Category — SBrodetskiy

A Brief on Valeri Shames

Valeri Shames on Coney Island Violence

Valeri Shames is the father of one of my close friends. He engineers architecture and lives with his wife and two children in Boca Raton, Florida, where he works as a freelancer. When I sat down for a ride with Valeri he told me what it was like to come to New York City in 1981, at the age of 19.

A young Ukrainian and his mother moved into a housing project at 124th street and Park Avenue, where his walls crumbled to the point where he could greet his neighbors through the walls.

“That’s how I met my friend girlfriend. She was Hispanic and I was the only white guy in the building.” Shortly after, he moved to Brighton Beach, Coney Island, which was attracting many Ukrainians and Russians with its familiar ocean view. It reminded many of Odessa, a city in Ukraine by the Black Sea. Back in Harlem he didn’t stick out as a sore thumb because of his dark composure, it was safeguard of sorts that helped him assimilate and avoid the violence that would unfold.

He spoke of Slavic people who were leaving the capitulating Soviet Union in search of “a better life.” He described them as ethnocentric, street-wise, go-getters of the American dream. They looked for success in odd jobs off the books and were embarrassed about taking on welfare. They associated welfare with laziness and poverty, which subsequently the associated with blacks in the city housing units.

Eventually, there was a problem. Black gangs and Soviet Russians engaged in a conflict. He didn’t recall who initiated it, but that blacks were driven by territory and Soviets were driven by racism.

Valeri recalled scenes where six black boys attacked two Soviet kids only to have a few Russians join them off the boardwalk for the fight. It wasn’t unusual for teenagers to get into fights. In fact, it was quite common. Kids around Lincoln High School at Coney Island would get into fights after school. Mobs got involved and half a dozen bodies would pave the asphalt, some even comatose.

Valeri was inducted into American culture as an innocent bystander of gang violence. When I asked him if any specific groups were involved, he dismissed the idea of Bloods or Crypts. He reduced it to “the Russians attacked the Blacks and the Blacks attacked the Russians.

These short bursts of reactionary violence lead to better organization and the formation of the Russian mafia. Valeri’s cousin thought he saw an opportunity in their work and joined the trafficking of gasoline across state lines to circumvent taxation. When the operation went belly up the mafia began to pick of their own people with hires who came in from Eastern Europe on temporary visas. His cousin was targeted and survives a gunshot wound to the head, but was blinded in one eye.

His family was a victim of this conflict. Although an unstable and dangerous environment challenged him he took his love for physics to heart. At nineteen he pursued a career in engineering and continued his studies, gaining admission to Stevens Institute of Technology where he got his degree.

We rode on the i95 in his Mercedes E350 out of Boca Raton, Florida to Miami.

“On my left side you’ll see all the rich houses and people who are well off.” On the right you’ll see Little Havana, where bullets come like rain drops and Bed Stuy looks like Beverly Hills.” There was a snicker in his voice that may have been tuned to his success and to the naïveté of the gangs.

December 9, 2010 5 Comments

MoMA

What has happened to art? Why do we accept Picasso, Van Gogh, and Pollack’s work in galleries and museums? The value and price of art can be incredibly subjective, and walking through the Museum of Modern Art makes that even more apparent. Curators deem whether or not something has artistic value and can potentially resonate with the public. And while it is difficult to define “artistic value,” my waltz through MoMA’s abstract quarters left me disappointed.

When I was in kindergarten, I could have clustered randomized shapes and tracings together to substantiate a childish canvas. Later when I took an art class in high school I was able to define such works with a sophistic purpose. Through some vague pretense the viewer may find meaning in a visual sensation, but I don’t think that alone constitutes artistic value. There were paintings that drew esteem from the simple multitude of their strokes and the depth of their texture, but that is not all that is found in the contours of Pollack’s droplets or corners of Picasso’s cubic distortions; they reveal their creator, whether its their intoxication or their dark and pessimistic take on the world, the works are representations of their artists.

