Contents

Introduction

Air Quality

Interview with Friends of Hudson River Park

Energy Use

Construction Impacts

Natural Resources

Public Health

Solid Waste

Hudson Square Community

Development

Polling the Community

Court Case

Conclusion

Sources

Introduction

The Hudson Square Garage will house sanitation trucks that will serve the community in which it is build. “The new Manhattan 1/2/5 Garage, a five-level structure approximately 147 to 150 feet in height at the street wall (site elevation varies) plus roof top mechanical equipment, would have a total net floor area of approximately 427,250 square feet of space(1).” There would be a nearby salt shed build as well. A stormwater pollution prevention plan would be used when constructing the garage to reduce the impact on the environment. The garage would be functioning 7 days a week 24 hours a day. The sanitations trucks located in the garage would be equipped with Clean Diesel technology, which would “reduce vehicle particulate emissions substantially to levels comparable to those from trucks fueled by compressed natural gas(1). ” Trees would be planted in the vicinity of the garage to lessen its impact on the environment. The garage is being built in a relatively rich, white neighborhood, so there is not a strong environmental justice issue for the building of the garage. Nevertheless, the battles about its construction have been heated, and involved many influential celebrity figures. When the plan for the building of the garage was circulated within the community and after debate, certain concessions were made. This included moving the salt shed to Manhattan District 1 Garage and equipping the trucks with Diesel Technology that would reduce pollution.Even though many alternatives were proposed by the community, none were accepted.The Department of Sanitation(DSNY) considered building three separate district garages in separate buildings, in addition to a salt shed. DSNY found that acquiring land and construction costs in Manhattan would make this project impractical for Districts 1, 2 and 5(2). At this point, the garage is being built, and it appears that it will continue to be built until its completions despite various lawsuits that were filed against its construction. This project explores the impact of the Hudson Square Sanitation garage on the environmental and delineates various issues that arose due to the building of the garage between the city, the community and organizations such as Friends of Hudson River Park.

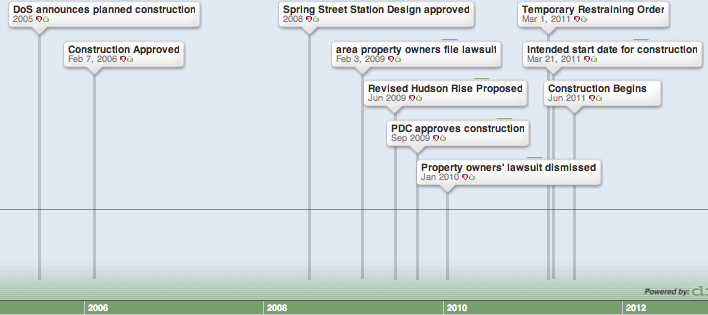

Timeline of Hudson Square Garage Development

Air Quality

Even though the facility and the trucks it houses would obviously have a negative impact on the environment, its impact is not significant enough to warrant serious alarm because its operation would have a similar impact to many other industrial facilities. No unavoidable adverse impacts to the environment were found in connection with operation of the facility.

If the operation of a facility is to have significant impact on health and the environment, it must exceed legal limits set by the government. However, this was not the case for this sanitation garage because all studies concluded that all emissions would not break established laws. For example, it was stated in the environmental impact statement that, “By 2010, all new DSNY heavy duty truck diesel truck purchase will be required to meet the more stringent USEPA 2010 NOx standards of 0.2 grams per brake horsepower hour (g/bph-hr) of NOx, compared to 6 g for 1990 trucks, 5 g for 1991-97 trucks, 4 g for1998-2003 trucks, and 2.5 g for 2004 to 2006 trucks.” Due to the fact that the trucks will meet high standards for emission of nitrogen oxide, no tests were carried out regarding Nitrogen Oxide( NO) emissions because operation of facility would not produce NO levels that violate standards. United States Environmental Protection Agency(USEPA) is federal agency responsible for maintaining the environment, and thus can be trusted to impose standards that would prevent significant impacts to the environment and human health(2).

Particulate Matter(PMs) are created via vehicle emissions and facility heating. Those facilities that produce 10 ton of PM annually or more could have relevant adverse impacts. However, the building of the garage and operation of trucks that it houses would not produce this amount annually and would not surpass the threshold(maximum) legal limit of PM(2). Thus, once again it can be seen that the operation of the facility will not break the environmental regulations, which determine whether such a facility would be safe.

