Politicsandorganizations-url

From The Peopling of New York City

Contents |

Politics in East Harlem

Current Politics

Key Players

City Council Woman Melissa Mark-Viverito

In November 2005, Melissa Mark-Viverito became the first Puerto-Rican woman elected to the District 8 City Council, which serves East Harlem (“Viverito Bio”). Mark-Viverito’s policies, in keeping with East Harlem’s Democratic reputation, reflect liberal values. One of her most progressive causes is that of the vote for legal U.S. residents in local elections (Viverito). Indeed, voting is one of the most prominent issues on Viverito’s webpage. The focus is not only on expanding the vote in local elections to legal residents, but on extending voting hours and allowing for voter registration the day of the election. Mark-Viverito also supports a decentralization of power of the Speaker, allowing individual members of the City Council to possess greater sway. Other issues Mark-Viverito is concerned with are increasing affordable housing in East Harlem, proliferating small businesses, and creating job training and employment opportunities; she is particularly focused on achieving such goals for minority groups and women. In addition, she is also concerned with health standards and the distribution of insurance to poor families (Viverito).

Congressman Charles Rangel

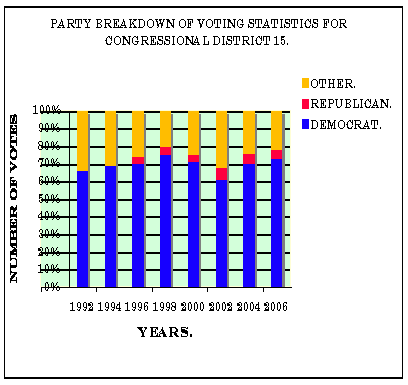

Elected in the 1970s, Charles Rangel has been the representative from the 15th Congressional District (East Harlem, Central Harlem and the Upper West Side) for three decades. Rangel is a founding member and former chairman of the Congressional Black Caucus. As a Black Congressman, he has been criticized by several in the Latino community for focusing on Central Harlem and the African American community. As a representative, he has fought against drug abuse and drug trafficking and authored the Federal Empowerment Zone project and the Low Income Tax Credit; both are meant to help low income neighborhoods. He is also a ranking member of the House Ways and Means Committee.

Assemblyman Adam Clayton Powell IV

Adam Clayton Powell IV, the son of famed civil rights leader, Adam Clayton Powell Jr., is the representative for the 68th New York State Assembly District, which includes both Harlem and East Harlem. Powell, who is a mix of Puerto Rican and African-American descent, has received considerable criticism for ignoring the needs of East Harlem. In fact, during the 2004 election for the seat Powell currently holds in the New York State Assembly, Councilwoman Melissa Mark-Viverito, one of Powell's critics, supported his opponent. Further, according to an article in the New York Sun, as of March 2007, Powell had not introduced a new bill for three years. Powell has also had his share of scandals during his time in office. In 2004, a woman accused Powell of raping her, although no criminal charges were filed against him. Earlier this year, Powell made the news yet again, this time, because he was charged with driving under the influence. Still, Powell asserts that he is an active voice in the East Harlem community who championed programs like the Senior Citizens Rent Increase Exemption (SCRIE) legislation, which helps ensure that senior citizens apartments' are rent-stabilized.

Senator Jose M. Serrano

State Senator Jose M Serrano took office in 2004, after defeating the 26-year incumbent, Olga Mendez, for the seat in the (Hicks). He serves the 28th Senate District, which includes parts of the Bronx in addition to East Harlem. Senator Serrano has chaired several committees, including Chair of the Council's Committee on Cultural Affairs, Libraries, and International Inter-group Relations and The Senate Minority Task Force on the Arts and Cultural Affairs. Some of his major causes involve immigrant rights, community improvements and the creation of green space in East Harlem, English as a Second Language (ESL) and youth literacy programs, funding for the arts, etc (“Jose M. Serrano”).

