From The Peopling of New York City

One of the most important practices in Judaism is keeping the Sabbath as a day of rest. Jews do not work on Saturday, and at a time when the standard work week was Monday through Saturday it was very difficult for immigrants to get jobs. The ultimatum "If you don't come in Saturday, don't come in Monday" was common for many employers during that era, and Jewish immigrants were forced to make a choice: keep Sabbath, or survive.

There were some who did not waver in their dedication to Sabbath, and had to search for a new job every week. Most immigrants, however, gave in to their instincts for survival, and in 1913, more than half the retail shops and pushcarts on the Lower East Side were open to customers on Saturday, as well as most of the garment factories. The need to survive, along with secular political movements drew away many of those Jews who were religious in Europe just out of habit, and Friday night and Saturday became favorite times to attend Yiddish theater.

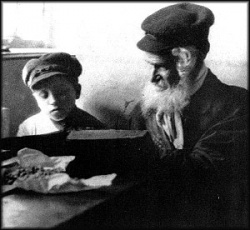

Education of children is another extremely important part of Judaism. Since children are the future of the nation, it was important to educate them properly so that they could one day raise a Jewish family of their own. At the turn of the twentieth century, however, facilities for religious education were severely lacking. Trained rabbis were difficult to find, as many of them stayed in Europe to help the remnants of their congregations. Often parents did not insist on providing their children with a religious education, arguing that learning a job would help them survive, learning Scriptures would not. In 1914, less than a quarter of the 275,000 Jewish children between ages six and fourteen were learning about their religion beyond what they observed at home. This religious downturn was eventually slowed by the Young Israel movement, founded in 1912. Young Israel synagogues offered a balance between the traditional Yiddish sermons on strictly religious topics and the totally secular Reform movement. Young Israel rabbis were educated in secular areas as well as religious ones, and could give sermons and lectures in English on a wide range of topics. [1]

Kosher food was another problem for immigrants to the U.S. The Torah (Hebrew scriptures) prescribes specific dietary laws, regulating what food may be eaten, and how it must be prepared. The need to control the production of kosher food led to the organization of agencies such as the Orthodox Union, or OU (founded 1898). Often parents allowed children to eat what they wanted outside, but insisted they keep kosher at home.[2]