The Ninth Street DilemmaFrom The Peopling of New York CityAnd now, Let's Walk through time, into the ancient history of east 9th street.

East Ninth Street

Walking in the Village WonderlandThe cozy buildings towered over me as I walked down the moon lit street. A canopy of Christmas lights were strung overhead, and behind the pale white sky, they twinkled like stars. The snowfall obscured my vision, but the bright storefront displays pierced through the haze. Fabrics, trinkets, foods, clothes and toys were floating in the white cloud that had consumed my home. My young eyes peered into an ancient world, yet still so vibrant with life that the very streets were being painted by its residents. As I neared my apartment building, I looked back, considering the lactescent sky where looming skyscrapers would soon be visible. The memories of my imagination still resonate most strongly with my memories of living on 340 east 9th street. Those skyscraper-conspirators finally made their way to my apartment, evicting my family on unfulfilled claims of “owner occupancy”. So the dream was shattered as quickly as new residents took hold of the neighborhood, as the very face of the place was lost to a new rush of people. However, I did not fail to consider myself in a larger context. “What rush was I a part of?” I had obviously not lived in the place for the entirety of its existence; the buildings I saw around me must have dated back to the early 20th century. Thus, my home and my experience being forced out of it could only be a modern replication of the same passage earlier generations set upon. In the heart of the east village, there was an old culture that I still felt resonate about the place through out my child hood. There was a community separate from the rest of New York, old entrepreneurs mixed with drug addicts, and musicians still held in balance for on lookers to consider both the old and new history of the area. However, the crowds those musicians brought soon out dealt the old men, and the drug addicts faded as Giuliani’s militant tactics cleaned up the city. In the wake of it all, the streets were repaved, the paints of self-expression washed away. Curiously though, when I walk down 9th street, the block between first and Second Avenue cozily sits below the height of a fire fighter ladder, and the Christmas lights still go up every year. When it is snowing, you can almost see the brown paint pealing and my old blue building taking form in its wake. ¬ The ArchitectureIronically, the architectural design of the street has remained intact since the tenement developments of the early 20th century. Some new buildings have been constructed, such as the low rise building 320 East 9th street, constructed in 1980. The Architecture has some striking differences, however, the main aesthetic appeal of the block is not shadowed by this seven story building, matching its short tenement brethren. Like, for example, the tenement 312 east 9th street constructed in 1900.

