ImmigrationFrom The Peopling of New York City: HarlemImmigration

Government Never Stays the Same In Harlem!New York was first founded as Fort Amsterdam and then later named New Amsterdam. On May 27, 1647, Peter Stuyvesant was elected as director general and ruled as a member of the Dutch Reformed Church. He reduced the city's religious freedoms and closed all of the city's taverns. The colony was given self-government in 1652 and New Amsterdam became a city in February 2, 1653. In 1664 England conquered the area and renamed it "New York" after the Duke of York. The English rulers of the previously Dutch New Amsterdam and New Netherland renamed the settlement as the City of New York. As the colony grew and prospered, the need for greater self-government also grew. During the Glorious Revolution in England, Jacob Leisler controlled the city and surrounding areas from 1689-1691, before being arrested and executed. The rebellion revealed class differences and some see it as a forerunner of the American Revolution. British occupation lasted until November 25, 1783. George Washington victoriously returned to the city that day, while the last British forces were leaving. The Congress met in New York City under the Articles of Confederation, making it the first capital of the United States. New York City remained the capital of the U.S. until 1790. New York expanded into an economic center, with the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825, which connected the Atlantic port to the huge agricultural markets of the North America. Immigration increased and a new street grid system expanded to encompass all of Manhattan. After the Revolutionary War thousands of mostly New England Yankees moved into the city. Their numbers were so large that by 1820, the city had far outstripped its pre-War population, was largely middle class with a growing upper-class, and was fully 95% of American born heritage. By 1850, the Irish comprised one quarter of the city's population due to the Potato Famine. Government institutions, including the New York City Police Department and the public schools, were established in the 1840s and 1850s to growing population residents. During the 19th century, the city was changed by immigration, a development proposal called the Commissioners' Plan of 1811, which expanded the city street grid to include all of Manhattan. During the American Civil War (1861–1865), the city's strong commercial ties to the South and irritation about conscription led to divided empathy for both the Union and Confederacy, turning into the Draft Riots of 1863. The new European immigration brought more social disorder. Old world criminal societies rapidly exploited the already corrupt municipal machine politics of Tammany Hall. In a city of tenements filled with cheap foreign labor from dozens of nations, the city was a source of revolution, racketeering, and unionization. [1] Religions of Ye Olde HarlemThe "official" religion of Harlem was Dutch Reformed. The first people attending worship did so in what is now the Marble Collegiate Church. In spite of this, the most prevalent religious identity in New Amsterdam wasn’t Dutch Reformed but French Huguenot (about a fifth of the population). No other religion was formally recognized until the "Flushing Remonstrance" which recognized the right of Quakers (and all others) to worship. When the first Jews arrived, Stuyvesant first wanted to deport them. He was overruled on this, however, and the first synagogue was formed. The ensuing English colony of New York was even less tolerant. While it had many churches, Trinity Church had official status, and was given great advantage over others. Also, following the English Civil War, Roman Catholicism was banned in colonial New York. Worshipers had to wait for a Jesuit spy to arrive to hold masses in an attic on Wall Street secretly. Catholicism was only legalized in the wake of the American Revolution when the first congregation formed in 1785. Afterwards, New York, and Harlem, was considered tolerant of all religions. [2] The Village of HarlemHarlem had originally been a small, detached agricultural community. Then, in the late 1700s, New York City’s wealthy citizens began to regard it as an ideal location for their estates. Later, Harlem was considered a suburb of the central city. By the early 1800s, the soil no longer supported agriculture, and many families moved to better lands. Some Black slaves lived in Harlem as early as 1752. Once free, many continued to work as servants in Harlem. The Village of Harlem was annexed to the rest of New York in 1873. Following the “Draft Riots” of 1865, in which Blacks were a target of aggression, many Blacks moved from Manhattan to Brooklyn. Still, thousands of Black families remained in shanties and tenements in the Harlem area. [3] Late 18 Century: Irish Squatters Over HarlemThe property value of the little ville in what is now Harlem had been viciously corroded under the occupancy of the Irish who paid not for their homes. Fortunatly for realestate agents, should they have existed at the time, the emaciated town was annexed to the city of New York in 1873. [4] Harlem Moves on UpThe village of Harlem received a package of an innate economic stimulous when city officials called for the construction of the paramount elevated railroad in connection to the rest of novel New York. The investment was the manifest hypothesis of several urban planners who believed that a Lexington Avenue Subway Line would ameliorate transportation to lower Manhattan. Harlem, with barely ten years to its name, is put under metal and hammer, and across its vegitative earthy face rises scars of metal: “the els.” Apathetic landlords rush to have their buildings complete before the boding housing regulations of 1901 are enacted, and after facilitating travel for commuters throughout the extension of the city railroad system, Harlem is rapidly transformed from a mute getaway for socially outcasted hermit families to an urbanized landscape of paint-fresh townhouses, apartments, and tenements; thus, birthing the Harlemite socioeconomic caste system that plagues the consciousness of primarily low estate residences in the area to this day. [5] Shalom Harlem!The construction race was radically uneven when the building of residence projects far surpassed that of the subway stystem. Real estate prices fell again attracting Eastern European Jews in the largest of numbers reaching a pinnicle in 1917 with a population of 150,000, a third of the modern day population of Statin Island. They hardly received a warm welcome; rental signs excluding Jewish customers were not considered racist and had been used ardently. Fifteen years later, the Jewish population was reduced to 5,000; the other 145,000 had moved through modern day Yonkers. [6] Ciao mio Bambino Harlem!Antes del Bario, or before it was Spanish Harlem, and after it was Little Africa, East Harlem was an Italian community whose rich neighbors were quietly ashamed of; New Italians were made to worship in the basement of their churches even though they had actually been the first new immigrants of the land since their arrival in 1870. Discrimination was adapted into the lifestyle and became an accepted frame of mind; meanwhile, the Italians responded with bitterness in fear of losing their cultural and economic dominance of the middle class when Asians began immigrating in the early 20th century. African American Entrepreneur Paves Way for Harlem’s African American InfluxThere were very few Blacks in 19th century Harlem. What is now Lincoln Center and was then San Juan Hill, contained a crowded population of Blacks who anxiously pursued the vacant tenements in Harlem after the collapse of the housing boom in 1905. Besides more space, they also moved in fear for their lives after the bloody riots in both Black concentrated neighborhoods of San Juan Hill and the Tenderloin districts. A housing realtor, Philip Payton, Jr., organized the Afro-American Reality Company dedicated to assist his fellows in renting or buying exclusively in the area. Feelings of naitivism and profound ignorance gave way to more prejudice in the uptown community. Founder of the Harlem Property Owners’ Improvements Corporation, John Taylor, was quoted saying “Drive them [Blacks] out, and send them to the slums where they belong.” Racist landlords made pacts against unassuming Black customers and Payton’s Reality Company would retaliate by buying more property and evicting whites in the process. As Blacks moved in, white residences moved out; between 1920 and 1930, 118,792 people who were white left the neighborhood and 87,417 Blacks arrived. By 1914 50,000 Blacks called Harlem home, and they were serviced by churches for Blacks and such racially designated YMCAs. By 1920, central Harlem was 32.43% Black. The census only one decade later revealed that 70.18% of Central Harlem's residents were Black and lived as far south as Central Park at 110th Street. [7] [8] Black Busting Busts A Prejudice Housing ScamUnwillingness of landlords in the rest of New York monopolized the housing in Harlem, allowing for racial exploitation. In the 1920s, a typical white working-class family in New York paid $6.67 per month per room, while Blacks in Harlem paid $9.50 for the same space. The accomodations were allowed to steadily decline in an inverse function with the desperation of the renter, an ugly pattern that lasted consistently through New York history for four decades until the invention of ‘Black busting’ in which a single property on a block would be acquired and then advertised for a very affordable rate with great publicity. Surrounding landowners were sent into a mad panic, and then speculators would buy additional houses relatively affordable and made so for Blacks. [9] [10]