I think that this applies to any art form in general, whether it’s dance, poetry, singing, sculpting, or painting, the work should be able to define the artist. A lot of the pieces at the museum fit this description. However, there were a few contemporary or controversial pieces that stood out, depicting the artist’s lifestyle and human struggle. George Maciunas’ “One Year” is a breathtaking exception. This is where simplicity, the abstract, and humanity intersect. When I first saw the wall of fever thermometers, Primatene mist, isuprel, imitation rum, cottage cheese, and grand union instant non-fat dry high grade milk I thought I was staring at an archaic supermarket alley. With further observation my eyes caught sight of the adjacent inhalers, and the products project a picture of a fragile man who suffered from allergies or disease. I didn’t need to read the curator’s description on the side to decipher the value derived from the piece.

Other works, such as the paintings of Jackson Pollack combine distortion, splatter, and a violent form of canvas abuse.

It is this sort of authenticity that was seldom found in MoMA’s abstract exhibit. There was a canvas covered with three virtually indistinguishable shades of black, separated only by the subtly contours of the brush strokes. Another work was a vertical one-inch narrow canvas painted with one stroke of red over gray straight down. The names of these so-called artists are not worth recalling, and carry little merit if they fail to evoke the persona of their creator.

The curator should pick works that create a composition within the room that has a collective and coherent meaning. When observing many of the works the viewer has to tediously inspect the bold descriptions beside the work that scavenges for purpose. MoMA has much to offer presenting some works that are both personally provocative

December 7, 2010 No Comments

On Sara Krulwich

Broadway performances are a sport. There is a sheer athleticism to the hustle and bustle on the stage, remarked Sara Krulwich, the first female photographer at The New York Times. Ms. Krulwich who discussed her monumental venture into photography also depicted the fusion between sports and theater photography.

Here portfolio matched her expertise, and she explained the process behind capturing the climax of a performance, whether a baseball game or a ballet. You have to shoot ahead, she emphasized. The photographer shoots before the swing of the bat, at the very instance the player’s muscles begin to tense up. Theater photography requires the same sort of precision. When switching between slides of opera and ballet, Krulwich spoke of the difficulties in probing theaters for photography, having to challenge the mysticism and credulity of theater. Performers and directors had initially feared the damage uncensored exposure might bring to their performance. The wrinkles that Krulwich may capture in a shot could strip a show of its believability, an incredible power that Krulwich uses sparingly. On the contrary, she isn’t set out to discredit a performance but to capture its best, leaving the criticism to the critics.

There isn’t much mystique to photography. “Sometimes I take fifteen hundred shots, hoping that I’ll get something good,” said Krulwich, who reminding us that while photography isn’t a precise art; it certainly requires vision, skill, and thought.

This is true of herself; she is a pioneer of photography in the historical sense. She usurped on the football field at the University of Michigan when women were banned from the field, yet dogs could perform tricks. She made a spectacle of photography and reporting as she propelled women’s rights in institutions of higher learning and established a diverse and reputable career along the way.

When viewing her photography of theater you can see how she manages to perfectly capture a climactic moment. This not only attests to her technique but to the versatility of photography in various settings. After all, Sara Krulwich is as versatile as her philosophy on life, convincing a room full on aspiring professionals to step out of their comfort zone. As she near several students face-to-face at an unorthodox range, her proximity made a clear point: photography prompts bold and unreserved observations, whether on the street, in the theater, or on the field. “You should be observant in everything you do.”

December 7, 2010 No Comments

Budweiser Tree

On the intersection of East 26th Street and Kings Highway, aside James Madison High School, stands the modern Christmas tree, an aluminum layer cake of red and blue Budweiser cans taped together with flashing Christmas lights, accoutered with the Star of Bethlehem atop.

On the intersection of East 26th Street and Kings Highway, aside James Madison High School, stands the modern Christmas tree, an aluminum layer cake of red and blue Budweiser cans taped together with flashing Christmas lights, accoutered with the Star of Bethlehem atop.

The Christmas tree has a rich history; coming from a Pagan background, it has spread to multiple cultures and religions. In Russia, it is treated as a secular signifying the coming of the New Year. In Christianity it serves as an ornament for the birth of Christ. In Brooklyn, across the street of house, it is a trophy of consumption and intoxication – basically, just celebrating the holidays. Contrary to finding it offensive, I’m fascinated by the range of subjectivity that the tree embodies. From a polytheistic idol to a Christian tradition, its pretty amusing to see the housings of barley malt at their fullest glory: a token to college drinks, football games, and domestic abuse. Traditionally, the tree evokes a sense of family, togetherness, and happiness, but here it achieves a fresher dynamic, commenting on the fun and profane, and the darker side of family life.

