness the progression of time right before your eyes as you approach various shots of Che and Fidel Castro: some where Che is posing shirtless like an actor and others where the two are among a stockpile of artillery with a radical joy pasted across their grins.

However, there is one photo that stands out and pressures the viewer to forget about the faces and ideology clouding the revolution. One of Korda’s photographs, La Nina de la Muneca de Palo, would better serve as the face of the movement. A young girl grasping a wooden stub dressed in white fabric like a doll of an indistinguishable gender conjures a figure between a woman dressed in a beautiful white dress or a man in a starched straightjacket; both the tragedies of the revolution. This historic record serves as a reminder of the decline of the wealthy and the blistering insanity of Che’s radical approach.

Among this shot, there are others showing the elderly struggle and the young men raising AK47, the last of which display never before seen photographs of a cold blooded and dead Che. The exhibit is organized chronologically, with photos strategically introducing details that foster the reality of each subsequent shot. Appropriately, viewers are reminded of the historical nature of this exhibit and the fundamental significance of photos as a historic medium, in general.

November 9, 2010 No Comments

Revival of a War

As I made my way through the busy Manhattan street, and entered the International Center of Photography, I was captivated by the simplicity and the modernity of the museum. These characteristics of the museum helped set all of the focus on the exhibit on display (The Mexican Suitcase). The lighting throughout the exhibit was also simplistic, as it didn’t create too dramatic of an effect, and thus, didn’t interfere with the viewing experience. The one problem I had with the simplicity of the exhibit was the presence of a lot of emptiness on the walls, as the photographs covered only an infinitesimal fraction of the walls. In many areas, writing such as the explanation of the exhibit and the Spanish Civil War, and dates could be seen covering up some empty spaces, and although it helped cover more of the walls, overall, it still wasn’t very effective. As for the exhibit itself, the Mexican Suitcase consisted of the works (and techniques) of Robert Capa, Gerda Taro, and David Seymour, and captured all aspects of the Spanish Civil War, from the politics behind it, the actual warfare, the damage inflicted by it, and its societal impact. Their extensive work on the Spanish Civil War allows viewers of the exhibit to revisit and learn about a major historical event.

Some of the best photography from the exhibit was that which displayed warfare. Robert Capa’s work especially (who was my favorite photographer out of the three), gives us the sensation that we are actually in the trenches and the battlefields witnessing the war take place. He creates this feeling through his emphasis on the backgrounds in his photos. One such photograph in which he does this is from the Battle of Teruel, in which two soldiers are looking out through a destroyed building. The focus on the gorgeous backdrop and its sense of proximity really allow viewers to get a scope of the setting, and feel as if they are a part of the photo. Throughout his photographs, not only do we see bleak images of death and destruction, but also of camaraderie and hope. One photograph that really caught my attention was an inspiring photo he took from the Battle of Rio Segre; it was a photo of two soldiers helping one of their wounded companions through uplifted dust. Due to the dust, the photograph appears blurry, and although the three soldiers appear to be the focus of the photo, it’s their emergence from the background that makes them the focus. Robert Capa’s style of photography, in which the environment is emphasized, is one that I really enjoy.

The photography of Gerda Taro and David Seymour seemed to focus more on people rather than backgrounds. Gerda Taro’s photography, which focuses primarily on the people in it, results in some depressing images. In her photography, particularly from her photos of the battle from the Navacerrada Pass, we witness death, injuries, and get a grasp of how formidable the war was. Many of David Seymour’s photographs display and emphasize larger groups of people and their movements. For example, in one of his galleries, which shows a parade in Barcelona commemorating the 19th anniversary of the Russian Revolution, many of his photos focus solely on the large group of people in attendance. The most interesting photo taken by David Seymour that was on display was of a woman nursing her child at a land reform meeting. In this photograph the woman is amongst a large group of people, but is clearly the focus of the photograph. Taro’s and Seymour’s attention on the citizens and soldiers of the Spanish Civil War portrays the societal impact of the war.(http://museum.icp.org/museum/collections/special/chim/pics/b-38.jpg)

Through the combination of the photography styles of Taro, Capa, and Seymour, we really get to see a diverse collection of images from this major historical event. The International Center of Photography does a great job in displaying these photographs for the public to see. The Mexican Suitcase is a tremendous exhibit for fans of photography, and those who want to learn about the Spanish Civil War.

November 9, 2010 No Comments

ICP: Cuba in Revolution Review

The International Center of Photography’s exhibit, Cuba in Revolution provided an incredibly fresh look at familiar faces. What was so impressive about the collection was the immense variety within what was a surprisingly logical sequence of photos. Visitors catch startling glimpses of peasantry, politicians, soldiers, wives and children living through the Cuban Revolution. One is left with a feeling analogous to that of completing a well-rounded book.

What stuck with me the most was ability of so many of the snapshots to suggest a story for your mind to wander upon. They are pieces of art. Some look more like paintings, others like movie screen shots but each has the ability to make you ponder the context.

My favorite pieces were those documenting the faces of Che Guevara. I am not a Che groupie, hat on head, t-shirt on chest, nor do I particularly admire the man but whether you despise or adore him, one must acknowledge that he is fascinating. The exhibit displayed a multitude of Che portraits, among them his most famous print. This famous face was geographically close to a small room where virgin images of the corpse of Guevara were on display- a haunting but slightly beautiful array of images. The sub collection was an impeccably developed reminder of how far anyone can fall.

Cuba in Revolution is the epitome photography exhibit. It captures, documents, and impeccably expresses an entire time period. However for as much as it is documentation, it is also art. The display design brought out the best parts of truly the best photographs and arranged them simply, tastefully and artistically. While The Mexican Suitcase exhibit has the potential to be as classically artsy, because the majority of the photos remain small and are displayed in clusters, individual images are more difficult to fully appreciate.

This was my first trip to the International Center of Photography and I was impressed. The compact premises offered a lot and nothing felt overcrowded. Each exhibit was tactful and fresh; I look forward to returning in the future.

November 9, 2010 No Comments