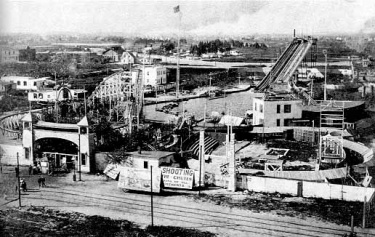

Coney Island History: Riding the Rollercoaster RailsFrom The Peopling of New York CityConey Island has had an extensive history of amusement parks. Through the years, the older residents of the area have had the fortune of riding the many rides scattered through these parks. The most well-known of these parks included Steeplechase Park, Luna Park, and Dreamland. Unfortunately, a string of bad fortune left most of these parks in ashes when they mysteriously caught fire and burned to the ground (at different periods of time, of course). Now, we can only

remininesce about the turn of the century, when we saw these parks at the height of their amusement business, when thousands and thousands of New York residents, as well as out-of-state residents, flocked to Coney Island for rest, relaxation, and cheap fun.

Source:Map of Coney Island in 1906 This map shows Coney Island in the year 1906. The blue lines help to outline the placement of the three of Coney Island's three most famous amusement parks of the time.

Sea Lion ParkThe Sea Lion Park was created by Paul Boyton as "the first outdoor amusement park in the world; one enclosed by a fence with an admission charged at the gate."[1] Historically speaking, it sat on 16-acres of land behind the Elephant Hotel. Two of the park's most famous rides were Shoot-the-Chutes and the Flip-Flap Railroad, both of which became incorporated into Luna Park when Sea Lion Park was torn down due to financial difficulties. According to Jeffrey Stanton, the Flip-Flap Railroad was "Coney Island's scariest ride." This was due to the fact that the ride consisted of "[t]wo-passenger roller coaster cars descending from a high lift hill and [sped] through a vertical 25 foot diameter loop. Its cars were held in place at the top by centrifugal force."[2] Because of such dangerous conditions, rides like the Flip-Flap "typically had more watchers then riders."[3] Those that did risk their lives on the Flip Flap usually received injuries. It "had a reputation for snapping rider's necks and was dismantled after it had ran a few years."[4] Though records of the rides and entertainment of Sea Lion Park are limited, other attractions that were housed here included Sea Lion Show, Cages of Wild Wolves, the Water Mill ride (also known as the Old Mill Ride), and Ballroom.[5] In the early 1900s, Boyton leased the park to Frederick Thompson and Skip Dundy, who were already in the amusement park business, as they were operators of the "Trip to the Moon" ride at Steeplechase.[6]

Steeplechase ParkSteeplechase Park was constructed in the 1890s by George C. Tilyou. When it was first built, the entrances to Steeplechase were grand in nature. They were constructed as arched entrances "topped with equine statuary."[7] The horse theme was created to go with Steeplechase's most famous ride of the time: "Gravity Steeplechase Race course, which was later renamed to "Steeplechase Ride." Tilyou tried to make Steeplechase somewhat exclusive by charging entrance fees, which was a good way to ensure that only people of certain status or of certain wealth could gain entrance. In 1907, Steeplechase was the victim of a fire and a huge portion of the park was destroyed, which put Steeplechase out of commission.[8] However, even from the ashes, Tilyou was able to keep his optimism of reconstructing the park, hoping to make it better and more grand in nature. He was aiming to be the best in the business. As the site lay in ruins, Tilyou used the time to charge "[10 cents] for admission to the burning ruins," which slowly helped him gain some money to put towards a reconstruction fund.[9] When Tilyou was able to rebuild, he added a new feature to his park, a glass dome-like structure that was created in order to allow for protection against foul weather. This ingenious addition to the park allowed Steeplechase to remain open in all types of weather conditions. According to Denson, the most popular rides in the park were those that allowed for some form of contact between the gameplayers.[10] As Bill Feigenbaum recollects: "The whole idea of Steeplechase was fun and sex. There was all that touching, hugging, falling down, bumping into each other, air ducts everywhere. When I worked at Steeplechase, I used to spend my whole lunch hour sitting in the audience watching the people coming off the horse ride. And I was surprised to discover how many girls didn't wear panties. I remember one woman - she must have been 250 pounds -- who did a little belly dance and had nothing on under her skirt."[11] Other notable rides and attractions at Steeplechase include: the Human Roulette Wheel, the Human Pool Table, the Trip to the Moon, the Pavilion of Fun, the Cave of Winds, the Airships Tower, the Ferris Wheel, the Human Zoo, the Aerial Slide, and the Steeplchase Pier.[12]