P.S. This was written before the Menorah was put up.

November 30, 2010 No Comments

The Scottsboro Boys

The Scottsboro Boys balances historical tragedy and contemporary cynicism to achieve a humorous yet sorrowful dynamic. In a narrative where all characters are played with black male actors, the shuffling of ethnic and gender roles generate a critical outlook on the trail of the Scottsboro Boys, a pivotal moment in history that propelled the civil rights movement. From the start of the play we are told that this production is arguably detailed from the perspective of the boys themselves.

The Broadway musical begins as are recollection of events bearing striking resemblances to circus spectacles that lend credit to the minstrelsy. The conductor is the only Caucasian actor in the plot, and his interaction with the other characters, both in the minstrel and the narrative of the story, serves as a thermometer of race relations throughout the performance. We first see a subjugate nature in their relationship, and later see it dissolved in the rubbing away of blackface paint, or proud tears of struggle. Viewers should be mindful of response the Scottsboro Boys offer to his roles.

The musical relies on the choreography of chair utilization, which are not simply used to prop up the victim of the electric chair or flaunt characters in eclectic dance, but also serve as the skeleton of the scenery. While this approach is clearly frugal, it was appropriate, as the habitual glamour of Broadway may have drained the story of its harsh essence. The lighting was successful in setting the mood: deep warm reds offering moments of passion and cold tones of blue defining bitterness and struggle. Furthermore, warm oranges juxtapose the climatic warmth of the setting to the unsettling passion of the boys.

There is a vibrant synergy between the lighting and the faces of the performers. It radiates like wavelengths and celebrates the phenomenon of Broadway’s energetic world. Aside from the choreography, the unnoticeable nature of the direction attests to the organic flow of the acting. While some critics pointed out that the transition between joy and disaster are weak, they convinced me that I am still watching a musical. The pseudo-manic gestures authenticate the cynicism in the performance. While it was a source of controversy, with figures such as Reverend Al Sharpton raised pickets, actor Joshua Henry who played Haywood Patterson delivered a tear yielding finale that questioned the conservative diction of the picketers. Given the polarizing nature of the musical, reception will vary among the politically sensitive. However, one has little reason to be critical from an artistic standpoint.

The performance has much to offer to the liberal viewer; conservatives beware. In the artistic sense The Scottsboro Boys has a lot to offer, but historians may find the emotional undertones throughout the musical inappropriate and displaced.

November 30, 2010 No Comments

Stock Market

http://www.photodom.com/member/odessa

The New York Stock Exchange is a symbol of the free market: American capitalism at its best. It is at the center of our economic prosperity and our economic downfall. Around it, are its citizens, its innocent, or not so innocent, bystanders who live their lives consciously of its significance, or passionately and independently as artists, with little concern towards the competitive monetary gauge. Herein exists the dynamic the American citizen: poor or rich, white collar or artistic, either a benefactor or a victim of the free market system.

In my collage I tried to express the dynamic citizen that our capitalist society produces: rebel or successor. I used a variety of photos that were taken by my father at different times. The background is a single shot of the New York Stock Exchange, and class distinguishes the overlaying figures around it.

The man on the top left is a random stranger on the street that my father photographed for a dollar. The violinist on the top right is a blend between these two figures, an artist and a professional, producing a unique good as an artist on a quite professional and respectful level. The man beneath him is a junkie from rehab. The one to the left of him is a street performer, perhaps disenchanted by the system, surveying pedestrians for dollar bills like a forgotten muse.

Directly beneath the American flag is your white collar, suit and tie, American success story; a true champion of the free market system, with a private fund manager, enjoying a cigar. At the bottom left of the screen is as Southern fisherman who takes stock only in fresh water salmon, not concerned by the intricacies of the market.

In constructing this collage, I tried to intertwine my two prospective majors: economics and philosophy and provide a visual anecdote of how a single system have propagate a variety of individuals and different stereotypes. Some may say “so what?” but I find it important that a uniform system is interpreted and implemented personally on many different levels, establishing value to perspective.