Former Senator Olga Mendez

Olga Mendez’s downfall reflects one very key facet of East Harlem: It is a wholly Democratic neighborhood. Although Mendez is not a current politician, she is important to mention in order to provide a context for both the current and past politics of the neighborhood. Mendez, who served as a senator in East Harlem for 26 years (Hicks), after winning a special election in 1978 and becoming the first Puerto Rican public official (Democrats for Pataki), was initially a registered Democrat. But after switching her party affiliation before the 2004 election, Mendez’s political career was doomed to its end. The district, “where there are 10 registered Democrats for every Republican” (Hicks), failed to back Mendez in the 2004 election, voting for her Democratic competitor, Jose M. Serrano, instead (Hicks).

Social Justice

Social Action Groups

East Harlem, better known as El Barrio by Latino New York, has been a neighborhood recognized for community-based movements fighting unjust living conditions. It is recently plagued by the problems incited by wealthy gentrifiers and multinational corporations making it more difficult for an already struggling, low-income community to sustain itself. In this section, I will focus on two community-based organizations located in East Harlem: Esperanza del El Barrio (Hope of Del Barrio) and Movement for Justice in El Barrio (Movimiento por justicia en El Barrio). Though the issues amongst the newly arriving immigrants and long-situated Puerto Ricans and African Americans should not be overlooked, I will discuss the efforts of Mexican immigrants to use Zapatista-influenced methods to bring together diverse, marginalized groups to fight against gentrification, as well as Esperanza’s work on ending anti-immigrant practices.

Movement For Justice in El Barrio

Movement for Justice in El Barrio (MJB) was borne out of Saint Cecilia’s Church on 106th Street in 2004 when residents began to organize against problems with their landlords. Led by Juan Haro, a Mexican immigrant and founding member of AZUL (Amanecer Zapatista Unidos en la Lucha), MJB became an immigrant-led, community-based organization that would study other locally based social justice movements and apply what they learned to their own work. By organizing open forums for community members that would facilitate dialogue and decision making, MJB, following the steps of previous social action groups, went door knocking and called East Harlem residents to find out the major problems in El Barrio. After 782 immigrants cast votes, MJB decided to organize around gentrification, low paying jobs (below minimum wage), bad services at the Mexican Consulate and the proposed immigration laws.

As a Zapatista-inspired movement, MJB sees the connection between local problems and global issues. To fight the problems in their community, they see the need to organize against multinational corporations. Currently, they are waging a fight against the Dawnay Day Group based in the U.K. After organizing against Steve Kessner, considered one of the worst landlords in New York, Dawnay, Day Group bought forty seven rent-stabilized and rent-controlled buildings in East Harlem for $250 million (http://www.nydailynews.com/ny_local/2007/08/12/2007). Attracted by the lax tenant protection laws in New York City that would enable them to displace current tenants, Dawnay Day has created a dangerous, unsuitable environment for many of his working-class residents by refusing to repair damages and charging them for the cost of repairs and sending threatening letters, accusing tenants of crowding. To counter such instances, MJB uses non-violent tactics such as protests, media tours, court action and direct action to fight back. To combat this problem in particular, MJB has begun an International Campaign in Defense of El Barrio, which is sending members to the UK and Spain (as well as Texas and California) to broaden their base. They have also taken part in the NYC Encuentro for Dignity and Against Gentrification where various organizations came together to discuss the wide range of gentrification and how to fight it.

Esperanza del Barrio (Hope of El Barrio)

Esperanza del Barrio is a small center located on 2nd Ave and 117th Street, boasting over 500 members from East Harlem, Queens, Brooklyn and the Bronx. Created by five Latina women in 2003 that were fed up with police abuse and anti-immigrant practices from city authorities, the organization specifically began its efforts to help street vendors organize to remove licensing caps and fight police harassment. Street vendors must get their license from the Department of Consumer Affairs; however, there is currently a legislative cap of 853 licenses and thus a waiting list of thousands. In addition, food vending requires a license from the Department of Health, and a permit for a food cart, which has a cap of 3000, which have already been issued). As a result, there is a disparity: while there are 9000 food vendors with licenses, only 3000 of those have food cart permits, making it impossible for 6000 vendors to work legally. In an effort to unite vendors and remove limits to the number of street vendor licenses and permits issued, Esperanza has a biweekly community meeting every other Monday of the month and works with the Street Vendors for Justice Coalition.

