The Tumultuous 80s and BensonhurstFrom The Peopling of New York City

New York City: The Gilded 80s"By 1989, New York was a troubled city. The twin scourges of crack cocaine and AIDS were straining both law enforcement and health care resources past all reasonable limits. The gulf between the haves and the have-nots was wider than it had been nearly a century. While largely uncharted resentment and anger at unyielding social conditions seethed and bubbled in black neighborhoods, well-documented and often-tolerated loathing and fear of blacks grew in the city's white enclaves as homicide statistics rose in minority communities. The resulting animosity and tension between the races had grown to a fever pitch by that summer, to a point where lives were endangered and even lost."[1] In the 1980s, New York City experienced massive economic growth, becoming a global banking and financial center. However, underneath New York’s gilded exterior lay serious problems. After four decades of job loss in manufacturing, “New York City [continued] to lose blue-collar jobs twice as fast as the rest of the United States, with significant effects on its occupational and residential structure. As financial and business services [continued to grow,] the city’s income distribution [became] progressively polarized, inducing a growing schism between rich and poor.”[2] Crack cocaine became a major problem on the streets, stretching the police department’s resources paper-thin. The drug epidemic had serious fiscal consequences on the city with little to no positive effect; "despite the more than $500 million spent by the city in [1988] on drug-related enforcement alone - more than twice the amount in 1986 - . . . crack more than tripled the number of cocaine users in the city since 1986. According to New York State statistics, there were 182,000 regular cocaine users in New York City in 1986. That number grew . . . to an estimated total of 600,000 in 1988.”[3] With the drug epidemic came a surge in violent crimes. Statistics presented in the late 80s explained that "from 1987 to 1988, the number of murders in New York rose 10.4 percent” and that “drugs, . . . in particular crack, played a role in at least 38 percent of the 1,867 murders [in 1988].”[4]

The type of crime that was most feared by the general public in American cities in the late 1980's was random street violence, such as rape and robbery. Cases like the Central Park rape, where young black and Latino men were charged with raping and assaulting a white woman, made headlines and incited fear in primarily white communities. “Violence perpetrated against blacks because they were in an all-white neighborhood and ‘must be up to no good’ was seen as justified by the fear factor,” and although racially motivated crimes were not new to New York in the 80s, they “were being committed with startling frequency.”[5] Statistics from the late 80s show that 177 bias incidents were recorded in New York City in 1980, but that number had increased steadily to 541 in 1989.[6] Racial Unrest"New York is a powder keg right now, and it will take just a tiny spark to set it off."[7] While many of the bias incidents of the 80s passed under the radar, a few became infamous in what was a decade of festering racial unrest in New York City. Willie TurksThe Willie Turks murder was the first of several high-profile bias crimes in New York during the 1980s. On June 22, 1982, Turks, a black New York City transit worker, and two black co-workers were in the Gravesend section of Brooklyn. During a stop at a bodega, the men were confronted by a group of white men. In an attempt to avoid a conflict, Turks and his friends tried to get away when their car broke down. The mob of white men, which had grown to about 15 to 20 individuals, dragged Turks out of the car and fatally beat him with clubs and bats. Six men were eventually charged with Turks' death, and four of the six were convicted or pleaded guilty to the crime. Gino Bova, one of the four men convicted, was given the longest sentence of 5 to 15 years. During the sentencing, Judge Sybil Hart Kooper said, "There was a lynch mob on Avenue X that night. The only thing missing was a rope and a tree."[8] Howard Beach: The Turning PointOn December 19, 1986, Cedric Sandiford, Timothy Grimes, and Michael Griffith, three black men from East New York, were on their way to pick up Griffith's paycheck when their vehicle broke down in the Howard Beach section of Queens, a predominantly white working-class neighborhood. They were initially jeered by a group of white males, though the hecklers eventually dissipated. The situation, however, escalated when the group of whites, led by Jon Lester, returned with reinforcements and weapons. The mob immediately attacked the men; they brutally beat Griffith and Sandiford, while Grimes was able to escape with minor injuries. Gravely injured, Griffith, in a attempt to save his life, broke out in a run. In an effort to get away from the mob, he ran out onto the Belt Parkway where he was hit and instantly killed by oncoming traffic.