The American flag is a perfect center because it evokes these very ideas: capitalism, democracy, freedom of expression, and individualism. It networks these individuals through a common authority in their livelihood. In some respect each one of use belongs in this collage; we are in no way discounted from its composition, neither by mentality nor by social consensus.

I composed the piece by taking my fathers works and manipulating them with various filters that give them an artsy appearance. Brush strokes were simulated to accentuate the details in the images before the photographs were cut out and blended onto a background. The lighting and contrast for each figure was adjusted and was set to distinguish each person from one another, not to sell them as a uniform group. In essence this photograph is a memorial of American life: socially and economically, artistically and professionally, offering insight on the dynamic of our country’s life.

The New York Stock Exchange is a symbol of the free market: American capitalism at its best. It is at the center of our economic prosperity and our economic downfall. Around it, are its citizens, its innocent, or not so innocent, bystanders who live their lives consciously of its significance, or passionately and independently as artists, with little concern towards the competitive monetary gauge. Herein exists the dynamic the American citizen: poor or rich, white collar or artistic, either a benefactor or a victim of the free market system.

In my collage I tried to express the dynamic citizen that our capitalist society produces: rebel or successor. I used a variety of photos that were taken by my father at different times. The background is a single shot of the New York Stock Exchange, and class distinguishes the overlaying figures around it.

The man on the top left is a random stranger on the street that my father photographed for a dollar. The violinist on the top right is a blend between these two figures, an artist and a professional, producing a unique good as an artist on a quite professional and respectful level. The man beneath him is a junkie from rehab. The one to the left of him is a street performer, perhaps disenchanted by the system, surveying pedestrians for dollar bills like a forgotten muse.

Directly beneath the American flag is your white collar, suit and tie, American success story; a true champion of the free market system, with a private fund manager, enjoying a cigar. At the bottom left of the screen is as Southern fisherman who takes stock only in fresh water salmon, not concerned by the intricacies of the market.

In constructing this collage, I tried to intertwine my two prospective majors: economics and philosophy and provide a visual anecdote of how a single system have propagate a variety of individuals and different stereotypes. Some may say “so what?” but I find it important that a uniform system is interpreted and implemented personally on many different levels, establishing value to perspective.

The American flag is a perfect center because it evokes these very ideas: capitalism, democracy, freedom of expression, and individualism. It networks these individuals through a common authority in their livelihood. In some respect each one of use belongs in this collage; we are in no way discounted from its composition, neither by mentality nor by social consensus.

I composed the piece by taking my fathers works and manipulating them with various filters that give them an artsy appearance. Brush strokes were simulated to accentuate the details in the images before the photographs were cut out and blended onto a background. The lighting and contrast for each figure was adjusted and was set to distinguish each person from one another, not to sell them as a uniform group. In essence this photograph is a memorial of American life: socially and economically, artistically and professionally, offering insight on the dynamic of our country’s life.

November 23, 2010 1 Comment

B&H Photo Video

- Intellectual Property of B & H Foto & Electronics Corp

If you ever need a simple memory card reader for your camera and would like to immerse yourself in a “culturally enriched” atmosphere, you should check out B&H Photo Video on 34th street and 9th Avenue. It may be the most unique store in Manhattan. As you enter you’re greeted twice. Continuing to walk down a wide hall with a fork in the road, you’ll find product department maps hanging above your head and a third person to greet you and help you navigate your way about the superstore. Cameras, phones, computers, cell phones, alarm clocks, batteries, and little fuzzy pouches for your iPod nano are about.

The first thing you’ll notice is the assembly line that hovers products either overhead or behind counters. My little six dollar card reader would be bagged by one of employees catering to fifty or so booths at the photography department, dropped into a green plastic tray that’s tagged with my receipt, and routed to the pick-up area. I’d take a receipt and make my way back down the stairs, as the escalator goes only upwards, and head to the payment area, where one of four cash clerks or one of ten credit card clerks will take my money from me and offer me another receipt to pickup my purchase. The process is systematic and the methodology is brilliant and efficient to an extent.