Aside from this major issue however, Esperanza has several programs that work to empower their community such as leadership development workshops that focus on teaching direct representation and self-advocacy, adult education programs that teach English as a Second Language and practical and applicable classes on running a business and sanitary food preparations. Because much of their membership is made up of young to middle aged immigrant women, they have health programs that focus on topics for uninsured women. Another of their programs is focused on organizing and empowering youth around issues such as the Dream Act and anti-violence campaigns. Most importantly, they have a legal assistance program that does referrals and helps document and report abusive treatment by police officers, as well as legal education workshops.

Banking

Red-Lining: a discriminatory practice by which banks, insurance companies, etc., refuse or limit loans, mortgages, insurance, etc., within specific geographic areas, esp. inner-city neighborhoods.

This was the plight of East Harlem for many years, especially in the late 1980s till early 1990s, and a major issue emerging in the politics of the neighborhood. The banks and capital investors were choking the financial opportunities of the neighborhood. Chase and Chemical Banks both closed all of their branches in 1987 (1), leaving Banco de Ponce and Banco Popular as the major banks serving the needs of the community. In 1990, these two banks announced that they were going to merge. The East Harlem Community Coalition for Fair Banking took this opportunity to attack the banks, claiming that they had to meet the needs of the people in the community. At this time, there were no automatic teller machines (ATM) north of 97th street and east of 5th avenue (1). This was completely unacceptable, when, there were only seven bank branches (2) serving the needs of the entire community (108,513 people according to the 1988 census).

The Bank Report for 2000-2005 shows that there is a correlation between the median household income of the neighborhood, and the number of banks present. According to the 2005 census, the median household income of East Harlem was $18,564, compared with $38,293 in New York City. Between 2000 and 2005, there was an explosion of new bank branches in New York City, an increase of 213 branches, yet, there was no change in East Harlem. This is a common pattern for New York’s 20 poorest neighborhoods, where only four neighborhoods increased their number of banks at all, whereas nine of New York’s richest neighborhoods increased their number of banks by at least two.

Another problem the East Harlem Community Coalition decided to tackle was the Banks failure to comply with Federal Community Reinvestment Act (1977), “provided that banks should commit some of their resources to the neighborhoods where they take deposits” (1). The laws were vague, but the community group gained an advantage when their push for amendments “providing that bank reinvestment statistics” (1) be made public later in 1990. These public files will help keep the banks in check. In the late 1980’s, Banco de Ponce reinvested between zero and half a percent of the amount that the community had deposited into the bank that year (1). Banco Popular held over $200 million in deposits from the community in the years 1987 and 1988, yet it only loaned out $2.6 million in 1987 and $2 million in 1988, and even this money mostly was not loaned out in New York. Community members complained that the Puerto Rican based banks made Puerto Rico their first priority when lending out money instead of the community supporting them (2).

This was a very important gain for the community of East Harlem. Before the banks were made to show their reinvestments, and before there were ATMs, financing was very difficult for the people of East Harlem. According to the Bank Report for 2005: Access to financial institutions is crucial to the mobility of a person struggling from the lower-class to the middle class and beyond. New Yorkers without a personal bank account are forced to use alternative financial services like check cashing stores. Pay day loans, which are used by check cashing stores, are often equivalent to an Annual Percentage Rate (APR) ranging from 391% to 443%. A person making $12,000 a year will spend roughly $250 a year just to cash their payroll checks. (3)

This is a huge problem that many people in more affluent neighborhoods would never even think of. It is also an effective way of keeping people from low-income homes from advancing financially. When banks ignore these neighborhoods, they also ignore the people who live there. Things such as cashing a paycheck should be fairly easy. The community of East Harlem realized that they were being treated unfairly, and so they united to fight this for this cause. They knew that by virtue of living in America, there should be regulations that would make life easier. They knew that small business owners should not have to borrow from their credit cards to finance their businesses when the Banks tell them that there are not any more small business loans to be given out. Because of the actions of the East Harlem Community Coalition, the banks will not be able to easily get away with reinvesting the small amount of money into the community that they had been used to giving back. From 1990 to 1995, Banco de Ponce agreed to put $5 million back into East Harlem in the form of housing loans, and $10 million into the rest of New York City, also in the form of housing loans (1), this time defining New York City precisely as the five boroughs.

Where Does the Tension Lie?

