From The Peopling of New York City

The evolution and the effects of religious pluralism in Flushing.

In 1657, the citizens of Flushing penned and signed into law the Flushing Remonstrance. It promised to uphold religious freedom for all of the inhabitants of Flushing. Being the first document to establish religious tolerance in the new world, this was a monumental step in forging the multicultural America that we are familiar with today.[2]

Approximately 400 years later, the inhabitants of Flushing, sparked by differences in culture, values, and languages, are still entrenched in a struggle for tolerance. Having become one of the most diverse neighborhood in the country, Flushing would be a perfect example to explore the concepts of religious pluralism. In doing so, we will then be able to see both the positive and negative aspects of having a culturally and religiously heterogeneous community.

Contents |

History and evolution of religious pluralism in Flushing

Flushing was not always an ethnic enclave. In fact, during 1970, with 45,569 residents, Flushing had a 76% non-Hispanic white population (much of which was Irish-American). After the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, Flushing saw its own share of demographic shift. Within a span of only two decades, Flushing, a neighborhood that was predominantly White, has been transformed into a neighborhood that was 36% Asian by 1990. The non-Hispanic white population of central Flushing declined to 29%, while the total population has increased to 54,488 in 1990. Traditionally, white flight is associated with urban decay, but in Flushing the ethnic succession trend has brought an economic boom.[3]

John Bowne And His Struggle For Religious Tolerance

The story of Queens religion begins in 1657, when New Amsterdam Governor Peter Stuyvesant mandated that his Dutch Reform religion be the only one practiced in the area. A group of Quakers in the Town of Flushing known as the Society of Friends rose in opposition, which angered Stuyvesant, and led him to issue an order forbidding anyone in Flushing from admitting Quakers into their homes for any reason.[4]

John Bowne, an Englishman who was sympathetic to the plight of the Society of Friends, welcomed the Quakers into his Flushing house, where Sunday services were held in his kitchen. As disdain grew for Stuyvesant’s strict religious policies, residents saw the need for action, and in 1657, drafted the Flushing Remonstrance.[4]

The historic document stated, “We are bound by the law of God and man to do good unto all men, and evil to no man; and this is according to the Patent and Charter of our Town given unto us in the name of the States General which we are not willing to infringe and violate.” The Remonstrance extended free worship to Jews, Turks, and Egyptians, as well as Quakers. The document was signed two days after Christmas by 30 people who risked losing their jobs and their land by supporting the document.[4]

Photo by J. Davis.[4]

Bowne, who was not an original signer of the Remonstrance, continued allowing his house to be a place of Quaker worship until Dutch officials found him, jailed him, and banished him from the colony. Bowne was banished on a ship that was due to sail to “wherever it may land,” and ended up landing in Ireland.[4]

Bowne made his way to Amsterdam, and eventually pleaded his case with the colony-owning Dutch West India Company, which declared Bowne a free man. The company then sent the Dutch New World officials a note: “Let everyone remain free.” Bowne returned to his Flushing home, and the Flushing Remonstrance served as a reference for both the Declaration of Independence and First Amendment to the Bill of Rights.[4]

The "White Flight" in the 1970s

The term "white flight" refers to a demographic trend in which working and middle-class white people would move away from particular neighborhoods in the densely populated city to suburbs consisting of chiefly white people. The neighborhoods that were most effected by this phenomenon are usually racial-minority suburbs or inner-city neighborhoods. Starting from the 1990s, this trend actually began to reverse itself through another process known as gentrification.[5]

Flushing After the White Flight

Prior to the surge of contemporary immigration, Flushing was predominately a white, moderate-to-middle-income area whose residents were of Jewish, Irish, Italian, and German ancestry. In fact, during as recent as the 1960s, approximately 97 percent of the population in Flushing was non-Hispanic white.[6] All of this changed with the coming of the White Flight in the 1970s.