Virtually every person working at the department counters is male and Orthodox Jewish. The salesmen who work the floor are male Orthodox Jews. The cashiers that handle the money are male Orthodox Jews. The information guide, however, was a Hispanic woman. The second person to welcome me in after the doorman was a Hispanic woman. The person who checked in my bag was a Black man. The person who looked for and gave me my purchase of the assembly line was a Hispanic man. The person who gave me back my backpack at the bag check this time a Hispanic man.

I thought that something was wrong, that there was a certain level of discrimination that should have already resonated in legal channels, but in reality this was the solution. In October 2007, B&H settled a multimillion-dollar lawsuit for discriminating against Hispanic workers. In November 2009. B&H was sued for $19 million for refusing to hire and discriminating against women. Status: Pending – go figure.

The stores track record and current atmosphere is allegorical of America’s history in general. Our system is extremely efficient and productive; we champion services rather than production to other; we departmentalize our government with bureaucratic scrutiny, but disappointingly we still champion discrimination de facto.

Addendum

This is absolutely not intended to singling out Orthodox Jews as racists, but to provide an example that illustrates the stark reality of general discrimination in American society. It just so happens that this was the store I went to and found a blatant contrast in job detail vs. gender and ethnicity.

November 16, 2010 5 Comments

Svyatoslav Brodetskiy / Think

[photosmash=]

When I set out to build my portfolio I realized one thing: I would be a godlike photographer if I could freeze time and assume any angle for my shot. However, things aren’t that simple. Photography takes courage and a certain artistic sort of confidence that reciprocates the esteem of the introvert poet. Any of my former art endeavors were rooted in the latter, and this influenced my approach to taking these photographs. I used a Sony DSC-TX7 point-and-shoot camera that was essentially at belly button level and I just took countless random photos as I was making laps around Union Square park, the almost cliché cultural center of urban life in Manhattan. The products were absolutely random, but I accomplished the imaginary. I froze time and saw what I wanted to see. I tried to produce the photos that I would have taken if I could defy the laws of physics and move myself about like a phantom. To accomplish this, I flipped through the random photos and cropped the photos by applying my perspective, some of the cropped material comes from just 10% of the original photo. In some instances I took just one face out of fifteen and developed a single canvas for that head. It’s difficult to defend this approach and, aside from Union Square’s urban clustering, it may be difficult to pick up a solid theme through the portfolio, but what I focused on in creating these images was the subject’s expression of thought or physiognomy.

I wanted to elicit questions from the viewer, for him to wonder what the subject was thinking. Of course there isn’t a straightforward answer, and in some cases there are several faces in a photo juxtaposed against one another. In a particular photo there are two women engaging in a conversation and a homeless person with his or her head retired upon his lap. I interpreted these two subjects as emotional polarities, and picking them out and producing them in this sort of juxtaposition was essentially what I set out to do.

All the shots were produced in black and white (or grayscale) because I felt that the color wasn’t necessary to illustrate the subject’s thoughts or expression. On the contrary, removing color creates a more reliable medium and allows the viewer to focus on the natural and human aspects in the picture, rather then getting distracted by the vibrant commercialism of New York City. I was not trying to make my photos vintage per se.

In one way, I felt that I drew inspiration from Philip-Lorca diCorcia. I took a series of candid photos but also arbitrarily imposed my reality onto the image. While diCorcia didn’t blatantly crop his photos and I didn’t exploit lighting in mine, there is a blend of his methods that influenced my style.

I did not use a specific naming system because I did not want to predispose the viewer to a particular perception. Instead I stated the obvious.

November 16, 2010 5 Comments

International Center of Photography: The Cuban Revolution

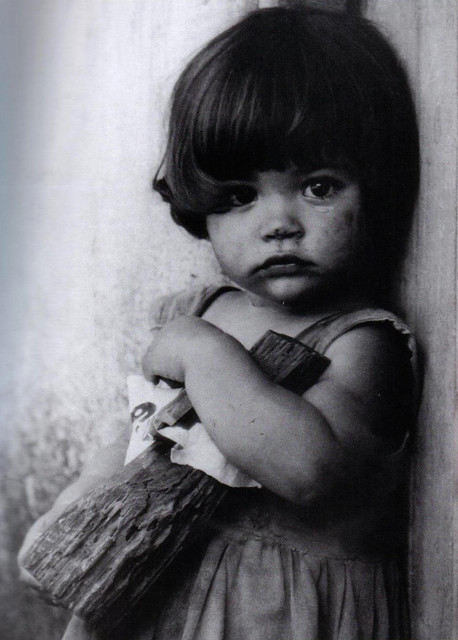

La Nina de la Muneca de Palo by Alberto Korda (1958)

A Cuban Revolution is taking place at ICP’s basement. The works of over thirty photographers are the remaining ancestors of the revolution, capturing the humanity of a people’s struggle to govern themselves.