[9] ReactionMost of the racially motivated murders of the 1980s were met with very little public reaction from New York's African-American community. Whatever small reactions occurred received very little public attention and created no real danger to public order. However, the Howard Beach incident changed all of that. When Cedric Sandiford escaped from the mob, he sought help from police officers who, instead of treating him like a victim, handled him like a suspected criminal. As a result, he sought the legal services of Alton Maddox, a lawyer known for his involvement in bias crime cases in the past. Maddox collaborated with Al Sharpton, a fiery activist who already knew how to attract media attention, and the two men worked together to bring the case into the spotlight. Maddox was able to get a special prosecutor, Charles J. Hynes, assigned to the case. Hynes, a capable trial lawyer, “obtained manslaughter indictments against Jason Ladone, Michael Pirone, Jon Lester, and Scott Kern," the men considered to be the ringleaders behind Griffith's death.[10] The defense attorney, Stephen Murphy, insisted the attacks were not racially motivated, causing some African-Americans to regard him as a racist, and some working-class whites to regard him as hero. At the end of the case, Hynes won three convictions. The case, however, had long-standing consequences. "Bitter reactions by blacks to the crime, the white community's apparent acceptance of the defense tactics, and white displeasure with the convictions won by prosecutors fed strong negative emotions that were already running like electricity through the streets of New York."[11] Tawana BrawleyIn November 1987, sixteen-year-old Tawana Brawley was found in a garbage bag with feces smeared on her face and racial slurs written all over her body. Brawley alleged that she was assaulted and raped by white police officers and a white assistant district attorney. Sharpton, along with Alton Maddox and another attorney, C. Vernon Mason, were hired to represent Brawley and her family. Almost immediately, however, Brawley’s story started to unravel. Physical evidence, as well as inconsistencies in her story, caused many people to think that Brawley had fabricated everything. At the same time, the team that Sharpton created led a loud and boisterous smear campaign, blatantly accusing prominent officials of racism. When a grand jury concluded that Brawley fabricated the rape, Sharpton’s credibility was immediately and visibly damaged. Many, including middle-class African Americans, were embarrassed by the turn of events of in the case.[12] The media also faced sharp criticism for what was perceived to be biased treatment toward’s Brawley. Benjamin L. Hooks, executive director of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People was recorded as saying, "We don't know what happened to Tawana Brawley, but we have been disturbed by the way the identity of a minor in a rape case was made known and sensationalized. One television station even ran a picture of her nude from the waist up."[13] It became clear in the summer of 1988 that there was a deep racial divide surrounding this case. New York’s white working-class communities were angry over what they perceived as the “Brawley hoax” propelled by Sharpton.[14] African-Americans began to feel that justice would only be served if they took to the streets and demanded it. A poll taken during June of that year showed a gap of 34 percentage points between blacks (51%) and whites (85%) on the question regarding whether or not Brawley was lying.[15] Central Park Rape

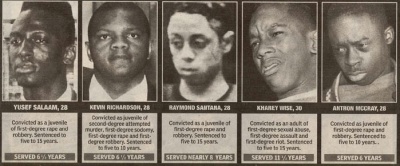

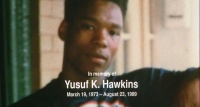

On April 19, 1989, a woman was jogging through Central Park when she was ambushed by a group of men. She was brutally beaten, raped and left for dead. She was only found hours later, barely clinging to life. The suspects charged for the crime were a group of young African-American and Latino men who, as police described at the time, were part of a larger group of about thirty that went on a criminal spree throughout Central Park that night.[16] Five teenagers, ranging in age from 14 to 16 years, were charged with the crime. Although there was no physical evidence linking them to the crime, their confessions were enough to convict the five young men to prison. There was no trace of the victim’s blood on any of the boys, despite the fact the victim lost three-quarters of her blood. Their confessions, which were recorded two days after the boys were brought in for questioning, were plagued with inconsistencies.[17] Their stories placed them at different times, different places, and contained different details. Despite the lack of evidence, the media had concluded the boys were the ones guilty for committing the crime, shaping public opinion.[18] In 2002, more than a decade since the young men were convicted, serial rapist Matias Reyes, already serving time for murder and rape, confessed to the crime. His confession was backed up by DNA evidence, and it was concluded that he acted alone.[19] The media, like in the Tawana Brawley case, once again came under fire. Black activists believed that the term “wilding,” a word commonly used by newspapers to describe the spree, drew unfair “feral connotations” to describe group violence when perpetrated by blacks, and not by whites.[20] The press was also accused of generating a media frenzy, polarizing the city even further. In an April 23, 1989 New York Post article, Pete Hamill wrote: They were coming downtown from a world of crack, welfare, guns, knives, indifference and ignorance. They were coming from a land with no fathers. . . . They were coming from the anarchic province of the poor. And driven by a collective fury, brimming with the rippling energies of youth, their minds teeming with the violent images of the streets and the movies, they had only one goal: to smash, hurt, rob, stomp, rape. The enemies were rich. The enemies were white. [21] Commentators connected the Central Park case to the Brawley case; they protested that "the same media that demanded Brawley "prove" her sexual assault made no such demands in the Central Park case.”