Work

From The Peopling of New York City

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| ||||

Work has had a prevalent effect on the lives of immigrants throughout their history. As one of the most cited reasons for immigration, work's effects can be felt in all other aspects of immigrant life, especially here in New York City. This is especially true in regards to three of the more prevalent themes (Racism, Politics and Ghettos and Enclaves) found in the lives of all immigrants both here and in the nation as a whole.

Contents |

Work and Racism

Throughout New York City’s history, racism and work have affected one another. Work has served as a means by which the barriers of race have been broken, but in many instances, it has served as a vehicle for culturing and maintaining racism. Work has provided a platform for bringing different races together and teaching tolerance. However, strangers can not only use a person’s job to judge their race, but also use their race to judge what type of work they may be capable of doing. New York presents an interesting and rare challenge to its inhabitants because it is the “melting pot” and brings so many different races in close proximity. People of New York are faced with the task of balancing their heritage with their willingness to embrace the diversity around them. Racism is a mindset and lifestyle that does not need to be learned through years of education and is not created, at least in most cases, by the victim. Therefore, it plays a central role in the everyday lives of the people of New York.

Work breaks down racism by allowing people of different races to prove their worth and set the example for other individuals of the same race. Individuals who have the strength and willpower to break through barriers show everyone that “it can be done;” therefore, this changes the view of that race by all people. Sports provide numerous examples that many people would be familiar with, including Arthur Ashe and Jackie Robinson, because athletics, along with the arts, are centered around judging people on individual merit rather than race. However, white-collar workers also earn respect for their race – people will respect a doctor for the dedication required for doing that job and for the service the job provides, regardless of the race of the doctor. Additionally, schools give the staff and the students the opportunity to witness the skills and strengths of different races and learn about the traditions in a neutral setting. This provides people with the chance to develop respect for all races and learn to judge individuals based solely on merit.

Unfortunately, the workplace also provides numerous opportunities for reinforcing racism. People who own businesses can preferentially hire workers from their racial background. This can lead to certain types of jobs being dominated by a particular race. Several examples exist in New York, including the garment district that was dominated by Jewish people at the turn of the 19th century, who then helped other Jews find jobs, the docks and ports being dominated by Europeans, or Jamaican women creating a third of the health care workforce (Vickerman, 204). Certain jobs are also stereotypically associated with particular races, making individuals of other races less willing to choose that career. New immigrants from minority races experience more racism and resistance than other immigrants, which forces them to accept low-paying jobs. Their lack of establishment robs these minorities of the power required to unionize and demand fair working conditions. Education also plays a major role, where race or dialect contributes to the types of jobs an individual can apply for. The ability to speak without an accent allows an individual to advance more quickly. Having money, which applies to well-established families, allows individuals the comfort of education and better jobs, a luxury not enjoyed by immigrants who need all members to work to help support the family. People will try to find work with others of their race, because they may feel more comfortable and accepted in that setting, even if it means a longer commute.

The question people have to consider is whether the workplace serves as a platform of integration or a platform for reinforcing racist tendencies. If people are more concerned with being comfortable, then the workplace allows the continuation of racism. Only when people are willing to challenges themselves and pursue careers without regards to the type of people currently doing the job, will the racist tendencies recede and, hopefully, become extinct.

Work and Politics

The effects of work on politics (and vice-versa) have been prevalent throughout New York City's History. During the height of power for New York's Labor Unions, specifically the post-World War II era, nearly every vocation involving labor: manufacturing, service, and even managerial occupations, was represented by some type of labor union or equivalent social institution. The organizational structure and militant solidarity found in those unions enabled them to act as springboards for political activism. Nowhere was this more obvious than in the struggles immigrant groups have had to deal with over the decades in order to organize as a working class and gain a powerful voice in deciding the city's economic and political policies.

Labor’s Effects on Politics

The effects work and politics have had on each other can be seen as early as the 1920's, during the influx of the first great immigrant wave, characterized by the overwhelming representation of Italians and Eastern European Jews. Into this changing, industrialized economy, most of these immigrants brought nothing more than the strength of their limbs, as they, for the most part, lacked any of the special skills necessary for work in a trade. In addition, an even fewer proportion of them had the training to enter the professional workforce. These circumstances inevitably led these immigrants to find jobs in labor, under ofttimes extreme, unfair and dangerous conditions. These same conditions would eventually lead these immigrants, as well as other working-class laborers, to band together and begin joining and/or forming unions. According to Joshua Freeman these unions would take center stage as the channel by which the working class would influence American society, helping to eventually democratize the country (40).