The building of the garage and operation of the sanitation trucks that it will house would produce no significant amount of lead, so investigation of lead was not conducted, which was also the case for NO(3).Additionally, it was deduced that there would not be significant impacts due to Carbon Monoxide(CO) emissions that could result in adverse health impacts and damage to ozone(2). The sanitation garage itself will use steam, instead of natural gas and thus there would be no emissions from the sanitation’s garage’s water systems and heat systems(2). Due to the fact that there would be an increased about of sanitation vehicles, unpleasant odor would certainly be present in the facility area. However, the odor impacts will not be considerable. For example, in studies the odor of the worst smelling trucks could only be detected from 4-5 feet away(2).

Non-Criteria Pollutants can have a relevant impact on environment and human health. Like PMs, these pollutants are caused by operation of cars, trucks and operation of construction equipment. Small amounts of 16 types of non-criteria pollutants(toxic-air pollutants) are known to be emitted from diesel trucks. These pollutants are of two types: carcinogenic pollutants and non-carcinogenic pollutants. However, “…NYSDEC has established acceptable ambient levels for these pollutants based on human exposure criteria.” It was concluded that diesel emission would not results in significant adverse impact to air quality and would not produce important health risk. This is because the garage trucks would contain highly controlled emissions(2). Thus, even though it is understood that the trucks will have emissions that are bad for health, these emissions will be highly controlled, and will not be present in large enough quantity to seriously affect air quality.

The sanitations trucks located in the garage would be equipped with Clean Diesel technology, which would “reduce vehicle particulate emissions substantially to levels comparable to those from trucks fueled by compressed natural gas. In addition, most of the DSNY cars and small vehicles garaged at the facility would be alternate fuel vehicles (such as ethanol E85 or hybrid gas/electric).” Clean Diesel technology reduces the carbon footprint and thus does not cause significant ozone layer damage. Clean diesel technology reduces levels of CO, HC(Hydrocarbons), and Nitrogen Oxides. Green building features would be incorporated into the garage, which would improve energy efficiency, and reduce toxicity levels produced by operation of trucks and by the garbage they collect(2). However, there are disadvantages to clean diesel technology, as have been proven by the World Health Organization.

According to the World Health Organization,” Shifting from gasoline- to diesel-powered engines to lower CO2 emissions could increase emissions of health-damaging small particulates (PM10, PM2.5) per unit of travel.5 IPCC’s review of diesel technology’s potential does not consider potential health impacts; yet large shifts to diesel fuels in European cities in the last decade are considered to be a cause of stable (not lower) PM10 levels in European cities in the last decade and no decline in the health impacts of air pollution – despite the introduction of cleaner diesel technologies”. Thus, the trucks could have a negative impact on the health of the community, even though carbon dioxide(CO2) levels would be reduced(3).

All motor vehicles produce emissions that decrease air quality and have a negative impact on the environment. Clean Diesel technology helps to reduce this impact, but does not eliminate negative consequences of operations of vehicles. The operation of these trucks and the facility it houses does not break any environmental regulations, which ultimately determine if the operation of the facility is safe for the environment and community.

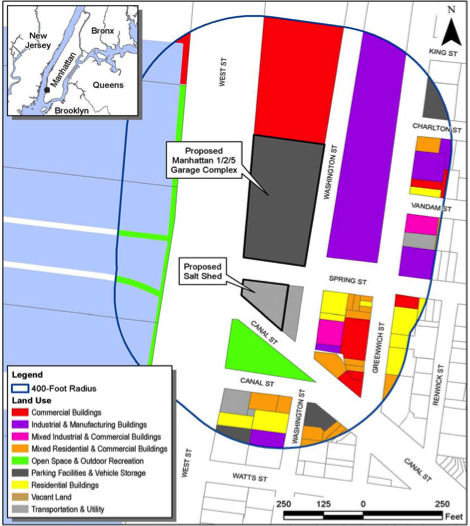

Residential map of Hudson Square (18)

This is a table with air quality standards for New York and the rest of the nation. These standards display the stringent regulations that exists regarding air quality and various emissions, further highlighting the validity of Department of Sanitation’s claims that the Hudson Square Garage will not have a significant adverse impact on air quality since no regulations regarding standards were broken(1).

This is a table with air quality standards for New York and the rest of the nation. These standards display the stringent regulations that exists regarding air quality and various emissions, further highlighting the validity of Department of Sanitation’s claims that the Hudson Square Garage will not have a significant adverse impact on air quality since no regulations regarding standards were broken(1).

Interview with Friends of Hudson River Park

Alex:Can you elaborate on the lawsuits that took place regarding the building of the Hudson Square Garage?

Mr. Pietrantone :The FOHRP filed lawsuit against city to move the garage to free up space for the Hudson River Park park.I testified in a city council hearing that Hudson Square Garage should be relocated from its intended construction site and that the Friends of Hudson River Park would extend deadline that they posed. The FOHRP do not want to make choices between one community and the other. However, the city did not accept the alternatives.