Racial tensions between Puerto Ricans, other Hispanic groups, and African Americans are only part of the equation, when it comes to politics in East Harlem. Although it is known as Spanish Harlem, the neighborhood is a melting pot where different ethnic groups co-exist, sometimes peacefully, sometimes less so. But, beyond ethnic divisions, there are other, more subtle forces at work as well.

On a trip to a March 18th meeting of Community Board 11, the board which represents East Harlem, there was a great deal of hostility. Board members argued for several hours over the minutes. At other community board meetings I have been too, approving the minutes is fairly routine and quick. Here, however, some people seemed overeager to voice their opinions; they all wanted to have a say, even on seemingly insignificant issues like the minutes for each respective committee meeting. Again, at most community boards, committee meeting minutes are approved, if at all, by the committees themselves. Here, however, the general community board went through the minutes of every single committee meeting individually. The board’s need for such a procedure suggests that there are some underlying tensions amongst members.

Tension not only existed within the community board, but also between community board members and outside entities. For instance, many board members expressed fury at developers from the Hope Community Inc. & The Bluestone Organization, who came to the community board seeking approval for an affordable housing development proposal in the community. While many board members were pleased with the overall proposal, they were outraged at the developers for not coming prepared with sufficient materials highlighting specific details of the project, such as the average rent of the housing units in the development. Several board members lashed out at the developers upon discovering that the developers failed to provide what they deemed key information. They argued that the developers lacked respect for the community, and demanded that the developers leave the meeting, obtain the information and make copies for the community board, and finally, return so that the community board would have adequate information to vote on whether or not to give the development the green light. The community board approval of the project is part of the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP), which was required because of a change in land use being requested by the developer. While the board did finally end up approving the project, it did not do so without controversy. Even after the project garnered the board’s approval, community board members were still on edge about the approach to voting on the project.

For some members, the confrontational atmosphere during the discussion and voting on the project reflected an overarching problem in the community board. One board member felt that some people argued for the sake of arguing, and that people automatically and often incorrectly assume that developers and other outside organizations have selfish motives in East Harlem. She asserted that small developers, such as the Hope Community Inc. & The Bluestone Organization, are often unfairly scrutinized by the board, as compared to larger organizations. Another board member added that small organizations in general are treated unfairly by the board. This led to larger discussions on a lack of respect within the board as whole.

Councilwoman Melissa Mark-Viverito also took part in the discussion, confronting the board about the tendency of many members to abstain from voting. Mark-Viverito vehemently argued that abstentions are simply a cowardly mode of voting “no” on an issue. She was very confrontational towards the board, and they, in turn, criticized her for passing judgment on the board when she only attends meetings once every few months.

On the surface at least, the tension did not seem to originate from issues of race. But, further research indicated that race might, in fact, be a part of the equation. Commentary found in EastHarlem.com political forums helped to explain the racial politics of the neighborhood. As of 2001, African Americans made up 50% of the community board in an area only 38% African American, but 47% Hispanic (Rivera). Many people feel that there is a “Harlemization of Spanish Harlem,” that is, representation in Spanish Harlem mirrors the demographics of representation in Harlem (EastHarlem.com). But East Harlem, as compared to Harlem, which is overwhelmingly African American, has its own distinct set of needs.

According to EastHarlem.com, the political machines in Harlem have taken advantage of the fact that Hispanics in East Harlem “have not voted in proportion to their numbers.” An article on the website claims that “the Manhattan African-American leadership has chosen to colonize Spanish Harlem as oppose to assisting local Hispanic leadership bloom” (Rivera). The piece asserts that the overpowering African American representation in East Harlem exists in order to expand Harlem “to the advantage of Harlem Political/Business interests.” The article concludes that “a strong Hispanic community board # 11” is essential in counteracting this perceived “Harlemization” of East Harlem. It opposes the putative argument that there are “not enough ‘qualified’ Hispanics,” asserting that that line of reasoning is just an “excuse” (Rivera).