The exclusivity of the neighborhood remained in place until only recently. Before the 1970s, nonwhites were not welcomed into the neighborhood. For example, one long-time Chinese resident, who was married to a white American, recalled her experience about finding housing in Flushing. After arriving in 1946 to join her husband in Jamaica, Queens, they decided to move to Flushing. Quite different from the largely Asian Flushing today, she actually had to send her husband to Flushing to look for housing because, as she puts it, "...they [whites] didn't want to see Chinese here. At that time, there were few Chinese around in the community. I was not the only one, but there weren't' many...." Moreover, she also recalls that the business district in Flushing had only one Chinese restaurant and one Chinese laundry in he early 1960s.[6]

Today, Flushing is practically a completely different neighborhood. While it is often referred to as "Little Taipei," there are a number of factors that prevent Flushing from becoming a "second" Chinatown. First, Chinatown remains unmatched in terms of ethnic density. Flushing is no exception. Second and more importantly, Flushing is not dominated by any single ethnic group.[6]

Between 1970 and 1990, while the non-Hispanic white population in Flushing fell by 31 percent, the area's overall population nevertheless increased by 5 percent. This is the result of the newly incoming immigrant population replacing the former white population in Flushing.[6]

| Chinatown Manhattan CD#3 | Flushing Queens CD#7 | Sunset Park Broklyn CD#7 | New York City | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Population | 161,617 | 221,763 | 102,553 | 7,322,564 |

| Racial makeup | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 29.3 | 58.2 | 33.6 | 43.2 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 8.3 | 4.2 | 4.0 | 25.2 |

| Hispanic | 32.3 | 15.0 | 51.4 | 24.4 |

| Asian | 29.6 | 22.2 | 10.4 | 8.7 |

| Chinese | 95.8 | 41.4 | 77.6 | 48.8 |

| Place of birth | ||||

| Foreign-born | 35.5 | 39.8 | 29.2 | 28.4 |

| Arriving after 1980 | 46.2 | 49.8 | 55.5 | 45.8 |

As we can see from the above table, by the 1990s, while whites were still the majority, the presence of Hispanics and Asians were definitely more noticeable. Moreover, the white flight phenomenon is also evident by the fact that about 40 percent of the people residing in Flushing were foreign-born.

Also, by the 1990s, the area surrounding downtown Flushing had become multi-ethnic. Due to the white flight, there only remained one of the eleven census tracts in downtown Flushing with a white majority. In fact, only 24 percent of the the population in those eleven census were white while 41 percent were Asians.

Of these 41 percent of Asians in Flushing:

- 41 percent were Chinese

- 38 percent were Koreans

- 15 percent were Indians [6]

As we can see, there is barely a dominant group within the Asian population in Flushing. For the most part, these immigrant groups all believe in different religions so with their entrance into Flushing, a number of new religions will also be introduced to the community. For instance, the Chinese might bring with them Buddhism and Confucianism; the Koreans may establish their own churches for worshiping Christianity while the Indian population may establish temples for observing Hinduism. Also, we must also not forget that the white population is also divided in terms of the religions that they worship. Thus, this creates a relatively diverse mix of religions in Flushing.

Flushing Today

Flushing is now home to a large number of ethnic enclaves including those belonging to Chinese, Taiwanese, Korean, Filipino, Indian, and Hispanic immigrants.[8]

As of 2000, more then half of Flushing's population is Asian American, with the largest ethnic Chinese community in the New York metropolitan area, ahead of Manhattan's Chinatown. It is the second-largest Chinatown in United States. Flushing is also home to significant Hispanic American, African American, South Asian, Korean, and Southeast Asian populations.[9]

