From The Peopling of New York City

Contents |

Descent into Hell

Hell’s Kitchen has a history deeply rooted in violence. From the 1880’s until the 1950’s, the area was dominated by street violence and gang control. The police only furthered the persisting issues by accepting bribes and on some occasions taking part in the brutality. For these reasons, among others, Hell’s Kitchen developed into a place well suited for its name, a place riddled with crime and surrounded by other equally unappealing areas to those of high economic status. For many years, Hell’s Kitchen was the poorest of slums, the lowest possible rung on Manhattan’s socioeconomic ladder, and yet incredibly has transformed into a quiet, gentrified neighborhood that may earn the occasional question…”Why is it called Hell’s Kitchen?”

What's In A Name?

Hell’s Kitchen was not always Hell’s Kitchen, and in fact no longer touts the name. However, the evolution of the neighborhood is completely paralleled by its title and possesses an interesting history indeed.

Up until the 1880’s, the area bounded from 57th on the north end to 35th on the south end between 6th avenue and the Hudson river was christened the name Great Kill after the river that flowed into the Hudson along what is now West 41st street (note: kill is the Dutch title of river and thus this is really the “Great River”).

In the 1880’s, when apartment buildings began springing up throughout Manhattan and the wave of mass immigration was pushing families up and out of the lower East Side, the area once known as Great Kill became overrun with crime and the streets filled with the cities worst. A plaque on the Hell's Kitchen Park on 47th street and 10th avenue tells of an urban legend about how Hell's Kitchen got its name. Above the ubiquitous New York City Parks' Maple Leaf logo, the story involves two police officers talking to each other on the corner. The first officer tells the other, "This place is Hell itself." The second officer then replies: "Hell's a mild climate. This is Hell's Kitchen." And so, this sparked a new era for the neighborhood, one dominated by riots, police corruption and violence, prostitution and gang rule. Around the same time, a small African American enclave developed on the North end of Hell’s kitchen in what is modern day Columbus circle, titled “San Juan Hill” after the bravery of the African American 10th regiment at San Juan Hill during the Spanish American Civil War. Simultaneously, the area between 6th and 7th avenues also assumed a new name, “The Tenderloin” and earned the reputation of being the worst section of Manhattan with its streets overrun with brothels and sexual deviance.

However, in 1959, residents and New Yorkers alike decided that the area formally known as Hell’s Kitchen needed a new name along with a new image and it was renamed “Clinton” after De Witt Clinton. The new neighborhood, while listed on maps with such a “respectable” title, still bears the marks left from its more “hellish” days. No matter how much effort is put into affirming the neighborhood as “Clinton” it seems that the name Hell’s Kitchen hangs on, despite efforts to rid the area of its wicked ways.

Disorder

Violence in Hell’s Kitchen was so common around the late 19th century that it was almost inevitable for everyone in the neighborhood to become involved. Some might attribute this general aggression to the presence of the Irish, whose reputation was rooted in a desire to drink and to fight. However, there is no conceivable reason that the Irish spurned all of the violence so inherent to the nature of Hell’s Kitchen. The first street gang to catch the public’s eye post civil war was the Nineteenth Street Gang, which later formed the Tenth Avenue gang and ultimately joined the Hell’s Kitchen Gang. Here, we see the idea of territory and turf arising to their fullest extent. The area carved out by Hudson Rail Road line and extending East to 8th Avenue was terrorized and monitored closely by the Gang. The leader of this group, Dutch Heinrich, was responsible for many of the robberies that took place during his regime and earned a reputation for being a mastermind of crime. Although the Hell’s Kitchen Gang fell apart after a battle with the Police, this was not the end of gangster rule in the area. Other groups such as the Battle Row Gang, the Gophers, the Rhodes Gang and the Gorillas all developed in Hell’s Kitchen to fight the last bit of law and order left in the community.Street violence was a tremendous factor of everyday life even for those not directly affiliated with gangs. Confrontations often ended in death and almost any deed could be bought for a price, even murder. The violence was not limited to civilians; the police force in the area often took part in using aggression to maintain some semblance of order in the area. On July 20 1899, one of the worst riots in the history of Hell’s Kitchen erupted on Tenth Avenue. Although the neighborhood had certainly been dealing with violence for years, never before had they witnessed such a racially charged and police fueled battle as this. While the police were meant to control the crowds, in the end the events had turned so greatly that the African American community, originally fearful of their White neighbors were now running toward the mobs just to escape the police brutality. The intensity and the ferocity of this event was not limited to this particular day, however the Tenth Avenue Slaughter was unique in the respect that the police were so involved with the murderous rampage that occurred.