Alex:What is the urgency of moving the garage?

It is a park land. Access to waterfront is important, it’s a basic right of citizens.

Alex:How do you think community organizations or nonprofits impact government decisions that mandate building of such facilities?

Mr. Pietrantone:Depends on the issue and degree of political support. The city council speaker sided with the administration about the movement of garage to Hudson Square. That decision made it difficult to get alternatives to be accepted. Those community groups that can gather support from political leaders and community leaders can be successful.

Alex: Are there any issues that you thought the department of sanitation was ignoring by deciding to build the garage in a growing, transitional, residential community of Hudson Square Park?

Mr. Pietrantone :They did not take into account changing demographics and did not consider the fact that the neighborhood became residential .

Alex:Can you elaborate on the contract that you had with the city regarding the movement of the garage to Hudson Square and the lawsuit that you filed against the city move the garage from Gansevoort Peninsula under the Hudson River Park Act? Can you explain little about the act?

Mr. Pietrantone : The contract was about vacating land for the park and outlined a schedule for movement of garage. If the city did not comply, it would face monetary penalties . The city was using park land. The Friends of Hudson River determined what actions would be taken to move facility, and what fees should be charged for late movement.

Alex:Do you think an alternative will be implemented for the Hudson Garage?

Mr. Pietrantone :No alternative will be implemented. This is because the city does not want to abandon its investment. The appeals from the community lost. Construction will continue until completion.

Alex:According to the former Commissioner of Department of Sanitation named Norman Steisel who came to talk to our class, industrial facilities are built in industrial areas, there is really no shortage of land in NYC and truck facilities can have a big impact. Yet, why do you think that the garage is being built in a residential community?

Mr. Pietrantone : At the time the site was chosen, it was suitable because it is in close proximity to the highway. When you factor people that moved to live there, you realize that the community was not considered. An alternative is spreading out smaller garages, and this is what the community advocated to lessen impact on environment and community

Alex:Why did the city not agree?

Mr. Pietrantone :It is hard to reverse decisions in the city. Money has been spent. There are political ramification. No body wants to admit to making the wrong decisions.

Alex:There has been a lot of celebrity involvement against the building of the garage and a lot of influential players were involved, yet the community was not successful. Why?

Mr. Pietrantone :You have to take advantage of opportunities. If this came earlier, support base was created, if the reactionary movement was created earlier, before the plan, there would be a different outcome.

Alex:How does the sanitation garage relate to nimbyism?

Mr. Pietrantone :This is not the typical NIMBY issue because the people advocated alternatives, so it’s not like they wanted nothing to be built at all.

Alex:Is the movement of garage from the Gansevoort Peninsula a NIMBY issue?

Mr. Pietrantone :No, because a garage is incompatible with park space. There is an issue of public safety and public risk.

Alex:What is the most important environmental impact that sanitation trucks have?

Mr. Pietrantone :They have an impact on air quality and take up space. The Hudson River Park was created to provide open space.

The Friends of Hudson River Park(FOHRP) is a nonprofit organization that advocate for a Hudson River Park. This organization filed a lawsuit against the city to move a sanitation garage from the Gansevoort Peninsula under the Hudson River Park Act and thus played an important role in the controversy surrounding the Hudson Square garage. Through this interview, I learned interesting information about the issues surrounding the garage, such as that FOHRP proposed to extend their deadline for movement of the garage from Gansevoort Peninsula if they city could come up with alternatives. The FOHRP understood the big impact that the garage would have on the residential community and did not want to choose between one community or another. However, it is the city who did not want to accept alternatives, and probably due to fear of political ramifications that might result from reversing its decision, decided to go on with their plan despite the impact the garage would have on the community. A lot of money was involved, and once the project begun, it had to be completed. Thus, through this interview, I learned that the garage will almost surely be completed; the community has lost.

Mr. Pietrantone has sent me that that have information about the case related to the movement of the garage, the Hudson River Park Act that mandated the relocation of the garage from Gansevoort Peninsula and Mr. Pietrantone’s testimony in which he asks the city to reconsider the location of the garage in Hudson Square because of the impact such a facility would have on the community. He states, “We understand the community concerns about the size and scope of the proposed garage and concentration of Districts, and these concerns should be given their due consideration – just as the freeing up of Gansevoort demands. Furthermore, if the Council, or the Department of Sanitation can identify a change in the current proposal for either the size of the garage or location of the salt pile that would allay those community concerns, and result in a better solution for the City overall but would delay the vacating of Gansevoort, we would not object, provided there was no further infringement of the Hudson River Park Act.” Thus, Mr. Pietrantone urges the city to consider an alterative to the Hudson Square Garage in order to lessen the negative effects that the sanitation truck garage would have on a nearby residential community in terms of health, residential growth and impact on the environment. Mr. Pietrantone states that he is willing to not impose monetary penalties and delay the process of moving the garage from Gansevoort Peninsula to Hudson Square if the city and community can come up with alternatives. Yet, even though the community proposed many alternatives, none were accepted. Only the city officials can answer the questions as to why.