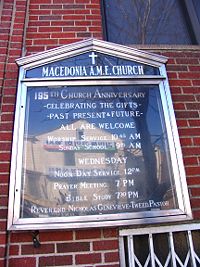

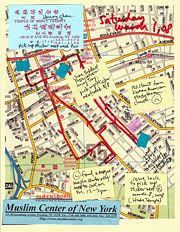

In fact, since the Immigration Act of 1965, Queens has remained one of the most diverse county in the country.[10] Moreover, it can also be argued that Flushing is one of the most religiously diverse neighborhoods in the United States. This is illustrated by the number and the variety of houses of worships found within Flushing. Walking through Flushing, one could find the colonial Dutch Quaker Meeting House, St. George's Episcopal Church, the Flushing Free Synagogue, St. Andrew Avellino Roman Catholic Church, St. Nicholas Greek Orthodox Church (the largest Greek Orthodox Church in the United States), and a plethora of modern Hindu, Buddhist, and Sikh temples.[11]

Various Religious Structures Found in Flushing Today

Impact on the neighborhood

Demographics and Statistics

| ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates: 2006 | Estimate | Margin of Error |

|---|---|---|

| RACE | ||

| One race | 2,211,839 | +/-5,430 |

| Two or more races | 43,336 | +/-5,430 |

| Total population | 2,255,175 | NA |

| One race | ||

| White | 1,019,102 | +/-12,569 |

| Black or African American | 432,815 | +/-7,605 |

| American Indian and Alaska Native | 9,243 | +/-2,061 |

| Asian | 477,390 | +/-4,540 |

| Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander | 332 | +/-240 |

| Some other race | 272,957 | +/-13,915 |

| Two or more races | ||

| White and Black or African American | 4,879 | +/-1,073 |

| White and American Indian and Alaska Native | 3,850 | +/-1,959 |

| White and Asian | 3,781 | +/-1,140 |

| Black or African American and American Indian and Alaska Native | 4,025 | +/-2,223 |

As we can see, the Asian and the African American populations in Queens are relatively balanced while the majority of the inhabitants in Queens are still White.

Moreover, we will now look at the breakdown of the Asian population in Queens as a significant number of Asians tend to congregate in the Flushing region of Queens.

| ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates: 2006 | Estimate | Margin of Error |

|---|---|---|

| Asian | ||

| Asian Indian | 147,525 | +/-10,150 |

| Chinese | 173,123 | +/-10,036 |

| Filipino | 41,784 | +/-6,105 |

| Japanese | 5,059 | +/-1,466 |

| Korean | 65,131 | +/-8,133 |

| Vietnamese | 3,688 | +/-1,751 |

| Other Asian | 41,080 | +/-5,843 |

We can see here that Asian immigrants are gradually replacing the former white population in Flushing. As such, this means that, in terms of religion, the religions practiced by those former white inhabitants will gradually decline as well. This makes sense since the people who used to practice those religions are moving out of the neighborhood.

One example of this would be how the Jewish centers and temples in Flushing, Queens are declining. The Asian immigrants are coming to push Jews that formerly lived in Flushing out of Flushing into other neighborhoods. As a result, the religious institutions that they used to worship in will therefore, experience a decline in members.

Sociological Effects on the Community

Approximately 50 years ago, the theologian John Courtney Murray asked, "How much pluralism and what kinds of pluralism can a pluralist society stand?"[13]

Back then, the United States was still largely Protestant-Catholic-Jewish.[13] However, our society is now much more diverse and with Flushing, Queens being among the most diverse places in America, it makes sense to examine Flushing as a means to explore the effects of religious pluralism.

Flushing, Queens is among one of the most extreme examples of religious pluralism. For instance, within a 2.5 miles radius comprising of a residential and commercial neighborhood, there are half a dozen Hindu temples, two Sikh gurdwaras, several mosques, Japanese, Chinese, and Korean Buddhist temples, a Taoist temple, over 100 Korean churches, Latin American evangelical churches, Falun Gong practitioners, Jehovah's Witnesses, Mormons. Moreover, some of the city's oldest churches and synagogues reside in Flushing.[13]

In short, there are approximately 200 different places of worship, all densely concentrated in a heavily populated and relatively busy urban neighborhood.[13]

The Melting Pot Metaphor

The term "melting pot" is a relatively common metaphor used to illustrate the blending of different ethnicities and culture in a particular society or community.