Inevitably, Labor Unions would begin to address their members' concerns via litigation and political mobilization. During the post-World War II era the New York labor movement reached the height of its political power. Due to feelings of anti-fascism, the Left gained a high level of prominence in the labor movement’s sociopolitical ideologies. This in turn led to a very socialist atmosphere, along the lines of many European cities and townships. Effectively, for a time, New York became America’s one great socialist experiment (Freeman 55). This is not to say that New York was removed from the larger American society as a whole, with its distrust of anything communist. In fact, one of the major sticking points between the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) and its mother-organization, the American Labor Party (ALP), was the former’s willingness to adopt many socialist ideologies and the latter’s counter-willingness to remove itself from the stigmas associated with the word “communist.” Whether this played a part in the schism between the two groups is a matter for debate, but what is certain is that it delayed joint-action from the two labor organizations for a much longer time than should have been necessary.

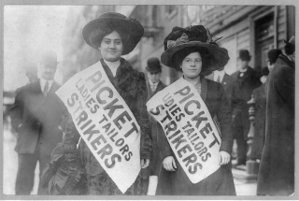

Regardless, the Labor-left allowed for a wide array of civil reforms to gain support and strength in New York City. The International Ladies Garment Worker Union, one of the City's and the Nation’s largest associations, would pave the way for feminine representation in New York’s political sphere. More importantly for immigrant groups, however, the ILGWU would also provide an outlet for ethnic representation in the labor movement as a whole. Beginning specifically with the Chinese, whose own attempts at unionization had been stifled by racism and discrimination, the ILGWU would prove a willing and able participant in their organization, as well as that of other ethnic groups.

Before the 1960’s, New York’s Chinatown was in no way a union-friendly place. An underground economy and deep mistrust of outsider organizations convinced the Chinese that labor unions were ineffective and emotionally removed from their own problems. This mindset convinced those same outsiders that the Chinese were heavily internalized and withdrawn from the rest of society, a perception which caused them to view the Chinese’s problems as purely an ethnically internal one and led to general disinterest in aiding them. Peter Kwong described the situation in a nutshell:

“Workers in the Chinese community have no effective organization to represent them, nor a leader to champion their interests. Even federal and state authorities are not troubled by widespread violations of minimum-wage laws in Chinatown. The Department of Labor won’t take any action unless the Chinese complain, and the workers cannot complain for fear of retaliation (140).”

Effectively, the Chinese were stuck in a vicious cycle from which it seemed there was little they could do to escape. The ILGWU would provide that means of escape. Unlike the other labor unions, the ILGWU recognized the strength and sheer manpower available to a Union that had organized the Chinese. During the course of the garment industry’s development here in New York, factory owners and manufacturers of women’s apparel had moved their operations into Chinatown, due in large part to lower building costs and the abundance of cheap labor available. Starting in 1950’s, the ILGWU began attempts to organize the Chinese, and by 1974 every female garment worker in Chinatown had joined at least one of three municipal branches (Local 23-25) of the ILGWU (Kwong 147). Eventually, the ILGWU’s effective organization of Chinese women would set a precedent for the rest of the labor movement.

While it is good to showcase the positive effects labor has had on social change, it is just as important to avoid romanticizing the activism for civil liberties on the part ILGWU and the labor movement as a whole. While it is true that they supported desegregation and advocated equality in the socioeconomic sphere, in their own organization and leadership hierarchy most labor unions did little to put their egalitarian ideologies into practice. This was especially apparent when it came to women in the workforce. As Freeman points out:

“The New York labor movement had an unusually high percentage of female members, reflecting the nature of the city’s economy… Yet in spite of this strong representation, very few women unionists achieved prominence. The many obstacles they faced included greater domestic responsibilities than men, less confidence about taking part in public activities, and open hostility from male compatriots (46).”

The implications this had for female members, especially those coming from immigrant backgrounds, was a chilling portrayal of the inefficacy of an organization that refuses to apply its own ideologies on itself. For example, in Chinatown, around the 1980’s, the female members of the ILGWU met unofficially to discuss the prevalent concerns they had with the union and to criticize its leaders (who happened to be primarily male). It soon became apparent that their primary concern was the need for a children’s day-care center, as the women worked long hours, couldn’t leave their pre-school children at home, and so had to take their children with them to work in the dangerous factory environment. When they presented this appeal to the union, its president flat-out refused, declaring that child care was not the union’s primary concern and that it would set an impractical precedent among the other ethnic groups in the union, who would also desire similar day-care centers which would put a drain on the ILGWU’s resources (Kwong 157-158). Fortunately for the Chinese, they had had, by this point, much practice in militant mobilization and were able to pressure the union into acquiescing to their request. However, this outcome was the exception, not the norm, and one only possible in this case due to the fact that women had a ridiculously larger percentage of members than men in the ILGWU’s rank-and-file.

Work: The Effects of Ghettos/Enclaves

While many are hesitant to admit it, the truth is people are most comfortable around what they know, and usually uncomfortable around what they don’t. Many immigrants prove this theory by settling in ethnically-centered ghettos and enclaves upon their arrival in New York. There are positive aspects to this pattern, such as providing a way to cope with language barriers and cultural differences at first. However, the inevitable negative of this is when it prevents people from stepping outside their comfort zone, leaving little room for expansion and growth. When it comes to finding a job and making a living, these conflicting effects of ghettos and enclaves become quite apparent.