One anonymous member of the EastHarlem.com forums started a discussion on exactly this problem, noting that, “CB 11 is a little fawning of CB 10,” the community board which represents Harlem. He added that, “the Latino board members are more connected to the community [than the African American board members], but not in a position to affect (sic) too much on their own.” Yet another discussion thread posted on the website, entitled “Current Board Composition Stinks!” speaks to the same issue. The administrator of EastHarlem.com replied to the thread saying, “I can't say too much publicly (but a lot privately),” indicating that racial politics in East Harlem do cause tension, but much of the tension goes unspoken about (EastHarlem.com)

Politics of the Past

Housing

Politics in East Harlem throughout the 1980's, 1990's and present decade have been marked by a feeling on behalf of the community's residents and political leaders, that the interests of the City government and it's affiliated organizations are in conflict with those of the East Harlem community. Such sentiments find clear bases in the City's proposals for the development of land in East Harlem. Repeatedly, departments such as the City Planning Commission, Economic Development Corporation and the Mayoral office itself, have drafted suggestions for land development that if adhered to, would aggravate many of the ongoing problems that East Harlem faces. During the 1980’s, The City Planning Commission proposed numerous land development suggestions, which would have tailored the effected regions of East Harlem to the interests of more affluent buyers. Many of the politicians of East Harlem saw such suggestions as efforts that could render housing in the neighborhood unaffordable to many of its long time residents. One such proposal, supported by Mayor Koch in the 1980’s intended to auction off 20 brownstones in East Harlem, that were owned by the city. East Harlem’s Community Board 11 opposed this plan, addressing the fears of the neighborhoods residents that “tenants into he area are being evicted to make way for monied people”. In response to these worries of displacement, Board 11 sought to form a plan to dispose of over 300 buildings, which were previously owned by the city. Eugene Rodriguez, who was the chairman of Board 11 at the time, explained that the drafted plan would lottery off most of the buildings to residents of the East Harlem community. The Community Board also refused suggestion of the Department of Housing Preservation and Development to work alongside Community Boards 9 and 10. The plan proposed by Board 11, and their unwillingness to collaborate with other community boards, displays the value placed on independence in East Harlem’s politics. The community board sought to benefit the residents of the neighborhood against the threat of city-sponsored gentrification, and it sought to do so alone, to avoid the possibility of the self-interest of outside groups.

Public Health

Proposals of the City government threaten to further not only East Harlem's problem of affordable housing, but problems of public health as well. In 2006, Community Board 11 again, drafted a plan of their own to counter a plan proposed by the city. The Economic Development Corporation had intended to devote 700,000 square feet of city owned lots between 2nd and 3rd avenues and spanning from 125th to 127th streets to commercial development. The space would also include 1,000 parking spaces, MTA bus storage facilities and 1,500 housing units. In response to this proposal, East Harlem’s Community Board organized a task force and held a meeting at town hall to enumerate the qualms that they had with the city’s plan. The results of such work were the reopening of discourse on the fate of the contested land. Lino Rios, the chairperson of Board 11 at the time, described the intended fate of the plot to be to ”create housing which is truly affordable while providing real economic development and employment opportunities for the residents of East Harlem. “ The desire of East Harlem’s politicians were adhered to, as their work enabled them to have the opportunity to define the use of their neighborhood’s land by their needs rather than by the desires of the city. At the heart of this battle was not only East Harlem residents’ need for more affordable housing, but also the need for better health conditions in the neighborhood. The proposal of the city’s economic Development Corporation to include facilities for bus storage and car parking had the frightening potential to severely exacerbate the issue of Asthma, one of the community’s most prevalent health concerns. The politicians of East Harlem took local health into account when opposing the development plan, addressing a common fear that the tentative influx of motor vehicles would further the trouble of Asthma in the community.

Go Green and the Creation of Farmer's Markets

In response to East Harlem's poor health conditions, politicians have also worked to provide the neighborhood's residents with means to eat and cook in wellness promoting ways. East Harlem's residents, feeling as though their neighborhood has been "enviromentally neglected", were provided with a number of new farmer's markets under an initiative entitled Go Green East Harlem. Community Board 11, along with a number of not-for profit organizations, hospitals, and State Senator Jose Serrano have endeavored since 2007 to make fresh produce and information on nutrition to East Harlem. In conjunction with Go Green, a bilingual cookbook was printed, featuring healthy recipes written by community members including Board 11 Chairman Robert Rodriguez.