Luna Park: The Electric Eden Source: Library of Congress Collections Luna Park showing off its bright lights during the nighttime. Luna Park sits on the site of the former amusement park known as Sea Lion Park (see above). It was opened in 1902 by Fred Thompson and Skip Dundy, who were employees of Steeplechase at the time. Due to disagreements with their boss, George C. Tilyou, and the desire for more money, they left in hopes that owning an amusement park would be more worthwhile and profitable than just working in one. As they went, they took their Trip to the Moon ride along with them. They had originally created it, but was made famous because Tilyou brought it to Steeplechase, thus giving it a place in the public eye. It was reported that the ride was "jacked up on rollers and moved down Surf Avenue to the new park using elephants."[13] "Luna Park was an instant success," and it's majestic buildings of odd shapes and styles attracted many customers.[14] Though Luna Park was all newly constructed, Thompson and Dundy made the decision to keep some of the landmark rides of Sea Lion Park. These rides, including Shoot-the-Chutes and the Old Mill Ride, became some of the successful and memorable rides in Luna Park, so the owners' decision was right. The newly constructed rides and attractions were not too shabby either. Some notable ones included the Dragon's Gorge roller coaster, the Canals of Venice boat ride, the Miniature Rail (through a scenic Switzerland), the Trip to the North Pole, the Eskimo Village, the German Village, and the Chinese and Monkey Theaters.[15][16] As can be seen, a lot of the rides focused on travel and exploration of cultures around the world. The reasoning behind doing so is unknown, but perhaps it was a play towards the public's inquisitive side and curiosity. It is just as probable to assume that it might have had something to do with the astounding immigration numbers during the time. Luna Park was also notable for the Elephant rides that it offered the public, along with other wild animal exhibitions. And perhaps the one ride in the park that went with the sexual theme of amusement parks of the time was the Helter-Skelter ride. When the women rode down the long, winding slide, the men were waiting for them at the bottom for a chance to peek up their dresses. In 1911, the park switched hands from Thompson and Dundy to the Luna Amusement Company due to financial issues. It wasn't until the 1930s and 1940s that Luna Park had to officially close its doors after burning down in a series of bizarre fires.[17]  Source: http://www.westland.net/coneyisland/histmaps.htm Westland.net] This map shows Coney Island back in 1898 in an area known as West Brighton. It displays Coney Island between W. 10th Street and W. 5th Street down Surf Ave. On the left side of Surf Ave, one can see prominent names such as Charles Feltman (the creator of the Hot Dog) and C. Tilyou (the man that established Steeplechase. Around this general area, right under W. 10th Street, the site became the area of Dreamland.