The FOHRP are involved with community organizations and advocate for public space. The lawsuit that was filed against the city that stimulated the building of the Hudson Square Garage was due to advocacy for the community and public space. Additionally, the FOHRP partner with many environmental organizations that seek to protect and preserve the environment. Thus, the FOHRP have always represented the community, and strived to protect the environment. It was thus no surprise that the nonprofit organization proposed to extend deadline for moving the garage from Gansevoort Peninsula because they did not want to choose one community over the other.

Friends of Hudson River Park Testimony

Energy Use

The sanitation garage in Hudson Square would produce an increase in heating, lighting and ventilation energy consumption compared to energy consumption of three separate sanitation garages in districts 1, 2 and 5(4). However, the facility will not significantly impact energy supply and no detailed analysis was carried out on the issue of energy use(4).

An energy savings plan would be implemented in the Hudson Square Sanitation garage. For example, “as an energy saving feature, sensors would be used to detect buildup of carbon monoxide and trigger the HVAC system to supply fresh air and exhaust air from the garage areas as needed(4).” The salt shed would be used for storage and thus no energy would be spent on cooling and heating, and very little energy would be spent on intermittent lighting. The garage facility would use low mercury, energy efficient fluorescent light bulbs and will maximally use daylight to save energy for lighting the facility. The trucks would derive energy for operation from diesel fuel. B5 Biodiesel would be utilized, with 5 percent of it being of renewable origin(4).

Projection of Hudson Square Garage (19)

Construction Impacts

Construction impacts are considered to include “temporary,” yet “disruptive and noticeable affects” on an area on which construction is being performed. The garage site, currently owned and used by the United Postal Service (UPS) for the parking and staging of trucks, would be used as the garage location. The salt shed would involve the demolishing of Manhattan District 1 (MN1) garage. (5).

The project is not expected to involve an “unusually lengthy construction period” (5). Construction is planned to last approximately three years, both sites included; it began in 2009 and is set to end sometime in 2012. The garage and salt shed design was planned to last 18 months. Demolition was planned to take 8 months; shop preparation for construction, 6 months; and “mobilization” construction for the sites, 6 months.

The biggest form of construction impact thus far seems to be noise and physical impact, which are set to last three years. Physical disturbance includes limited excavating, pile driving, and the pouring and completion of the first parking level slab within the garage. Construction is also set to operate between the hours of 7 am and 4:30 p.m., but no traffic-related increases are supposed to occur to the point of any measurable disadvantage (5).

Along with site construction there is the possibility of “localized construction dewatering,” which would involve removing, analyzing, and discharging any found water in the construction area into the city sewer system for treatment at the Newtown Creek WPCP. There also might be some sidewalk enclosures and detours during the construction process (5).

In relation to historical locations, or national historical landmarks (NHL), construction would take place near two NHL: the Holland Tunnel Ventilation Building and the James Brown House. Though the James Brown House was monitored during construction of the nearby Urban Glass House for weakening or damaging of infrastructure, no damage is expected to occur during the building of the Sanitation Garage (5).

The two “open spaces” nearest the construction sight are Canal Park and Hudson Square Park, but access would not be limited to the areas during construction. Dust control is expected to be limited following procedure. Noise levels on the Canal St. and West St./Route 9A areas, which are arterialist and through-truck routes) have higher noise levels than “Noise Exposure Guidelines for Outdoor Areas and Residencies” of the CEQR recommends, but supposed implementation of a Noise Mitigation Plan should reduce any noise added; no extra precautions have been taken (5).

Natural Resources

“Natural resources” are considered to be existing natural resources on site and in adjacent areas, including plants and animals that are capable of adding to New York’s environmental habitats. However, construction is taking place in a highly urbanized area. Wetlands and surface water are not in the area of construction. The construction of both the garage and salt shed is being built in a floodplain, Flood Zone A5 (EL10), and located 350 ft. east of the Hudson River. Construction in a flood plain is related to the 1988 New York City law, “Local Law 33,” stating that construction in a floodplain requires the lowest base level of an inhabitable building to be at least one foot above base flood level. The MN1/2/5 Garage is not being built as a residential building, however, and seems to be exempt from this requirement. The garage and salt shed would also have floodgates. (6)

To offset natural resource impact, the garage will contain a “green roof,” of vegetation and approximately 17 “street trees” will be added to the area (6).