For example, living in an ethnically-centered enclave, such as Chinatown in New York City, may seem beneficial to the Chinese at first. When immigrants arrive here, they are quickly accepted and grouped together with their fellow clansmen. Often, Chinatown employers are inclined to hire mainly within their own clans, therefore finding a job in Chinatown for new immigrants is not usually very difficult. The difficulty comes when these small Chinatown businesses are forced to compete with larger, modernized, white-owned firms. Hence, the survival of most of these Chinese businesses depends on keeping costs down, and therefore wages as low as possible. Many Chinese workers are forced to endure long hours of labor for below minimum-wage pay as a result.

Because of the homogenous population that exists in an enclave like Chinatown, most of these immigrants do not speak English and will never have to learn. Therefore, they are not exposed to American laborers and the difference in their working conditions. This means many new immigrants do not know exactly just how overworked and underpaid they are in comparison. Fortunately for their employers, this prevents these immigrants from complaining or leaving their jobs. Yet sadly, even the few who do understand the injustices they endure are afraid to protest because of Chinatown culture; those who speak against their employers are fired and blacklisted, preventing them from being hired almost anywhere in Chinatown again.

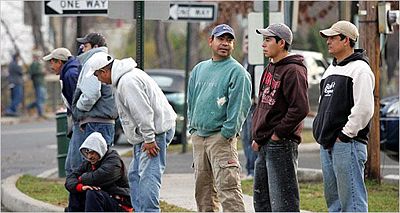

It is easy to see how collectivity and cultural-based loyalty to Chinatown economics can severely hurt many Chinese immigrants’ chances of obtaining lucrative and fair jobs. Mexican immigrants, on the other hand, face almost the exact opposite problem. Due to the lack of a single major enclave like the Chinese have, Mexican immigrants are widely dispersed throughout all of New York. While some might see this as helping them avoid entrapment problems, it unfortunately creates a whole new set of issues.

Without any large community based area where most Mexican immigrants settle, it is quite difficult for them to unite together. They don’t have the advantage of access to job opportunities or training based on their ethnicity the way the Chinese do. It is very rare that Mexicans are able to offer their new immigrants jobs because there are so few Mexican business-owners. Therefore, there is little chance of loyalty to hire Mexican workers. As a result, Mexican immigrants find work in a wide variety of places. “The fact is that such dispersion across industries and jobs has negative long-term consequences for the group’s collective advancement and development" (Foner 283). This lack of organization among Mexican immigrants makes it difficult for them to be represented and considered in the workforce, as well as in government and society too.

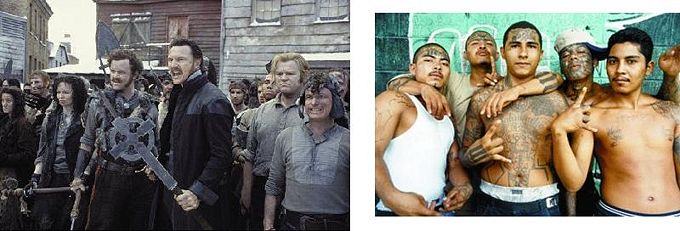

Consequentially, the lack of unity in these areas that make it hard for Mexicans to succeed legally makes other illegal options much more appealing. Mexicans are not the only immigrant group to have a large gang community though. Beginning with the Italians, Irish and Russians, and continuing still today with Blacks, Chinese, Koreans, West Indians, and Hispanics as well, gangs have played a major role in enclave societies. Unfortunately, gangs will always be relevant in these areas because they provide a seemingly “easy way out.” As opposed to most jobs, they don’t require any education, they don’t discriminate against race or language, and they can result in large amounts of quick money for those who participate. When the richest people in your neighborhood are gang members, as seen in Down These Mean Streets, the idea of becoming one is much more tempting. It is a common dilemma for those living in ghettos and enclaves to have to decide between working long, grueling hours for very little pay or joining a gang and perhaps extorting money to make up to thousands of dollars a day (Kwong).When looked at this way, it is understandably hard for legal, low-paying, menial work to compete.

Unfortunately, searching for a way to make money in America is often a struggle for any immigrant. It is clear that finding work and maintaining a steady income can be challenging for them, regardless of where they come from. Ghettos and enclaves can help with this problem by providing job connections, often based solely on ethnic loyalty, without the need for knowledge of English. When immigrants use this as a stepping stone into a more assimilated, successful and fulfilling career, ghettos and enclaves prove to be extremely beneficial. However, it is when the collective nature of an enclave prevents immigrants from learning about options outside of their community, causing them to miss their window of opportunity out, that we understand just how hindering and destructive ghettos and enclaves can be.

For Further Information: Times Article: Day Laborers