DreamlandDreamland was built in 1904 by ex-Senator William Reynolds, "who sought to duplicate the success of Luna Park by copying its attractions on a grander scale." The one major ride that was duplicated by Reynolds in Dreamland was the Shoot-the-Chutes ride, which he extended right out into the ocean. So whereas Luna's Shoot-the-Chute ended with the boat gliding into an artificial lake, Dreamland's ended in open water. In fact, a lot of the rides and attractions in Dreamland were almost copied from Luna exactly, except bigger, such as the Canals of Venice and the wild animal exhibits. However, the park should be given credit to the new rides that it had to offer, including: the Under and Over the Sea ride, the Haunted Swing Illusion ride, the Circus Side Shows, Destruction of Pompeii, Hell Gate, and Lilliputia the Midget City.[18] Lilliputia was one of the odder and more unique attractions, which was "populated by three hundred little people."[19] It was essentially a makeshift town that was built especially for these "little people." As Stanton writes: "Everything was built in proportional scale of the inhabitants, from the theater to the beach lifeguard towers and toilets in their homes. The midgets had their own parliament, their own Midget City Fire Department that responded hourly to a false alarm, and their own beach complete with midget lifeguards. There was also a "Midget Theater", circus arena, miniature livery stable with diminutive horses, bantam chickens, and midget Chinese laundrymen."[20] However, Reynold's hopes were just not meant to be. When Dreamland was constructed, it was built on a very "symmetrical" design, it was "refined, orderly, and symmetrical with every classical building painted pristine white." This display was just not popular with the Coney Island visitors, compared the oddity of the look of Luna Park and Steeplechase.[21] The "centerpiece" of Dreamland was the Beacon Tower, which was made 375 foot tall to rival the towers and spires of Luna Park. It was in "Hell Gate" where a small fire broke out on May 27, 1911. It quickly spread throughout the park, and the park was ultimately burned to the ground. Since Dreamland was in the midst of exchanging hands and renovating at the time, there was just insufficient funds to put towards reconstructing the park.[22] As Koestler reports in Smithsonian Magazine: "Ironically, when this park also burned to the ground in 1911, it was the work not of Fighting the Flames but of light bulbs from a water ride."[23] Among the many amusement parks that Coney Island has been host to, Dreamland was the quickest to close its doors to the public.[24] Astroland Source: [http://www.stevespak.com/spak/pictures/coneyisland.html SteveSpak.com Astroland is the only remaining amusement park in Coney Island today. It’s street address is at 1000 Surf Avenue, Brooklyn NY 11224. The first season Astroland opened for business was the spring of 1962. The park currently sits on the former site of the famous Feltman’s restaurant, which was foreclosed in the early 1950s. [25] During the same time period, Fred Trump was buying up significant portions of Coney Island property to turn into housing projects. When Steeplechase Park went out of business in 1964, Trump bought the land on which it stood in hopes of building more housing buildings. However, due to zoning issues, he was unable to get a building permit on the area. Trump heard rumors of advocates trying to make Steeplechase a landmark, and out of frustration and inability to lose, he organized an event that led to the demolishing of the park.[26] When Feltman’s was closed, Dewey Albert and Herman Rapps were in the frontline to purchase the property before Trump in hopes of keeping a parcel of land that would remain part of the amusement industry. After much planning and discussing, it was decided to build a new amusement park on the land, which later became named Astroland, due to the “space race” that was occurring at the time.[27] The hopes of Astroland was to revitalize Coney Island and bring back the nostalgia of the turn of the century, when the amusement parks were at their peak.[28] Astroland encloses many landmark rides including the Parachute Jump, the Cyclone rollercoaster, and the Wonder Wheel. The Wonderland kiddie park came as an addition to the park after some time to allow for appropriate fun and games for the younger generation, who were probably the main target group of the amusement business. Towards the beginning years, new rides were constantly being added by many developers wishing to contribute to building of the last amusement park in Coney Island. Some of these builders were notable for their work the Disney parks such as Fred Pickard and Bill Campbell. Many of there contributions worked towards creating a futuristic scene in the park, such as the Mercury Capsule Skyride. Other Rides and AttractionsOther than the rides and attractions located within the different amusement parks, there were also many roller coasters and attractions that were seperate, but still along the general area. Some of these rides included the Cyclone Roller Coaster (which later became a part of Astroland), the Thunderbolt Roller Coaster, the B&B Carousel, the Bobs Roller Coaster (which later was renamed the Tornado), and the Iron Tower.[29][30] References

|