By the twentieth century, the melting pot concept has already been popularized and because of the continuing flow of immigration into the United States, the meaning of the concept came under debate. The debate surrounding the concept of the melting pot centered on how immigration impacted American society and on how immigrants should be approached. [14]

In essence, the boiled down to the differences between two different ways of approaching immigrants: [14]

- Was the idea to melt down the immigrants and then mold their cultural and social identities into something similar to the values and behaviors established by Anglo-Protestant models such as Henry Ford and Woodrow Wilson?

- Or was the idea that everyone would act chemically upon each other so that all would be changed and a new compound society would emerge?

Those demanding "Americanization" and "Anglo-conformity" from the immigrants regarded America as an Anglo-Saxon nation and demanded that the immigrants would culturally assimilate. Others favoring acculturation envisioned an America that would change culturally due to the impact of immigration. Not only was the way the immigrants should integrate into US society contested, there was also controversy over which and how many immigrants should be allowed in. Many Americans, the so-called Nativists, wanted to severely restrict access to the melting pot. They felt that far too many "undesirable" non-"Nordic" Americans from Southern and Eastern Europe had already arrived. As a result, The Immigration Act of 1924 was passed in order to severely restrict immigration from outside of Northern and Western Europe.[14]

Emergence of Multiculturalism

By the 1960s, research in Sociology and History has led many to discard the melting pot theory in favor of the theory of multiculturalism. By the 1990s, political correctness in the United States has emphasized that each ethnic group has the right to maintain and to preserve its cultural identity. Moreover, it is also stressed that one does not need to assimilate or to abandon one's heritage to mege into the majority European/Anglo-Saxon/American society.[15]

Many people now believe that the salad bowl theory is more accurate than the melting pot theory. The salad bowl theory stipulates that each "ingredient" of the salad retains its integrity and distinctiveness while contributing to the overall salad. In other words, not only are the identities of each component not lost but also, they are adapted in order to form a new and different identity. This differs from the melting pot analogy in that the components are not merged together into a homogeneous culture.[14]

Positive Aspects of Religious Pluralism in Flushing

- Due to the wide variety of religions permeating Flushing, there is an absence of widespread religious conflict. While there are exceptions, occurrences of bias-related crimes and hostility are relatively rare.

This leads one to wonder whether there is any limit to how much pluralism a pluralist society can withstand.

- This demonstrates how a pluralistic society committed to democracy and religious freedom can truly accommodate an enormous amount of diversity.

Negative Aspects of Religious Pluralism in Flushing

- Practical Limits to Religious Pluralism: Overcrowding may arise on days of worship when numerous observers of a particular religion all assemble to one of Flushing's many churches or temples. One such example of this would be perhaps parking problems due to the amount of cars driven by those all congregating at Flushing. [13]

- Social Limits: The residents of Flushing (and perhaps even New Yorkers in general) are somewhat more accepting of diversity. This is because not only do they encounter a wide variety of different people on a daily basis but also, they are generally forced to encounter such people due to the fact that the city is so densely populated. [13]

- Since they only come into contact with each other due to where they live, work, or worship, these interactions are not very meaningful.

In fact, you can have an apartment inhabited by people of a variety of religions and cultures, yet, many of them never really get to know one another.

- Theological Limits: Differences in religion might actually discourage people to interact with those of another religion. This might be because they believe that the other religion is wrong or evil. [13]

Personal Privacy: Limits to Diversity

People value their privacy and while they might live, work, or worship near one another, there is not much significant interaction between those belonging to different ethnic, racial, or religious groups.