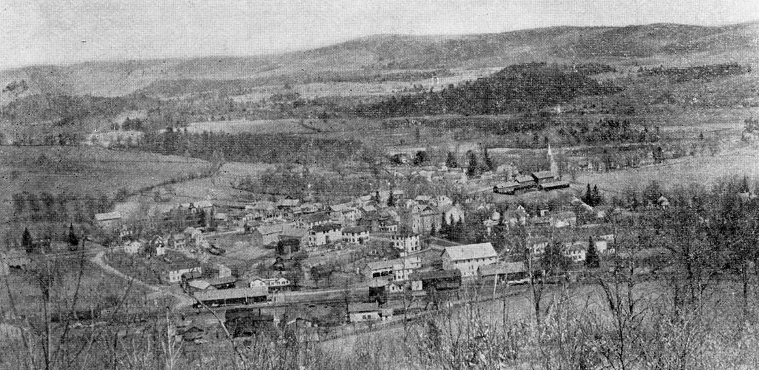

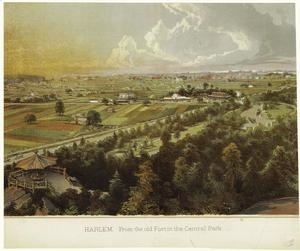

The Harlem We All Know but Hardly Exists StillThe 1960 census showed only 51% of housing in Harlem to be "sound," as opposed to the 85% of the rest of New York City.Thousands of weekly complaints were received by the New York City Buildings Department that complained about falling plaster, lack of heat, and unsanitary plumbing. Harlem of today has visited a world class dermatologist and has received a major facelift. Changing federal and city policies, crime fighting, and develpoing retail lane 125th street produced a rapid gentrification effect since the late 1990s. The Upper Manhattan Empowerment Zone funneled money into new developments, giving rise to chains and stops that Harlem had never seen before. The townhouses of last century are being sold for $ 1 million as of 2007. [11] Union Settlement AssociationThe Union Settlement Association is an institution in Harlem, which provides recent immigrants to New York with the support services they need to reach their goals. This includes learning English, earning a GED, helping to prepare taxes, and even childcare. Established in 1895, The Union Settlement has expanded since then, and has numerous locations in Manhattan. The programs they offer provide a safe afterschool environment for the kids in Harlem, as well as HIV support center and senior services. Harlem is definitely a community, not just a place, and this is proven by the Union Settlement Association and the efforts they make to unite the people of Harlem. Our class had the privilege to meet with some of the GED students from the Union Settlement, who came to Lehman College. We found out that many of them did not live in Harlem, but throughout New York City, which just goes to show how influential a community center in Harlem can be for the overall health of an area as vast as the five boroughs. Ruth Barral notes

|