[22] The perception in the black community was that there was an unbalanced value placed on white life in the media, while crimes committed against blacks was essentially unimportant.[23] Bensonhurst's Woes:The 1980sThe problems that plagued New York City in the 1980s were not unknown in Bensonhurst. Most of the people in the community were blue-collar workers, and it wasn’t uncommon for their children to follow in their footsteps. Like other working-class communities, Bensonhurst was extremely troubled by “substance abuse, shrinking career and employment opportunities, and an extremely high dropout rate.”[24] While the financial and business sectors prospered, young men entering the workforce had to the face the reality of a shrinking demand for blue-collar jobs. Disillusioned, many in the neighborhood looked towards blacks as the reason for their problems. Because the Marlboro Houses, low-income housing areas populated by African-Americans, were situated near the neighborhood, racial tension between Italians and African-Americans was already common; thus, the young men of Bensonhurst were quick to complain that blacks “take all the good jobs” and don’t do “anything except collect welfare.”[25] At the same time, organized crime's presence in the community only exacerbated conditions. Many of the young men looked towards alternative means of making money, and the mob provided a possible escape for their financial woes. Although many of stores in Bensonhurst were legitimate businesses, others were fronts for drug trafficking and gambling operations.[26] The presence of drugs in the community was most apparent when, in 1987, a makeshift cocaine lab exploded in a building on 1365 West Seventh Street; authorities "discovered more than 40 gallons of ether and candles burning inside one apartment.”[27] Territorial control was an extremely important concept in Bensonhurst. During the 80s, Bensonhurst was known for have some of the most notorious youth gangs in Brooklyn. These groups were extremely protective of their “turfs,” and they would “fight for their tiny fiefdoms with fists, feet, bats, knives, and even guns.”[28] One of these groups, known as the “schoolyard boys,” claimed their territory around Public School 205 on Twentieth Avenue, between Sixty-seventh and Sixty-eighth Street. In a neighborhood where the tough “wise guy” image was so apparent and admired, it was not uncommon for even the smallest of disputes to escalate and end in violence.[29] The people of Bensonhurst were noticing something very important about their neighborhood: It was changing. Immigrants were moving into the neighborhood, and they weren’t necessarily from Italy. Asian immigration into the neighborhood was steadily increasing, and the change was not always welcome. Tensions peaked when fliers were posted around the neighborhood accusing local real estate brokers of promoting an “Asian” invasion into the Italian enclave.[30] Though the tension declined over the years, it never fully disappeared. The people of Bensonhurst were aware of their economic problems, and those feelings were worsened by their changing surroundings and the racial tension that permeated New York in the 80s. The tribulations faced by the people of Bensonhurst and the pent up frustration that occurred as a result culminated in one of the most publicized bias crimes in the history of New York. Yusuf HawkinsEvents prior to the murderPrior to the Yusuf Hawkin’s murder, tensions in Bensonhurst were reaching a boiling point. Gina Feliciano, a troubled girl in the neighborhood infamous for her drug problems, was having a spat with another Bensonhurst resident, Keith Mondello. The tension between the two began to grow because Keith, like many in the neighborhood, disapproved of Gina’s practice of bringing young black and Latino men to the neighborhood. On August 21, Gina and her friends, mostly young Hispanic men, were outside a local bodega playing loud music and, as some residents later recalled, smoking crack.[31] Keith and Gina had a heated argument where he told her to “stop bringing those niggers and spics around [the neighborhood] or there’s going to be trouble.”[32]Gina, livid, told people in the neighborhood that on her 18th birthday she was going to get her black and Hispanic friends to come down to Bensonhurst to “beat the [expletive] out of all of [them].”[33] Word spread quickly, and Keith Mondello, the primary target of the threats, decided to get as many people behind him as possible. That Wednesday, the 23rd of August, a crowd of young men steadily grew in the schoolyard of P.S. 205. Anticipation grew as more and more people arrived, some wielding bats, ready to protect their turf from intrusion. At the same time, Yusuf Hawkins and his friends, Troy Banner, Luther Sylvester, and Claude Stanford, were on their way to Bensonhurst. Claude had discovered an advertisement for a 1983 Pontiac, and he wanted his friends to go with him to take a look. They took the N train to the Twentieth Avenue and Sixty-fifth Street, where they got off in search of the car.