Accessibility of Services

As well as environmental health conditions, politicians have focused their health considerations on the quality of services available to East Harlem’s residents. Quality and accessibility of services, however, sometimes had to be weighted against the worry of displacement. Much like residents seeking to preserve affordable housing, many small business owners in East Harlem harbored the fear that the opening of corporate business in the neighborhood would drive small vendors out of business. In 1993, a 53,000 square foot Pathmark was proposed to be built on 3rd avenue and 125th street. Mayor Rudolph Giuliani supported the project, while many leading East Harlem politicians, such as Adam Clayton Powell IV and City Councilmen and Charles Millard and Antonio Pagan, as well as East Harlem’s Hispanic merchants, opposed it. The question of the Pathmark store was multifaceted, however, as the building of such a superstore promised to make a wide range of necessary products more accessible to East Harlem’s residents. Furthermore, although many Hispanic merchants feared the competition with which the store threatened their businesses, many residents of East Harlem, most notably the neighborhood’s black residents, saw the opening of a Pathmark store as an opening for many new chances for employment. Community Board 11 eventually gave their support to the development of the Pathmark, realizing that it would indeed, bring more jobs into the community. The battle over the building of a Pathmark on 125th street exemplified not only the neighborhood’s conflict between the need for sufficient services and the fear of displacement of small businesses, but also the existence of racial politics. News coverage described the support and opposition of the Pathmark to be drawn along racial lines. This displayed the disparity of interests among the neighborhood’s various ethnic enclaves, despite the solidarity of residents and politicians against attempts at gentrification.

Poor services have affected people not only in the sectors of commerce and health, but also in the ability of many East Harlem residents to express a political voice. Sub par voting services have repeatedly made it difficult for East Harlem residents to cast their votes. Polling stations are sparse and in some cases, polling station attendants have been late to show up. Furthermore, although many of the residents of East Harlem during the 1980’s and 1990’s were not native English speakers, bilingual services at the polls were not provided. Some residents of East Harlem were unable to vote at all, due to the difficulty to reach a polling station and still be able to attend work. The lack of provisions for voting, in effect, bar many of the residents of the community from expressing their democratic will. Poor voting services in Harlem provide an example of the bases of the sentiment shared by many of the neighborhood’s residents, that their city government has abandoned the neighborhood.

"A Lack of Concern"

As the 1990's drew on, the City government came to realize the power of race in East Harlem's political life. In 1992, as support for Mayor David Dinkins was faltering in East Harlem, the mayor sought to publicize his support of the Hispanic community. Alan Finder, writing for The New York Times, described the Mayor as heavily concerned with appearing as a champion of the Hispanic community, stating that "he seldom misses an opportunity to boast of the many Hispanic New Yorkers he has appointed to senior positions. When he mentions the most senior, Cesar Augusto Perales, who was named a deputy mayor last November, Mr. Dinkins almost always recites Mr. Perales's complete name and even attempts the proper Spanish intonation." However, many residents and politicians of East Harlem felt that Dinkins' actions, in reality, did little for the people for whom he supposedly worked. Adam Clayton Powell IV stated on the issue "As I walk the streets, the Mayor is not doing very well...the administration just doesn't seem concerned about the feelings of the community." Although the Mayor recognized the importance of appearing to care for East Harlem's racial niches, the neighborhood's residents continued to lack trust for their City government, due to the continued assumed failure of the government to improve the problems of the community.

East Harlem has been a traditionally Democratic neighborhood.

Olga Mendez

Social Organizations of the Past

The Young Lords

“If our people fight one tribe at a time, all will be killed. They can cut off our fingers one by one, but if we join together we’ll make a powerful fist” (Gonzalez).

- Little Turtle, Master General of the Miami Indians, 1971

Just like the plight of the Native Americans during the white Europeans imperialistic take over of their land, immigrants in America have faced extreme amounts of antagonism on arriving in America, and like the Native Americans, their response has been to join together in protest of how they are being treated. In East Harlem, an area in New York City that has been home to many generations of immigrants, and continues to be a haven for newly arrived foreigners, the importance of “a powerful fist” has been particularly seen. One of the most widely known political organizations that developed in East Harlem as a result of extortion and discrimination was the Young Lords, an organization that was extremely influential and popular in the 1960’s.