Public Health

Public health includes “the activities that a society carries out in order [to] create and maintain an environment in which people can be healthy.”(7) This involves air quality, hazardous materials, construction, and natural resources.

Air quality and odor: Public health considers the localized increment of air emissions from mobile and stationary sources would not cause significant impact on the emissions. There has been consideration of a link between respiratory diseases and levels of nearby traffic as related to Chapter 22 of the FEIS (7). A recently proposed rulemaking (72 Federal Register 54112, Sept. 21, 2007) suggested that “25 HDDVs meeting USEPA 2007 model year standards for particulate matter” (7) to streets would be considered significantly related to public health. However, the trucks that DSNY plans to use are ten times cleaner than1998-2004 model year trucks, 25 times cleaner than1991 – 1997 trucks and 60 times cleaner than 1984-1990 model year trucks. The trucks will also use clean diesel technology. (7)

Concerns about odor are slight. Waste mater and recyclable material may be held in the garage for a maximum of 8 hours, and involve a maximum of 25 trucks; the trucks shall be closed. This may contribute to an occasional odor, but this limit has been set (and originally was set at 12 trucks, and then increased to 25). A vermin control plan shall be implemented. (7)

While no hazardous material shall be included in storage or in the building of this project, there was found to be asbestos-like substance in the ceiling pipes of the MN1 garage that was torn down in preparation for the salt shed. (7)

Garbage trucks parked around Hudson Square site.

Solid Waste

In New York City, DSNY is responsible for the collection and disposal of waste and recycling from residences, some non-profit institutions, tax-exempt properties and City agencies. DSNY also collects waste from street litter baskets, street-sweeping operations and lot cleaning activities. Although a specific study was not done for the waste management in the area surrounding Hudson Square Park, an executive summary of NYC waste was put together(8) According to the study, in NYC 16,076 tons of waste is managed daily, by way of 2,024 vehicles. In the area closest to Hudson Square Park, although still relatively far from it, West 59th street, daily averages are about 1,068 tons of waste managed by 124 vehicles. This figure represents the least am mount of vehicles managing a fairly standard amount of waste, perhaps due in part to the lack of storage facilities for sanitation vehicles in Manhattan.

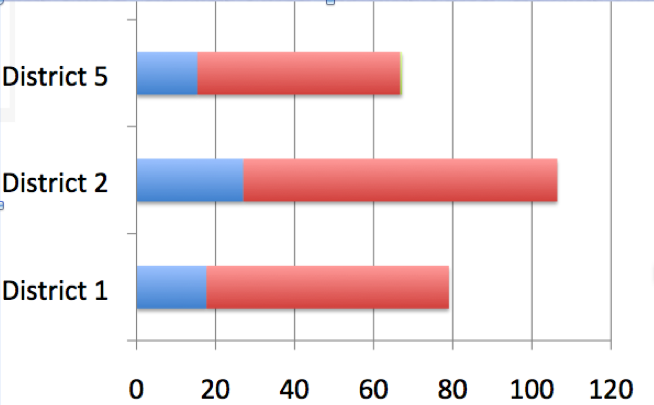

The Monthly Report on NYC Curbside Municipal Refuse and Recycling for July 2011 provides statistics on waste management in Manhattan’s 12 districts as well as capture and diversion rates(9). In Manhattan’s second district, encompassing the West side between Canal and 14th streets, 9.7 tons of metal, glass and plastic recycling are collected per day. 15.3 tons of paper recycling are collected daily in the area, as well at 79.4 tons of refuse. These figures, along with those of the districts 1 and 5 (also to be served by the Hudson Square Facility) represent about a fourth of the waste for collection in Manhattan. The capture rate for the area, or the percentage of garbage collected in terms of the total amount of garbage they propose was designated for removal. In District 2 there is a capture rate of 46.6%, the second highest percentage in Manhattan. This brings into question the need for a new garbage facility, as the methods currently being conducted in the first two districts of Manhattan constitute the two highest rates. The diversion rate reflects the amount of material that needs to be transferred from waste into recycling after pickup. The diversion rate for District 2 is 23.9%, the second highest in Manhattan. What this means is that members of the district surrounding Hudson Square are the least accurate in sorting recyclables from their waste. The implication of this figure is that perhaps the resistance in this case of NIMBYism surrounding the placement of the Hudson Square garbage facility has more to do with an upwardly mobile attitude of a recently thriving neighborhood, and less to do with the environmental factors implicated by the facility. It seems that, in terms of actively helping the environment by recycling, the community surrounding Hudson Square is lacking. (9)

Waste Statistics (9)

TOTAL WASTE IN TONS: 192

TOTAL RECYCLING IN TONS: 68

The Environmental Impact Statement for Sanitation Garages and Salt Sheds in Manhattan provides information on the standards and restrictions on building facilities related to the plan for Hudson Square(10).

