Greenwich Village as a Historic District

From The Peopling of NYC

The Greenwich Village Historic District Extension consists of approximately 45 buildings that represent several phases of construction spanning nearly two centuries of development along Greenwich Village’s Hudson River waterfront, from 1819 to 2003. The architecture illustrates the area’s long history as a place of dwelling, industry, and commerce, and is a rare surviving example of this once typical development pattern on Manhattan’s west side waterfront. Seven buildings in the Historic District Extension date from the first period of development c. 1819-c. 1853, when Greenwich Village began to grow as people moved to the area to escape the crowding and epidemics of lower Manhattan.

The construction of the Hudson River Railroad (incorporated 1846) along West Street, helped spur commercial activity in this vicinity. After the Civil War, the population of the Historic District Extension changed as many middle-class families moved uptown and less well-to- do immigrants moved in, resulting in the conversion of single-family houses into multiple dwellings and the construction new tenements and apartment buildings. Three of the Historic District Extension’s most notable buildings were constructed to meet the needs of this growing residential population including the neo-Grec style Public School No. 7 of 1885-86 by David I. Stagg, the Victorian Gothic Revival St. Veronica’s Roman Catholic Church of 1890, 1902-03 by John J. Deery and the Renaissance-Revival-style former 9th Police Precinct Station House at 133-137 Charles Street of 1896-97 by John duFais. At the turn of the century, as the Hudson River surpassed the East River as the primary artery for maritime commerce, and the Gansevoort and Chelsea Piers (1894-1910) were constructed, West Street north of Christopher Street became the busiest section of New York’s commercial waterfront. The area of the Historic District Extension became the locus for a number of large storage warehouses, as well as transportation-related commerce, firms associated with food products, and associated industries.

After a period of decline, Greenwich Village was becoming known, prior to World War I, for its historic and picturesque qualities resulting in the conversion of tenement buildings in the Historic District Extension into middle-class apartments. The Historic District Extension attracted individuals involved in the arts. In 1961 Jane Jacobs, who lived in the vicinity of the Historic District Extension rallied neighborhood residents to oppose Mayor Robert Wagner’s plan to have the twelve blocks bounded by West, Christopher, Hudson, and West 11th Streets, and another two blocks along West Street south of Christopher Street declared an urban renewal site. The neighbors’ success, along with the publication of Jane Jacobs’ influential book The Death and Life of Great American Cities that same year established her as a renowned critic of urbanism. By the late 1960s-early 1970s the large warehouses of the Historic District Extension were being converted into apartments.

Today, the 45 buildings that comprise the Greenwich Village Historic District Extension represent a thriving neighborhood that illustrates nearly two centuries of development, from 1819 to 2003, that is a distinctive part of the history and character of Greenwich Village and its far western Hudson River waterfront section.

HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE GREENWICH VILLAGE HISTORIC DISTRICT EXTENSION

Contents |

Pre-Civil War Development

In the early seventeenth century, the area now known as the Far West Village was a Lenape encampment for fishing and planting known as Sapokanican. During Dutch rule, the second director general of New Amsterdam, Wouter van Twiller (1633-'37) “claimed” a huge area of land in and around Greenwich Village for his personal plantation, Bossen Bouwerie , where he cultivated tobacco. Starting in the 1640s, freed African slaves were granted and farmed parcels of land to the southeast of the historic district near current-day Washington Square and Minetta Lane and Thompson Street. Thus was established the African-Americans community that remained in this location until the Civil War. The actual area of the historic district, however, under British rule was amassed by Sir Peter Warren as part of a vast tract of land along the Hudson during the 1740s. In 1788, Richard Amos acquired the portion of the estate north of today’s Christopher Street, between Hudson and Washington Streets. Amos began to survey streets in 1796, and had subdivided the land into lots by 1817.

A number of cholera and yellow fever epidemics in lower Manhattan between 1799 and 1822 led to an influx of settlers in the Greenwich area, with the population quadrupling between 1825 and 1840. Previously undeveloped tracts of land were speculatively subdivided for the construction of town houses and rowhouses. By the 1820s and 30s, as commercial development and congestion increasingly disrupted and displaced New Yorkers living near City Hall Park,and the elite moved northward into Greenwich Village, particularly the area east of Sixth Avenue. Throughout the 19th century, Greenwich Village, including the area that is today the Greenwich Village Historic District, developed as a primarily residential precinct, with the usual accompanying institutions and commercial activities. The far western section of Greenwich Village developed with mixed uses, including residences, industry, and transportation- and maritime-related commerce.