Today’s daily reminders of the Cuban Revolution are usually one of three things: the Cuban Missile Crisis, the stylish Fidel hat, or a Che Guevara t-shirt. Concerning the third, Alberto Korda’s heroic image of Che, known as the Heroic Guerilla, reminds us of the figure that incited a revolt with Fidel Castro against Batista, a corrupt dictator of Cuba (1940-1944; 1952-1959.) Nevertheless, this polarizing propaganda does little to depict the suffering of the average underprivileged Cuban citizen.

Upon walking around the exhibit, the curator’s design catches your attention. His placement of the pieces disintegrates the reality of life before and after the revolution from the heroics attributed to the years in between. In a brilliant sequence you can find the wealthy celebrating in festive hats at American-installed casinos. In another shot there is a glamorous depiction of a showgirl who could easily be mistaken for a prototype of Marilyn Monroe’s classical white dress image. Then immediately you begin to witness the progression of time right before your eyes as you approach various shots of Che and Fidel Castro: some where Che is posing shirtless like an actor and others where the two are among a stockpile of artillery with a radical joy pasted across their grins.

However, there is one photo that stands out and pressures the viewer to forget about the faces and ideology clouding the revolution. One of Korda’s photographs, La Nina de la Muneca de Palo, would better serve as the face of the movement. A young girl grasping a wooden stub dressed in white fabric like a doll of an indistinguishable gender conjures a figure between a woman dressed in a beautiful white dress or a man in a starched straightjacket; both the tragedies of the revolution. This historic record serves as a reminder of the decline of the wealthy and the blistering insanity of Che’s radical approach.

Among this shot, there are others showing the elderly struggle and the young men raising AK47, the last of which display never before seen photographs of a cold blooded and dead Che. The exhibit is organized chronologically, with photos strategically introducing details that foster the reality of each subsequent shot. Appropriately, viewers are reminded of the historical nature of this exhibit and the fundamental significance of photos as a historic medium, in general.

November 9, 2010 No Comments

Fix

It’s been three weeks since I’ve abandoned coffee. In my efforts to stifle my caffeine consumption, I switched to tea. “Did you know tea has more caffeine than coffee?” came the rhetorical question. “No. No, I didn’t, and let’s keep it that way.”

I guess it was an illusory transition, but I’ve been raised since birth accepting that tea is generally good for you. Upon realizing that I was sick, my parents treated me as a funnel. Apparently, a hot cup of earl grey soothes the sore throat, and it was a simple way to smuggle some vitamin C from a squeezed lemon past my taste buds. When I was ill, it came down to six cups a day, and tealeaves took temporary residence on the food pyramid. Perhaps, that is the just the culture my family keeps; it’s simpler elsewhere.

In England, there is teatime: a national afternoon break for a lovely cup of tea. In China, green tea is a common serving of hospitality for guests. In America, it’s a venti caramel dolce latte a couple of times a day until you’re crashing like a heroin junkie, or the lesser known Tea Party – your choice.

I can’t tell if our consumption culture has relieved traditional duty or if there never was a traditional, American, approach to tea or coffee. I remember reading once, that Americans adopted coffee because it was cheaper than tea, and treated it as a symbol of independence after the Boston Tea Party. Certainly, they stuck it to the man. I’m not sure if our founding fathers would have made themselves at home at their residential Starbucks, sipping away their frappe like today’s coffee shop intellectuals. But it certainly seems to be the American thing to do.

Count me out; I’m rebelling against the charred bean corporate coffee culture. Maybe that’s the American thing to do. I can start my own culture, and call it the Tea Union, or the Tea Boys, or better yet the Tea Party. Maybe I can take your cup of coffee and turn it into my cup of tea. If I did, would you vote for me?

November 2, 2010 No Comments