“Huh?”

Yeah, that’s what I thought too. It’s possibly the single least likely phrase I expected to stumble upon in a book about an artist. But there it was. Out of context, I suppose it really doesn’t make any sense. But if I said that the book I was reading was about M.C. Escher (called The Magic of M.C. Escher), it would probably be an “Aha!” moment.

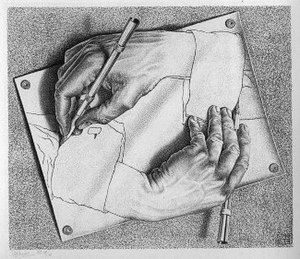

Escher's famous "Drawing Hands" explores the idea of paradoxes and "strange loops"

The well-known, innovative 20th century artist M.C. Escher was the creator of, in a phrase, “art for science and math lovers.” Infinity, polyhedra, geometric distortions, tessellations, impossible constructions – they’re all there somewhere in his work. Crazy, no? He didn’t even have any formal mathematical training. That’s even crazier.

I cannot pretend to comprehend much of what I read about him. There isn’t exactly a lot of discussion about technique and aesthetic. Instead, it’s more about Penrose triangles and orthogonal forces of gravity. Not quite the type of thing that I like to involve myself with. I have nothing against it. I just admittedly don’t understand much of it. That’s what I think makes Escher so remarkable. I’ve spoken to quite a few Mathletes about art, and many of them told me that they just don’t “get” it. It’s markedly outside their comfort zone. Well, here comes Escher to the rescue. Scientists and mathematicians arguably enjoy his work more than anybody else.

It’s a remarkable feat, but Escher effectively managed to tether the worlds of art and technical logistics in a way that I do not believe anyone ever has. I mean, it’s art that penetrates a world that is inhabited by its theoretical opposite. In that way, it’s art that almost transcends the barriers that usually serve to confine it. We’ve talked a lot about the ever-expanding artistic intersection in our class – which includes politics, industry, and commerce, among others – and I think that Escher, with his mind-boggling work, adds mathematics to the list. So to those with a penchant for science I say you’ve found a remarkable associate in Escher. To those who are not quite so scientifically inclined (myself included) I say Escher is yet another brilliant artist to marvel at.