A public Greenwich Market had existed since 1813 on the south side of Christopher Street between Greenwich and Washington Streets, on land formerly owned by Trinity Church. The market house was enlarged in 1819 and 1828, and the streetbed of Christopher Street was widened west of Greenwich Street to accommodate the market business and wagon traffic. Market business here was negatively affected by the 1833 opening of the Jefferson Market at Greenwich Lane (later Avenue) and Sixth Avenue, and the Greenwich Market was closed in 1835. The new market, also officially called the Greenwich Market but known as the “Weehawken Market” to differentiate it from the old market one block away on Christopher Street, was constructed in 1834, but only operated until 1844.

The earliest buildings located within the Greenwich Village Historic District Extension are six rowhouses.

Three activities just west of the Historic District Extension helped to spur commercial activity in the vicinity. Ferry service to Hoboken was re-instituted by 1841 at the foot of Christopher Street (earlier service, after 1799, was from the prison dock). Around 1845, part of the Newgate prison site was adapted for use as a brewery by Nash, Beadleston & Co. (later Beadleston & Woerz). In 1846, the Hudson River Railroad was incorporated, and was constructed along West Street, terminating in a station at Chambers Street in 1851 (this was replaced by the St. John’s Park Terminal for freight in 1868).

The Historic District Extension from the Civil War to 1912

A number of city-wide trends and nearby improvements affected the development of this area. After the Civil War, New York City flourished as the commercial and financial center of the country. In 1869, an elevated railroad line (the “el”) was completed along Greenwich Street, providing a rapid connection to lower Manhattan but also redirecting the development possibilities along the street. To the north of the Historic District Extension, roughly north of Horatio Street, a market district developed after the City’s creation of the Gansevoort Market (1879).

Two of the rowhouses in Historic District Extension were purchased after the Civil War and remained single-family homes into the late-19th century. Beginning just after the Civil War, numerous owners made improvements within the Historic District Extension. Reflecting the mixed-use character of the far western section of Greenwich Village, these included factories, stables, and multiple dwellings.

This section of Greenwich Village along the "el" was no longer a desirable location for single-family residences. Ten multiple dwellings, however, were constructed within the Historic District Extension over the course of two decades, in the Italianate, neo-Grec, and Renaissance Revival styles. Two stables buildings were erected in the 1890s The Hudson River waterfront was where the Gansevoort Piers (1894-1902) and Chelsea Piers (1902-10, with Warren & Wetmore) were constructed. These long docks accommodated the enormous trans- Atlantic steamships of the United States.

Beginning in the 1890s, the area of the Historic District Extension became the locus for a number of large storage warehouses, as well as transportation-related commerce, firms associated with food products, and assorted industries. The U.S. Appraisers Store (later U.S. Federal Building) was constructed by the U.S. Department of the Treasury as a warehouse for imported goods awaiting customs appraisal. Financier-brewer James Everard built the first of the warehouses in the Historic District Extension, an enormous 12-story, Romanesque Revival style structure which became known as the Everard Storage Warehouse and was identified by the large letters “EVERARD” in the cornices of both major facades. Everard’s daughter retained the property until 1934.

The Residential Component of the Historic District After World War I

After a period of decline, Greenwich Village was becoming known, prior to World War I, for its historic and picturesque qualities, its affordable housing, and the diversity of its population and social and political ideas. Many artists and writers, as well as tourists, were attracted to the Village. At the same time, as observed by museum curator Jan S. Ramirez, as early as 1914 a committee of Village property owners, merchants, social workers, and realtors had embarked on a campaign to combat the scruffy image the local bohemian populace had created for the community. Under the banner of the Greenwich Village Improvement Society and the Greenwich Village Rebuilding Corporation, this alliance of residents and businesses also rallied to arrest the district’s physical deterioration, their ultimate purpose was to reinstate higher- income-level families and young professionals in the Village to stimulate its economy. Shrewd realtors began to amass their holdings of dilapidated housing. These various factors and the increased desirability of the Village led to a real estate boom – “rents increased during the 1920s by 140 percent and in some cases by as much as 300 percent.” For example, according to Luther Harris, From the 1920s through the 1940s, the population of the Washington Square district changed dramatically. Although a group of New York’s elite remained until the 1930s, and some even later, most of their single-family homes were subdivided into flats, and most of the new apartment houses were designed with much smaller one- and two-bedroom units. New residents were mainly upper-middle-class, professional people, including many young married couples. They enjoyed the convenient location and Village atmosphere with its informality, its cultural heritage, and, for some, its bohemian associations.