According to the CEQR Technical Manual, actions involving new construction or other development generally do not require a detailed evaluation of solid waste impacts unless they are unusually large. Under these pretenses, the Hudson Square Facility doesn’t require a detailed evaluation. The general belief on the construction of a new waste facility is that it would not increase the volume of solid waste generated by the three district garages; rather there would be a shift in the location of waste generation. In terms of solid waste the garbage facility would have a minimal negative impact on the environment. In terms of evaluating the amount of waste that the new facility would generate, we can look to figures on other garages in the immediate area such as the Garages as Gansevoort/Pier 52 and a Garage in district 5. Most of the waste generated here comes from about 1400 employees. The peak volume of waste daily is estimated to be approximately 1422 pounds. The new facility would be projected to generate about the same, and would not “materially increase the generation of waste”. In other words the waste produced by the facility would be low enough as to be manageable and removed. Another important estimation is the amount of travel time in the collection of solid wastes, which with the addition of a new facility would be decreased because there would be a shorter distance to get to a garage in lower Manhattan. However they propose that there would be little to no effect on the amount of travel time for recycling trucks. This waste generation would also have minimal impact on the environment, generating less or the same amount of waste found acceptable in the garages in the surrounding districts. The reduced time spent collecting solid wastes resulting from the addition of a facility between the two existing ones would allow for higher speeds and fewer stops, as well as eliminating the need for relay stops. In terms of environmental impact, this would reduce the amount of pollution from the burning of gas, although exact figures aren’t given. (10)

Hudson Square Community

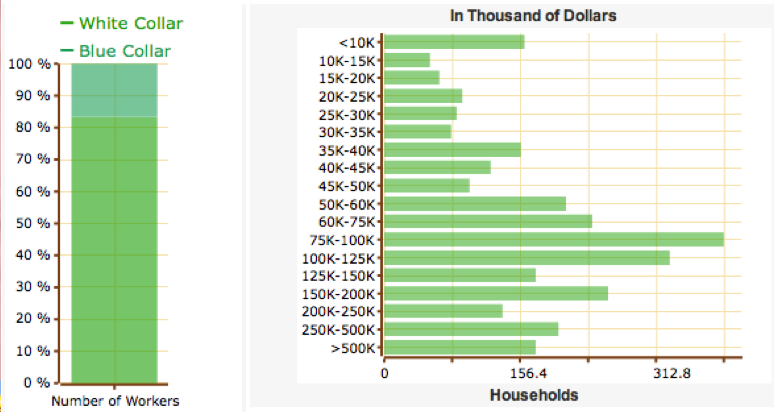

Hudson Square Residential Income (20)

Development

One of the most highly-publicized concerns about the facility’s construction was how it would affect the neighborhood’s rising affluence and development. Hudson Square, formerly the Printing District, is primarily funded by Trinity Real Estate who own about 40% of the real estate (11). In the late 1980s and 90s the neighborhood’s primary industry, printing, was in decline because of changing technology and the implementation of digital publishing. Through the nineties Trinity worked to improve the community with luxury residential buildings, and the south end of Hudson Square was rezoned in 2003 to allow residential use (12). New buildings, restaurants, and businesses began to pop up after the rezoning and residential occupancy grew to four percent (13). Trinity continues to try to foster growth in the neighborhood, recently announcing a proposal for yet another rezoning allowing for up to 3,500 new residential apartments (14), increasing residential occupancy to twenty-five percent (13).

In light of the community’s rising status, many are concerned that the construction of the sanitation garage is a step backwards. In 2007 when the plans for the facility were announced it sparked outrage. Locals were not pleased to learn of the proposed 400-foot radius around the site, a large chunk of real estate for the small community. Worries also arose that traffic would increase in the already crowded streets around the Holland Tunnel (15). In general, many residents saw the plans unfair and counterproductive.

Polling the Community

Friends of Hudson Square raised many concerns with the proposed Hudson Square Facility. The group noted the exhaust pollution from vehicle trips, and airborne salt as their major issues with the building(16). LCA reports show that the community’s general environmental impact is negligible, so these concerns are largely unfounded. In an attempt to find the real issues that have caused such a vocal community backlash against the development of the garage we polled 30 Hudson Square residents. Of the 30, twenty-seven said they were decidedly against the facility. The most prevalent concern residents raised was its location next to the scenic Hudson River, believing the facility will be an eye-sore. Fourteen believed it would cause an excessive amount of traffic. Eight told us they were worried about the smell, which is a pretty irrelevant concern considering that the construction site is currently surrounded by un-concealed trucks and the new facility will house mostly empty vehicles. Only five people reported being worried the facility would increase pollution, and fourteen believed it would cause an excessive amount of traffic. It appears that the community’s main concerns with the facility are not environmental but in how the facility will affect their day-to-day lives. This is a textbook example of NIMBYism; a community being opposed to a new development simply because it’s their neighborhood.