The New York City Young Lords party was founded by “Cha Cha” Jimenez. Jimenez was a Puerto Rican activist who, while in prison, met several Black Panther members who were responsible for igniting in him a fire to protect the oppressed and taken advantage of. In 1968, he founded the Young Lords Organization by collaborating with the formerly known Young Patriots Organization, a local street gang. First, the organization set about creating a thirteen-point program that was modeled after the Black Panthers’ ten-point plan. The Young Lords Organization (YLO) program involved addressing the “issues concerning prisoners, women, the working poor, Vietnam War veterans and high school students” (“Latino”). Interestingly, the organization encouraged immigrants of a variety of races to become members, including people of European, Native American, and African descent. They wanted their organization to represent “the variegated cultural and racial demography of Puerto Rico and the barrios without the prejudice…” (Nelson). In July 1969, the YLO demonstrated its growing influence in a protest against the sanitation department. According to the YLO, the department had not equally serviced the poor black and Latino neighborhoods. To protest, they created a community sanitation project. The members piled garbage in the middle of the street, preventing cars from passing through and forcing the sanitation department to collect it (“Our Herstory”). The next protest they conducted was in December 1969 against the Lexington Avenue Methodist Church. The church had refused their request to use its basement to provide “free community services” such as “a breakfast program, health clinic, and day-care center” (Nelson). They were able to take over the church and for eleven days following their take-over of the church they provided desperately needed free services (Nelson).

In April and July of 1970, the YLO took over the Lincoln Hospital in the South Bronx, a building that had been scheduled for demolition even though it was the only medical facility servicing local residents. During the occupation, YLO used the hospital to establish a drug rehabilitation program that ended up treating 500 patients weekly. YLO’s actions resulted in an agreement to build a new Lincoln Hospital for the neighborhood (“Latino”).

The Young Lords Organization was also a dedicated advocate for Puerto Rico’s independence. In 1971, the YLO teamed up with the Puerto Rican Student Union (PRSU) and brought together 1,000 students for a conference at Columbia University to establish “Free Puerto Rico Now Committees” in high schools and colleges. It also initiated a march of 10,000 people to the United Nations from El Barrio to “demand the independence of Puerto Rico, freedom for political prisoners and an end to police brutality” (“Latino”).

The Young Lords Organization is just one immigrant group in many that were created during the 20th century. A more recent example of oppressed groups of people using their strength as a group to make a difference in their community was the creation of the Community Association of the East Harlem Triangle. The association was created in 1961 by Alice Kornegay, and was used to protect the best interests of the East Harlem community. Kornegay secured financing for the construction of low-income housing and helped establish important institutions in the neighborhood, including the Beatrice Lewis Senior Center, the East Harlem Senior Center, and the Salvation Army Center. Though the Young Lords Organization was almost completely destroyed by government actions, including police intimidation and negative propaganda (“Latino”), Kornegay’s organization is still alive today and continues to protect the interests of the people (“Alice Kornegay”).

Another social organization that has survived through many years of political and societal changes is the Union Settlement Association, which was created in 1895. This association is used to create programs to better the community, such as with programs in education, childcare, job training, and counseling. It began simply as a settlement house in New York, and now serves more than 13,000 people living in East Harlem. Specifically in the 1990's, the Union Settlement Association was "selected to serve as the lead agency of the East Harlem HIV Care Network"; it "launched the Writing Through Reading Program" designed to aid adults in expanding their English skills; and it created the Youth Link Program, created to "work with drug-affected youth and young people involved in the justice system" ("Union Settlement"). Currently, in the 21st century, the association is continuing to provide needed services to the people of East Harlem in such forms as continuing the Writing Through Reading Program and providing spaces for local performers and benefits ("Union Settlement").

As more and more immigrants arrived, practically penniless, in America, the focus of the country, and its organizations, began to diverge from the Protestant white American to make way for a new racially diverse group. Social organizations became important centers for immigrants to converse and discuss their problems with other immigrants of the same culture. Social organizations like the Young Lords and Alice Kornegay’s Community Association of the East Harlem Triangle were vital in the survival of these immigrant groups who were struggling to stay afloat in a sea of hostility and prejudice. These organizations cushioned immigrants’ leap into the new and strange city of New York, and were what helped these culturally diverse groups of people to stay and make New York City what it is today: a melting pot.