The desirability of the far western section of Greenwich Village as a residential community by the late 1920s is exemplified by the beginning of the trend to convert tenement buildings to middle-class apartments in the Historic District Extension. One example is 273 West 10th Street, marketed to middle-class tenants who were listed in the New York Times between 1930 and 1940. A 1938 advertisement in the Times for an unfurnished apartment here touted “two light, airy rooms, kitchenette, open fireplace; completely modernized; $35.” The demolition of the Greenwich Street “el” around 1940 made streets in its vicinity more desirable for residential use. Two of the oldest buildings in the Historic District Extension returned to use as single-family houses.

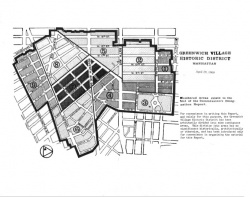

In 1961, Mayor Robert Wagner announced an urban renewal plan for the far western section of Greenwich Village that would have included the 12 blocks bounded by West, Christopher, Hudson, and West 11th Streets, and another two blocks along West Street, south of Christopher Street. As reported in the Times in March 1961,residents of the site immediately rallied in vigorous protest. That same year, Jane Jacobs authored the influential The Death and Life of Great American Cities. The urban renewal plan for this area was never to proceed as initially envisioned by the City. Jacobs, on behalf of the West Village Committee, wrote to the newly formed New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1963 (prior to the passage of the Landmarks Law in 1965 which enabled designations), urging that any consideration of a Greenwich Village historic district include the far western section of the Village to West Street. In 1966, the Commission designated as a Landmark the U.S. Appraisers Store (U.S. Federal Building) on Christopher Street. In 1969, the Greenwich Village Historic District was designated, with boundaries that included the contiguous blocks to the north and east of the Historic District Extension.

Commerce and Industry in the Historic District After World War I

The increased reliance on the automobile as a primary form of transportation after World War I was displayed in the Historic District Extension by the conversion of its stables buildings into garages, as well as the construction of low-scale utilitarian structures for trucking companies.

The completion of the Holland Tunnel (1919-27) and, especially, the elevated Miller Highway (1929-31) above West Street, providing easier access between the Hudson River waterfront and the metropolitan region, had a number of effects on real estate values in the area. The Federal Writers’ Project’s New York City Guide (1939) described the stretch of the waterfront along West Street, the “most lucrative water-front property in the world."

After 1960, with the introduction of containerized shipping and the accompanying need for

large facilities (space for which could be accommodated in Brooklyn and New Jersey), the

Manhattan waterfront rapidly declined as the center of New York’s maritime commerce. In addition, airplanes replaced ocean liners carrying passengers overseas. Most of the piers and many of the buildings associated with Manhattan’s Hudson River maritime history have been demolished.

1970s to the Present

By the late 1960s-early 1970s, the large buildings of the far western section of Greenwich

Village were ripe for re-use and conversion into apartments. As early as 1968-69, the Bell Telephone Laboratories, at West and Bank-Bethune Streets, northwest of the Historic District Extension, had been converted into Westbeth, a residential complex for artists.

In 1975, the New York Times mentioned that the “western fringe of Greenwich Village is one area where real-estate specialists expect a surge in conversions,” and by 1978, the Times described “a neighborhood in formation.”

Within the Historic District Extension, the two large Coffin-Sloane warehouse buildings at 1974-76 into the Towers Apartments. In 1974-78, the Everard Storage Warehouse building, was converted into the Shephard House apartments. No. 275 West 10th Street (1974-78, Bernard Rothzeid), a former garage that had been damaged in a fire, was converted into a residence on the same lot. No. 271 West 10th Street, a stables building, was converted into apartments in 1976, and No. 686-690 Greenwich Street had its third conversion, this time from a warehouse into apartments in 1977. The former 9th Police Precinct Station House building ceased to function as a police station after the construction of a new 6th Police Precinct Station House (1968-69), 229-235 West 10th Street, in the Greenwich Village Historic District. The station house, the prison, and the stable wing were converted into “Le Gendarme” Apartments by architects Hurley & Farinella. Nos. 708-712 Greenwich Street, warehouses, and the former stables building next door at No. 704-706 Greenwich Street, were combined onto one lot and converted in 1978-80 into apartments by Rothzeid, Kaiserman & Thomson. The first new buildings in the Historic District Extension since 1955 were No. 689, 691 and 693 Washington Street (1980-81, Peter Franzese), neo- Georgian style rowhouses. No. 692 Greenwich Street received a substantially altered facade in 1985 (Neil Robert Berzak, architect) when it was converted into apartments. Cardinal John J. O’Connor selected St. Veronica’s rectory, 657 Washington Street, to become a hospice for homeless AIDS patients in 1985. The owners of No. 134-136 Charles Street added an upper story in 1989 (Victor Caliandro, architect).