[34] It was only when they got to Twentieth Avenue and Bay Ridge Avenue, two blocks away from the schoolyard, did they realize something was wrong. The ShootingThat night, anxiety and excitement swelled to a fever pitch in the schoolyard. When Yusuf and his friends passed the entrance to P.S. 205, they were spotted by the mob of white youths who quickly went to investigate. Keith Mondello and another young man from the neighborhood, Charlie Stressler, were ahead of the pack as the group of 30 surrounded Hawkins and his friends. Realizing that the four young black men were not Gina’s friends, Stressler and Mondello backed away, refusing to attack them. An excited figure, later identified as Joseph Fama, pushed ahead of the pack shouting, “To hell with beating them up. I’m gonna shoot the nigger!” He pulled out a .32-caliber revolver and fired four quick shots into Yusuf’s chest.[35]A woman from the neighborhood, Elizabeth Galarza, ran towards Yusuf as the mob scattered. She held his hand until paramedics Pericles Leonardis and Ralph Fasano arrived on the scene. Yusuf was taken to Maimonedes Hospital, where he was pronounced dead. The AftermathArrests and ConvictionsImmediately after the murder, Moses Stewart, Yusuf’s father, demanded that anyone who was part of the mob that night be charged with murder. He collaborated with Sharpton to get the media to concentrate on what happened to his son. Public pressure, as well as political aspirations, led Brooklyn District Attorney Elizabeth Holtzman to invoke the “acting in concert” legal principle. In other words, anyone who was there that night wielding a weapon was as much responsible for the murder as the gunman. Ultimately, only a handful of people were charged from a group of about 30. Prosecution of the entire mob would have been difficult, and their testimony was vital to convict those considered to be the key players. Keith Mondello, the ringleader, and Joey Fama, the shooter, were the only ones who served jail time; the others charged were either acquitted or assigned community service. Attorney Jacob Evseroff argued, "nobody was ever shot with a baseball bat."[36] This logic presented a compelling argument against the “acting in concert” principle. MarchesThat Saturday, Sharpton organized a march to be held through Bensonhurst. Almost 400 marchers came together for the demonstration. Shop owners in Bensonhurst closed down their stores, fearing that the march would escalate into a full blown riot. When the marchers got off their buses, Shaprton, Moses Stewart, and Yusuf's brothers lead the march hand in hand. The police presence was immediately apparent; there were mounted units, motorcycle cops, and plainclothes officers intermingled with the angry white crowds forming along Twentieth Avenue. The goal was to keep the two groups away from each other. The marchers chanted “Yusuf, Yusuf” as they made their way down the streets. The crowds watching from the side responded with their own chants of “Niggers go home,” while others spat and cursed. There were several tense moments during the march, especially when a man broke through the police lines; he was quickly removed. The demonstration ended at the 62nd Precinct on Bath Avenue, where the demonstrators returned to their buses.[37] On September 2nd, Sharpton organized another march. This time, he was planning on marching down 18th Avenue, where the annual Feast of Santa Rosalia was being held. Many in the neighborhood saw this further intrusion into their community by Sharpton as a shameless publicity stunt; a fourteen year old explained: "Look. Sharpton has to make money for his cause. So this shooting happened here, and now he comes and gets on television, and he makes more money for his cause. It's very simple."[38] The route, however, was altered when intelligence revealed that someone was planning to throw boiling zeppole grease on the marchers. Once the protest was underway, verbal abuse escalated on both sides. Riot police had a hard time keeping the two groups apart when people broke past police lines. Near the end of the march on the corner of Twenty-first Avenue and Sixty-eighth Street, a group of 40 kids tried to stop the buses from leaving. A police officer at the scene confronted the young mob: "What the [expletive] is the matter with you guys? I don't understand you! First you don't want them here. Now you don't want them to leave! C'mon, get up. I live here too, you know, and you're making me look bad and you look bad, and the whole neighborhood."[39] The march had devastating effects. At the time of the march it could still be debated whether or not Yusuf’s murder was racially motivated. Bensonhurst's response to the march, however, uncovered the frustration and prejudice festering within the neighborhood.[40] Bensonhurst's image was publicly tarnished, and the neighborhood came under attack from the media and politicians. However, it is important to note that marches held by other organizations did not get the same response from the people of Bensonhurst. Many blamed the magnitude of the response on Sharpton's presence. His reputation made him an extremely polarizing figure in New York. When a handful of white supremacists marched through Bensonhurst shouting slogans of praise, people in the neighborhood were more than unhappy. When the marchers piled into their van, a group of youths surrounded the van before a police escort was able to clear a path for it. One youngster muttered, "Nazi [expletive], I woulda liked to had a piece of 'em. [Expletive] racists and troublemakers."[41] References

|