Flier for Hudson Rise by Friends of Hudson Square (16)

HUDSON RISE &

COMMUNITY COURT INVOLVEMENT

In 2005, Friends of Hudson Park, an organization founded in 1998 that supports the park and works to sustain it, filed a lawsuit against the Department of Sanitation (DSNY) to stop construction of a garage on the Gansevoort Peninsula that was started in January of 2005. Friends also demanded that all sanitation operations from the 8-acre landfill on the Village waterfront cease and be removed. The suit charged the DSNY with violating a 1998 agreement called the “1998 Hudson River Park Act” that created the 5-mile long park along the waterfront, which runs from 57 Street to Chambers St. because that agreement included stopping use of the peninsula to park garbage trucks along Gansevoort Street. The two plaintiffs of the case asides from Friends of Hudson River Park were two community-based advocacy groups targeting the Hudson River Park Trust, the state/city agency building the park. The suit declared that the city failed to comply with the Park Act by December 31, 2003, which involved moving an old garbage incinerator and the pile of snow salt that the DSNY also stored there. The plans were then announced to build a garage on Spring Street and the State’s Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) approved it in 2006.

In 2009, Canal West Coalition, neighborhood businesses, Coop & Condo Boards, and individuals filed a class action suit against New York City under the name “Tribeca Community Association” (TCA). This class action led to the Friends of Hudson River Park joining the TCA (16). The class action suit was to block the project because the plaintiffs claimed that other sites had not been properly considered and “consolidating three districts’ garages into one large garage violates the City Charter’s Fair Share Criteria” (21). The lawsuit was dismissed in January 2010 and the part of the suit that challenged the 2005 settlement with Friends of Hudson River Park involving a timetable to get the DSNY garage off of Gansevoort Peninsula and Pier 97 (22).

Several of the plaintiffs of the 2009 lawsuit were from the Hudson Square Sanitation Steering Committee, a group that had previously opposed the SoHo Sanitation garage. The Committee was responsible for issuing an alternative plan to the Sanitation Garage 1/2/5 on Spring Street. Its features were a 2-district, rather than 3-district, station, and a shorter building height of 75 feet. Celebrities such as Kirsten Dunst, John Slattery, Michael Stipe, James Gandolfini, and Lou Reed got behind the Hudson Rise, signing a petition and attending a protest (23). A rally held on March 25, 2009 to benefit the Hudson Rise plan gathered lots of celebrity support. The celebrity support struck an odd juxtaposition with the usual environmental plans of NIMBY because people being targeted for sanitation garage-building are not often A-list celebrities, nor does this usually fit into the picture of “environmental justice.” (24).

In February 2010, the DSNY put out a bid to contractors for the original planning of the 3-district garage, expected to cost $385 million. The Hudson Rise plan was never adopted.

Conclusion

Hudson Square Sanitation garage will have an impact on the environment and on the community. Even through a facility may produce pollutants such as non-criteria pollutants, particulate matter and nitrogen oxide, as well as solid waste, the production of this matter will not be severe enough to irreversibly or significantly impact the health or the environment. Thus, it can be generalized that while many industrial facilities can produce a small negative effect on environment or health, it is an accepted occurrence in an industrial city of New York. This is so because stringent laws are established that protect the environment and public health. Thus, as long as no laws are violated, as has been proven by the DSNY for the Hudson Square Garage, industrial facilities may be constructed because they are necessary for successful functioning of a technologically driven, industrial city of New York. Technology in New York city is necessary for the city to continue to thrive and be effective, and it is the role of science to ensure that this technology does not impact the environment or public health to a significant amount, so that the city may continue to develop, grow and improve through facilities such as sanitation garages. The issues surrounding the facility and its impact display the importance of the connection between science and technology in New York City .

The impact on the community by such the Hudson Square Garage is complicated, and it is hard to prove that a facility such as the sanitation garage will or will not have a significant impact on its character. The Hudson Square community thought the facility would have a negative impact because it would produce traffic, noise, and interfere with the transition of the area into a residential region. According to the Executive Director of a nonprofit organization Friends of Hudson River Park, the construction of the facility would be damaging and inconsiderate due to the changing demographics of the area. This is why he even proposed to extend the deadline for the moving of the garage because he did not want to choose one community over the other. The DSNY stated that the sanitation garage would not have an important enough impact on the community’s character, without backing this claim(17). Constrained by financial issues, the city went on to build the garage in the location it intended to before the area became residential(17). The sanitation garage would ultimately serve the public good, even though residents of the Hudson Square area do not believe that this is entirely the case.