The Miller Elevated Highway, closed in 1974, was demolished in the 1980s because it had deteriorated and actually suffered a partial collapse. The buildings along West Street, formerly in the permanent shadow of the highway, were exposed again. West Street was suddenly attractive for residential development, including building conversion and demolition. Northwest of the Historic District Extension, the Manhattan Refrigerating Co. complex, West Street and Horatio-Gansevoort Streets, was renovated and converted as the West Coast Apartments and opened in the 1980s (the complex today is located within the Gansevoort Market Historic District). By 1999, the Times observed the Far West Village’s “developers’ gold rush” to convert structures and construct new high rises along the West Street corridor. The development retained the historic garage facade, though somewhat altered. The most recent structure built in the Historic District Extension was the Annex to the Village Community School, 278-280 West 10th Street (aka 663-665 Washington Street) (2000-03, Leo J. Blackman Architects). Designed to blend with the adjacent 1885-86 polychrome school, as well as to meet the cornice line of the adjacent multiple dwellings on Washington Street, the Annex building received awards for contextual design from the Historic Districts Council and the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. In March 2006, the Archdiocese of New York announced plans to convert St. Veronica’s into a chapel of Our Lady of Guadelupe/St. Bernard’s Church on West 14th Street. St. Veronica’s in later years had been serving as a mission of St. Bernard’s.

Today, the 45 buildings that comprise the Greenwich Village Historic District Extension, with its long history as a place of dwelling, industry, and commerce, represent a rare surviving example of this once-typical mixed-use development pattern along Manhattan’s west side waterfront. The architecture illustrates nearly two centuries of development, from 1819 to 2003, that is a distinctive part of the history and character of Greenwich Village and its far western Hudson River waterfront section.

| Historic District | |

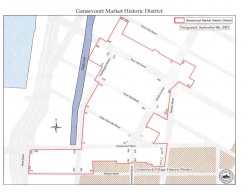

The Gansevoort Market Historic District CONDENSE The Gansevoort Market Historic District - consisting of 104 buildings - is distinctive for its architectural character which reflects the area's long history of continuous, varied use as a place of dwelling, industry, and commerce, particularly as a marketplace, and its urban layout. The buildings, most dating from the 1840s through the 1940s, represent four major phases of development, and include both purpose-built structures, designed in then-fashionable styles, and those later adapted for market use. Visual cohesion is provided to the streetscapes by the predominance of brick as a facade material. The street layout is shaped by the transition between the irregular pattern of northwestern Greenwich Village The earliest buildings in the historic district date from the period between 1840 and 1854, most built as rowhouses and town houses, several of which soon became very early working-class tenements. This mixed use, consisting of single-family houses, multiple dwellings, and industry was unusual for the period. After the Civil War, the area began to flourish commercially as New York City solidified its position as the financial center of the country, and construction resumed in the district in 1870. From the 1880s until World War II, wholesale produce, fruit, groceries, dairy products, eggs, specialty foods, and liquor (until Prohibition) were among the dominant businesses within the district in response to the adjacent markets, particularly along Gansevoort, Little West 12', and Washington Streets. The first of the two-story, purpose-built market buildings in the district were erected in 1880. Commercial construction during this period, which represents the highest percentage of the district's varied yet distinctive building stock, included not only low-rise purpose-built market buildings, but also, in a variety of period styles, stables buildings, and five- and six-story store-and-loft buildings and warehouses were constructed to house and serve these businesses. The warehouses, in particular, are among the most monumental structures in the district. The second factor spurring development within the historic district was the 1878 partition of real estate owned by the Astor family, which had remained underdeveloped since John Jacob Astor 1's acquisition in 1819. Of the 104 buildings in the district, over one-third of them were constructed by the Astors and related family members. TheGoelet family constructed the unusualflatiron-shaped store-and-loft building at 53-61 Gansevoort Street

Source: New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission Report on Greenwich Village