Justice Sotomayor on Digital Surveillance, 3rd Parties, and Societal Expectations of Privacy in Public

In United States v. Jones the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously ruled that attaching a Global Positioning System (GPS) device to a vehicle for the purpose of location-tracking constitutes a search under the Fourth Amendment. More notable than the unanimity of this decision, is that the majority opinion was premised on the fact that the federal government physically trespassed on Antoine Jones’ private property (his car) in order to install the GPS — leaving open the question of whether such surveillance would have been legal had the government not physically installed a tracking device. To this end, United States v. Jones raises more questions than it answers regarding the legality (and morality) of surveillance in everyday information environments. Governments, corporations, and individuals do not need to physically enter your house, your desk, or tap your phone line, to gain access to the multitude of personal information that flows through your everyday environment, and beyond.

In separate concurring opinions, Justice Alito and Justice Sotomayor both problematize the majority opinion’s focus on “physical intrusion,” yet only Sotomayor’s concurring opinion offers a consideration of the interests and concerns of U.S. citizens who currently exist in what is, at least to them, a largely mystified and little understood information environment. As Sotomayor argues in her concurring opinion:

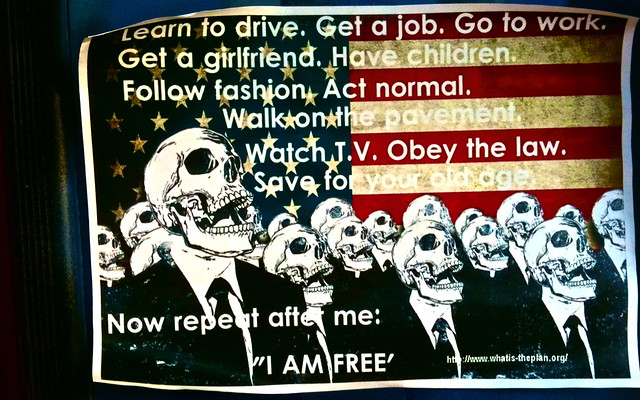

Awareness that the Government may be watching chills associational and expressive freedoms. And the Government’s unrestrained power to assemble data that reveal private aspects of identity is susceptible to abuse. The net result is that GPS monitoring—by making available at a relatively low cost such a substantial quantum of intimate information about any person whom the Government, in its unfettered discretion, chooses to track—may “alter the relationship between citizen and government in a way that is inimical to democratic society.”

I would take these attributes of GPS monitoring into account when considering the existence of a reasonable societal expectation of privacy in the sum of one’s public movements. I would ask whether people reasonably expect that their movements will be recorded and aggregated in a manner that enables the Government to ascertain, more or less at will, their political and religious beliefs, sexual habits, and so on.

Sotomayor’s focus on “a reasonable societal expectation of privacy in the sum of one’s public movements” is important as it’s quite clear that society is not aware of the extent to which they’re being tracked, nor is there a social consensus on what constitutes ‘being in public.’ In my own research I’ve consistently found that when young people learn about the most basic ways that their personal information is being aggregated, they begin to articulate more sophisticated privacy concerns alongside a general amazement that such surveillance is actually happening — legally — in what they think of as private places: their facebook profile, their email, their texts, and so on.

Sotomayor concludes this point by arguing that society expects more privacy than it currently has in the digital age, and calls for a decoupling of secrecy and privacy in order to develop more situated and accurate judicial understandings of when and where people expect privacy:

More fundamentally, it may be necessary to reconsider the premise that an individual has no reasonable expectation of privacy in information voluntarily disclosed to third parties … This approach is ill suited to the digital age, in which people reveal a great deal of information about themselves to third parties in the course of carrying out mundane tasks. People disclose the phone numbers that they dial or text to their cellular providers; the URLs that they visit and the e-mail addresses with which they correspond to their Internet service providers; and the books, groceries, and medications they purchase to online retailers. Perhaps, as Justice Alito notes, some people may find the “tradeoff” of privacy for convenience “worthwhile,” or come to accept this “diminution of privacy” as “inevitable,” and perhaps not. I for one doubt that people would accept without complaint the warrantless disclosure to the Government of a list of every Web site they had visited in the last week, or month, or year. But whatever the societal expectations, they can attain constitutionally protected status only if our Fourth Amendment jurisprudence ceases to treat secrecy as a prerequisite for privacy. I would not assume that all information voluntarily disclosed to some member of the public for a limited purpose is, for that reason alone, disentitled to Fourth Amendment protection.