Children

In the context of life during the post civil war, industrialization period, is a subject that has been assessed and reassessed for decades, and yet it Hell’s Kitchen it appears that the difficulties faced were intensified and multiplied. The heavy concentration of Irish and German immigrants during this time period, two groups well versed in drinking and subsequent violence, seemed to produce thousands upon thousands of homeless children living on the streets. They filled legitimate positions of “newsboy” or “match girl” but ultimately found themselves falling into the pattern of petty thievery and panhandling. While not exactly economic niches, these positions provided an alternative to rigorous factory work or gang involvement. For many young boys and girls, however, gangs provided a sense of community and belonging that was necessary to their growth. Although the influence was predominately negative, the prevalence of street gangs created normalcy in belonging to one and for many, there was simply no other means of survival. Perhaps the most disheartening about the child’s situation in Hell’s Kitchen, was the lack of aid and assistance needed to combat this social problem.

Prostitution

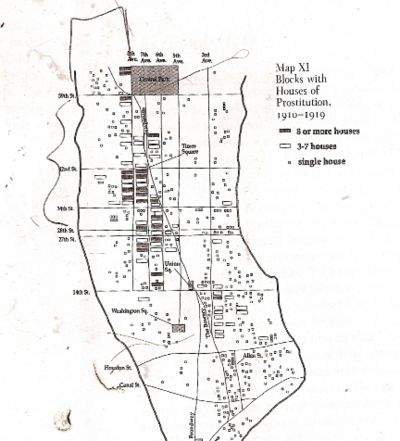

For many young women, the alternative to long factory hours was taking up residence in a brothel and making a “dishonest” living. While it would be ideal to say that Manhattan had a scarcity of these deviant institutions, they were everywhere in the period following the civil war. In The Tenderloin (the area adjacent to Hell’s Kitchen) from 1910 to 1919 there were approximately 150 Houses of prostitution in the bounds of 34th and 59th streets and 6th and 7th avenues. A visit to the area at present day would reveal one of Manhattan’s major business districts, with little to no trace of its less than admirable past. However, during this era, this sliver of Manhattan was the source of entertainment for locals and visitors alike. As the appeal of these brothels became apparent, so began the translation of many of these institutions into its neighboring Hell’s Kitchen. The transformation of street life that occurred with the introduction of these houses is noteworthy. In fact, Adam Clayton Powell Sr. once christened the area between Ninth and Tenth avenues on W. 40th Street was the “most notorious red-light district” in Manhattan and in greater New York City. Prostitutes were constantly on the streets, walking amongst children, the elderly, police, and priests. In San Juan Hill, the rise of prostitution was just as intense. And yet, Hell’s Kitchen’s development into a full-blown sex district was not only the process of gaining streetwalkers, but also the sheer number of high-class brothels that were founded. Some places had extremely high standards and peculiar requirements for customers such as ordering particular drinks or having an invitation. These higher-level houses offered the upper and middle classes exclusivity and provided extremely profitably business for the madams in charge. This sex driven culture would eventually be condemned and restricted, but at the turn of the century, Hell’s Kitchen and its neighbor the Tenderloin could easily have been the prime sex districts of the City.

References

- Gilfoyle, Timothy J. City of Eros. Norton, 1992.

- O'Connor, Richard. Hell's Kitchen. J. B. Lippincott Company, 1958.

- Federal Writers Project. New York City Guide. Random House, 1939.Pages 155-160.

- Encyclopedia of New York City. Somerset Publishers, 1982

- http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/1/3/4/4/13444/13444-h/images/ill321.jpg

- http://www.vny.cuny.edu/Search/search_res_image.php?id=285

- http://www.shorpy.com/elsie_sigel