As Jane Jacobs explain in her book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, privacy is an essential that everyone needs. While the degree of privacy that each person may desire can vary, we must still realize that it is absolutely necessary in a functional society. [16]

Privacy is precious in cities. It is indispensable. Perhaps it is precious and indispensable everywhere, but most places you cannot get it. In small settlements everyone knows your affairs. In the city everyone does not—only those you choose to tell will know much about you. This is one of the attributes of cities that is precious to most city people, whether their incomes are high or their incomes are low, whether they are white or [black], whether they are old inhabitants or new, and it is a gift of great city life deeply cherished and jealously guarded. [16]

As such, it can be argued that religious pluralism is only beneficial when it is not excessive. When it does become excessive, there is a chance that it might be invading and depriving people of their essential personal privacy. When there are simply too many religious institutions cluttered into a limited space, instead of satisfying each of those religious enclaves, it might cause conflict and tension between them. This is because one group might feel as if their collective personal privacy is being encroached upon by another group.

Personal Interviews

- Alcalay, Alfred. Personal interview. 04 May 2008.

Local Resident (born in the United States)

- Temple goer

- He talked about the Kissena Jewish Center not having sufficient attendance. Moreover, the Free Synagogue of Flushing, a Reform temple on nearby Kissena Boulevard, is facing the same situation. As a result, they find themselves having to rent out their worship halls to a Korean Presbyterian congregation on certain Sundays.

- This shows that certain religious and ethnic groups are indeed being pushed out by those with a larger worshipers base.

- Huyhn, R. Personal interview. 26 April 2008.

Local resident (Foreign Born)

- Chinese Christian

- He does not interact with people from other houses of worship.

- He occasionally waves and says "hello" to his neighbors but the interaction is pretty much limited to that level.

- Khan, A. Personal interview. 26 April 2008.

Local resident (born in the United States)

- Main complaint was the parking and the congestion brought upon by the commuters.

- Mukherjee, Aditya. Personal interview. 04 May 2008.

Commuter (Foreign Born)

- He did not mind the numerous churches.

References

- ↑ L'Arte D'Arrangiarsi. Accessed 4 May 2008.

- ↑ Flushing Remonstrance Accessed 10 May 2008.

- ↑ Smith, Christopher J. (Spring 1995). Asian New York: The Geography and Politics of Diversity. International Migration Review 29 (1): 59-84. doi:10.2307/2546997. ISSN 01979183.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Kivell, Jonathan. The Birthplace of Religious Freedom: Continuing To Welcome The World's Faiths. Queens World 2002. Accessed 11 May 2008.

- ↑ Kruse, Kevin M. White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism. Princeton University Press. 2005. ISBN 9780691133867.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Zhou, Min. Chinese: Divergent Destinies in Immigrant New York. New Immigrants in New York. Ed: Foner, Nancy. New York: Columbia University Press, 2001.

- ↑ New York City Department of City Planning 1992b, 1993

- ↑ Queens Community Boards, New York City. Accessed April 28, 2008.

- ↑ Lange, Alexandra. (2006-06-05). Flushing in 2016. New York. Retrieved on 2007-07-05.

- ↑ Quick Demographic Profiles: Queens. The Ecologies of Learning Project - a Project of NEW YORK THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY. NYTS - Ecologies of Learning Project. 4 May 2008

- ↑ A Religious History of Flushing, Queens, From the Flushing Remonstrance until Today, Ronald J. Brown, Sacred City Books, 2007, ISBN 978-0-9795092-0-9

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Queens County, New York - ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates: 2006 U.S. Census Bureau. Accessed May 4, 2008.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 Hanson, R. Scott. Public/Private Urban Space and the Social Limits of Religious Pluralism. Philadelphia University.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Melting Pot. Wikipedia. Accessed May 10, 2008.

- ↑ Milton Gordon, Assimilation in American Life. New York: Oxford University Press, 1964.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Jacobs, Jane. The Death and Life of Great American Cities.