From The Peopling of New York City

History of Chinatown: Buildings and Boundaries

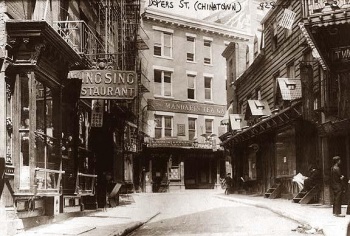

Chinatown, N.Y.C. Doyers St. 1909.

Old Chinatown was first established in the late 1870s near the Five Points slums, centered around what is today Mosco, Worth, and Baxter Streets. By 1880, between 200-1,100 Chinese had settled in this area, their little enclave steadily growing. The Chinese Exclusion Act, passed in 1882, made it impossible for Chinese immigrants to legally enter the country; nevertheless, many Chinese continued to arrive and settle in the United States using a variety of means, the continued racism and disdain of the rest of society further supporting the growth of Chinatown as its own isolated community [1,2]. The repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943 allowed the immigrants from China to once again hold legal status yet imposed a strict quota of 105 new arrivals annually [3]. It was not until the Immigration Act of 1965 that the Chinese, along with other Asians, experienced a much greater rise in the percentage of total annual immigration. Chinatown, in turn, experienced much expansion in light of all these new people who sought to live and work there, looking for community and sense of familiarity. By 1970, Chinatown had encompassed an approximate quarter-mile square south of Canal Street, pushing at the Bowery on the east, Worth St. on the south, and Baxter St. on the west [4]. Within the next decade, this swelling enclave would spread north of Canal and absorb much of Little Italy, which today has been reduced to a few blocks centered on Mulberry Street between Canal and Broome Streets [5].

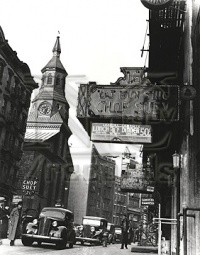

Chinatown, 1936. Looking north on Mott St. from near Park St. (now Mosco St.)

Chinatown, today. Looking north from the corner of Mott and Mosco

Today, Chinatown continues to grow; its approximate borders are Grand St. to the north, East Broadway to the east, Chambers St. to the south, and Broadway to the west [6]. It dips into the Lower East Side, pushes against SoHo and TriBeCa, and encroaches on City Hall. The immigrant face has changed as well: from the Eastern European Jews, Chinese, and Italians of the first immigrant wave of the late 1800s to early 1900s; to the majority of Chinatown residents today from the Guangdong, Toisan and Fujian Providences in China as well as Hong Kong, with their well established Cantonese community, of the second great immigrant wave; to the recent Fujianese immigrants of the last decade or two, who come from the Fujian Province on the southern coast of mainland China [7]. However, just as Chinatown pressed at and shrank the boundaries of Little Italy, the other more affluent neighborhoods of downtown Manhattan appear to be placing stress on this old ethnic enclave today. Chinatown has long resisted gentrification, but many of the new construction projects going on currently seem to be geared more towards middle- and upper-income households (who would traditionally find themselves living comfortably in areas such as SoHo and TriBeCa), rather than for the old residents of Chinatown, mostly low-income and working class [8].

For the newest immigrants, such as many of the newest Chinese in Chinatown, living arrangements were, and largely continue to be, tenement housing.

Tenement buildings of the LES in the early 1900s

Tenements generally refer a dwelling that houses multiple families. Historically prevalent in low-income neighborhoods, beginning particularly in the Lower East Side for the influx of immigrants in the mid- to late-1800s, tenements were built as housing that “sought to maximize their owners' profits by squeezing the largest number of people onto a given site, which was usually the standard row-house lot” [9]. People lived in squalid conditions, large families cramped into tiny spaces with poor ventilation, lighting, and sanitation. Here is a description of a typical tenement of that time (97 Orchard St., which has today been preserved and converted into the Lower East Side Tenement Museum):

Five stories with basement. Designed to house 20 families: 20 three-room apartments, four per floor, two in the front and two in the back. Running through the center of the building is an unlit wooden staircase and narrow hallway. The largest room (11' x 12'6") is listed on plans as the living room or parlor, commonly called "front room” – the only room with direct light and ventilation. Behind it is the kitchen and bedroom (8’6” square). The entire flat, which often contained households of seven or more people, totaled about 325 square feet. No toilet, shower, or bath. Heat available by fireplace and/or stove in kitchen. All garbage is left outside the building.

[10]

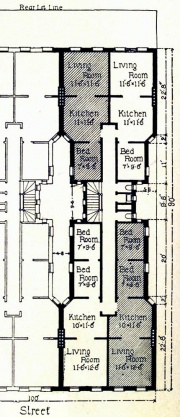

Standard tenement floor plan. Note the "dumbbell" shape

In 1879, the passing of the Tenement House Act created new mandates for basic amenities in attempt to improve these horrible conditions where sickness ran rampant. One thing these “oldlaw” tenements would include were shallow side shafts on the side of the building, designed to provide air to interior rooms. These air shafts caused the floor plans to be shaped like dumbbells (resulting in the name “dumbbell” tenements). Another Tenement House Act passed in 1901 ("newlaw" tenements) mandated illumination from sunset to 10 P.M., which called for the installation of a light near the entrance, and a ventilating skylight over the stair.

Today, although there is electricity and plumbing, conditions in these tenements continue to leave much to be desired. Tenements, “now defined as a pre-1929 building that houses three or more unrelated people who cook in their apartments and share a common hallway, constitute a full 30 percent of New York's housing stock, accounting for 833,437 of the 2,868,415 units citywide. At the beginning of the 21st century, an estimated 3 million New Yorkers call tenements home.” In the past few years, spanning the 1990s into the new century, tenants have filed a multitude of complaints (averaging 250,000). These range from “rat infestations to lousy plumbing and lack of heat” [11].