According to a reliable source with extensive knowledge of the department of sanitation who will not be named, New York City is very dense and it is difficult to find alterative locations for a sanitation facility. The Department of Sanitation tries to find a lulu, least-undesirable-land-use, a place that will satisfy its needs and will not impact a community too dramatically. The Department of Sanitation attempts work with the community to produce a plan that will address its concerns. However, a compromise that address all concerns raised by community and all needs of the city is not always possible. The Sanitation Department prefers to have a single location for its truck facility because this allows it to control personnel and equipment more effectively. Additionally, operating at many facilities increases capital costs and operating expenses.

All this has proven to be the case for Hudson Square Sanitation Garage. The city had attempted to find compromise with the community by answering its questions about the project and has even made some concessions, such as equipping trucks with Clean Diesel Technology. Nevertheless, all the community concerns were not met. This is largely because it would be more cost effective for the city to operate the facility in one location since acquiring land in other Manhattan areas is expensive. It can be concluded that the issues of expense, location, impact on community and environment surrounding the garage are likely to face many such facilities throughout New York and the United States.

———————————————————-

Sources

1. Doherty, John. “Final Scoping Coument Draft of Environmental Statement.” Department of Sanitation. June-July 2007. Web. 15 Nov . 2011. <http://www.nyc.gov/html/dsny/downloads/pdf/garages/finalscope12n5.pdf>.

2. “Air Quality.” Department of Sanitation. Department of Sanitation, Web. 2 Nov 2011. <http://home2.nyc.gov/html/dsny/downloads/pdf/swmp_implement/mts/M125_DEIS/Chapter_19.pdf>.

3. World Health Organization. “Health In The Green Economy.” World Health Organizaton. World Health Organization, 2010-11. Web. 2 Dec 2011. <http://www.who.int/hia/hgebrief_transp.pdf>.

4. “Energy.” Department of Sanitation. Department of Sanitation, 2008. Web. 5 Dec 2011. <http://www.nyc.gov/html/dsny/downloads/pdf/swmp_implement/mts/M125_FEIS/C16.pdf>

5. “Construction Impacts.” Department of Sanitation. Department of Sanitation, 2008. Web. 5 Dec 2011. <http://www.nyc.gov/html/dsny/downloads/pdf/swmp_implement/mts/M125_FEIS/C21.pdf>

6. “Natural Resources.” Department of Sanitation. Department of Sanitation. Web. 5 Dec 2011. <http://www.nyc.gov/html/dsny/downloads/pdf/swmp_implement/mts/M125_FEIS/C11.pdf>

7. “Public Health.” Department of Sanitation. Department of Sanitation, Web. 5 Dec 2011. <hhttp://www.nyc.gov/html/dsny/downloads/pdf/swmp_implement/mts/M125_FEIS/C22.pdf>

12. “Executuve Summary.” Hudson Square Rezoning. Department of Planning, 2003. Web 15 Dec 2011. <http://www.nyc.gov/html/dcp/html/pub/hudsonsq.shtml>

13. Arak, Joey. “Hudson Square Transformation Includes New SHoP-Designed Tower.” Curbed. Curbed, 11 Feb 2011. Web. 15 Dec 2011 <http://ny.curbed.com/archives/2011/02/11/hudson_square_transformation_includes_new_shopdesigned_tower.php>

14.Anderson, Lincoln. “Trinity says it’s time for residential in Hudson Square.” The Villager. The Villager, Feb 2007. Web 15 Dec 2011. <http://thevillager.com/villager_407/trinitysays.html>

21. PlanNYC, . “SoHo Sanitation Garage.” PlanNYC. NYU, 6/7/2011. Web. 16 Dec 2011. <http://www.planyc.org/taxonomy/term/742>.

22. Amateau, Albert. “Judge dumps Hudson Square mega-garbage garage suit.” Villager. 20 Jan 2010: n. page. Web. 16 Dec. 2011. < http://www.thevillager.com/villager_351/judgedumps.html>.

23. “Celebrities Must Put Up With Sanitation Garage In TriBeCa.” The Huffington Post. The Huffington Post, 6/16/2011. Web. 16 Dec 2011. <http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/04/16/celebrities-must-put-up-w_n_849692.html>.

24. Amateau, Albert. “Stars Add Glitz.” Villager. 25 Mar 2009: n. page. Web. 16 Dec. 2011. <. http://www.thevillager.com/villager_308/starsaddglitz.html>.

One Response to Hudson Square Sanitation Garage