The Tenements

"Ssc 68 Windows in rooms: In every tenement house hereafter erected the total window area in each room except water closet compartments and bathrooms shall be at least one tenth of the superficial area of the room [8] While imposing the implementation of windows in every room, the railroad style apartment offered little fresh air for the dark middle rooms. Before that, there existed no state or federal laws, giving land owners free reign over their constructions. The new law stated that for every 20 tenants an outhouse or privy, connected to the sewers if possible, was to be provided. Also, transoms were to be constructed in the inner rooms. Unfortunately, these meager parameters were unenforced: it wasn’t until the Tenement House Act of 1901 that any real improvements were made. [9] The law, enacted in 1879, required a toilet installation for every two families. Each apartment was to have proper ventilation and window access. However, many of the tenements built violated the law. As reported in The Tenement House Problem, "the law since 1879 has required that every living room in a tenement house thereafter erected should have a window opening directly to the outer air it is apparent that these buildings have for more than twenty years been violating fundamental sanitary rules." [10] The Tenement House Department was designated to inspect all houses to ensure the requirements were met. After inspecting the tenement owned Kate Moeschen, the department ordered her to improve the sanitary conditions of the building. She sued on the grounds that the law was unconstitutional, but the law was upheld in the supreme court.[11] All the pre-war buildings on 9th street follow the basic design set by the Tenement House Act of 1901, and have been adapted for modern use.[12] In fact, many of the buildings surrounding my own had back yards, presumably the location of the public privies. So waste dump became a backyard luxury. Jacob Riss, the 19th and early 20th century social activist of the lower east side, documented the state of tenement housing and its peoples in his two books, How the Other Half Lives and The Battle with the Slums. While considering the layout and construction of the tenements architectural design he writes, “Bedrooms in tenements were dark closets, utterly without ventilation. There couldn’t be any. The houses were built like huge square boxes… Forty thousand windows, cut by the Health board that first year, gave us a daylight view of the slum: ‘damp and rotten and dark, walls and banisters sticky with constant moisture…’ forbid the putting of a house five stories high, or six, on a twenty-five foot lot, unless at least thirty-five percent of the lot be reserved for the sunlight.” [13] A similar report was given by the Citizens Council of Hygiene in 1866. While considering the cholera epidemic, they noted the quality of tenement construction and life. They wrote, “Not only does filth, overcrowding, lack of privacy and domesticity, lack of ventilation and lighting, and the absence of supervision and of sanitary regulation still characterize the greater number of the tenements; but they are built to a greater height in stories; there are more rear houses built back to back with other buildings, correspondingly situated on parallel streets; the courts and alleys are more greedily encroached upon and narrowed in unventilated, unlighted, damp, and well-like holes between the many-storied front and rear tenements; and more… are created as the demand for the humble homes of the laboring poor increases.” [14] Through their efforts, and the court rulings favoring tenants, the apartment owners were slowly forced to maintain basic sanitary conditions for their residents homes. The quality of life on the lower east side began to improve. However, those improvements, along with external developments, began a new trend of real estate speculation. Instead of profiting off the mass of poor immigrants, an opportunity to develop upper middle class and rich housing began to present itself. There were several attempts to reconstruct the Lower East Side to accommodate the rich at the turn of the century. For example, Samuel Ageloff was prepared to "'Stake his fortune in helping rebuild the East Side.'" [15] He began the construction of a 2.5 million dollar building on 10th street and avenue A. However, upon the onset of the Great Depression, the 50 dollar per month rent fee was an impossible charge. As a result, he jumped off his own towers. Thus, the tenement state of the Lower East Side remained as monetary means were inaccessible. At the same time, the vacancy rate increased to 14% by 1928 [16] These desires to develop, compounded with vacancy rates, were finally able to surface when the economy boomed in the 1950s. However, the striking attachment the residents held for their neighborhood maintained, and thwarted most large scale development plans all the way up until the second economic collapse of the 1970s. [17] The DevelopmentThe Initial industry that fueled the development of population in the East Village was the profitable ship building industry. In the early 1800s, the East River provided better shelter from the winter weather hazards. Developments in transatlantic expedited the businesses, increasing the demand for migrant workers. [18] Other industries tied to ship building, such as iron working, fostered as well, only increasing demand for labor. The Irish settled mostly around five points, whereas the Germans, already north of them, expanded up into the East Village during the 1840s [19]. During this time, the tenement development surged, with over 1,200 tenements built By the 1850s, however, iron hulled steam ship development depreciated the original ship building industry. Since the larger ships were better able to dock on in the Hudson river on the west side, soon to did the East Village docking area loose its hold as the main docking port.[20]. The population decline of Europeans.[21] : "Take the Second Avenue Elevated and ride up half a mile through the sweater's district. Every open window of the big tenements, that stand like a continuous brick wall on both sides of the way, gives you a glimpse of one of these shpos as the train speeds by. Men and women bending over their machines or ironing clothes at the window, half naked... The road is like a big gangway through an endless workroom where vast multitudes are forever laboring. Morning, noon, or night, it makes no difference; the scene is always the same. [23] The industry was booming; New York City accounted for over two thirds of the total United States production of women's clothing for 1900. [24]. However, as the century plodded on into the 20th century, the industry began to diminish. The Immigrant restriction laws of 1917 and 1921 blocked the flow of cheap labor into the East Village. The newly developed highway systems allowed manufacturing to take place in cheaper rural areas, reducing the value of New York based production. Finally, the onset on the depression encouraged cheaper, mass produced clothing. [25] The People Image of the Queen of the Boys Club in 1949[26] The first wave of mass population to characterize the neighborhood met with conflict from the encroaching group of a younger generation, facing what would become a similar conflict as my own eviction. The conservative Slavic of the earliest generation considered their new arrivals with negative scrutiny; their garish stores with oddities and fur coats challenged the uniforms of their traditions. However, such stores like the 9th street bakery still remain today. Better yet, one Mrs. Ernie Garcia, whose husband had made custom shirts since the late forties, reported she “personally likes [the new comers], though a lot of old timers don’t. I think it’s interesting, but I’m artistic, and I like to look at artistic things. And I have a son who wears his hair long so I have to be understanding.” [27] The ties between communism and the artistic were deeply ingrained in the media at the time, 1969. The older cold war generation debased the ideals of the young, however, such political ideals were not a new thing for the area. The WPA Guide to New York City , published in 1939, describes the area as a composition of Italians, Slavs, Russians, and East European Jews. The guide states, "Politically, the colony is violently divided between pro- and anti-Soviet. [28] Although many of the traditional European groups may not have shared a connection to the trendy developments of the East Village, the socialistic ideological battle was rooted well before the counter-culture generation. Quite a few of the victims of the SS General Slocum accident held residence in the east village, more specifically, there were several people who had taken residence on 9th street between first and second avenue. Among them include: Mrs. Lizzie Kopf, and Ellis of 337 east 9th street, Jonk, Bertha of 314 east 9th street, Horway, Carl of 313 9th street and his family Delia, Johanna, Courtlandt Horway and Ohl, Carl. [29] Mrs. Lizzie Kopf was of German descent, and 32 two years of age, having lost her child Ellis in the accident with her. [30] According to the WPA Guide to New York City , the tragedy of the event marked the end of the German dominance of the Neighborhood, who, stricken with grief, moved to other parts of the city. [31] The local sect of the Boys’ Club of New York, the Harriman Clubhouse, served to house thousands of lower east side children, some of whom lived on 9th street. Over all, however, the Club continues to operate and house over 1,500 boys per year. [32] One such member was 340 east 9th street resident Peter Berkey and his sister Victoria who won the Little Sister Beauty pageant and titled queen of the Boys Club in 1949.[33]

340 East 9th StreetHaving lived in the apartment building, I was especially interested in throughly researching the people who lived in 340 East 9th Street. Unfortunately, none of the people who lived in the complex were incredibly famous, forcing me to search for them through census data. Even more troubling was the fact that the census data available, the 1890 Police Census, provided a limited understanding of the residents who lived there. It merely listed their name, age, and sex. Even at that, some of the surnames were obscured. Based on that limited preview, most of the names seemed to be tied to German and Irish descent. However, a wider perspective of a few traceable names was revealed with the use of the Ancestry.com data base.

The Johnston Family: Although the family is reported to have lived in 340 East 9th street in the Police Census record, the Twelfth Federal Census names an illegible location, which is presumably different. In that census, however, William, the head of the family, was born in New York in 1862. His parents were both of German descent. He was a musician, who could read write and speak English. He rented his apartment. His wife, to whom he had been married 13 years in 1900, was born a year later as a descendant of two Irish parents. She, like her children, were all literate and English speaking. The couple had three children, two sons and one daughter. The sons were two years apart in age, the first born in 1888 and the second in 1890. They were both enrolled in school. The daughter was youngest born in 1895. William had an incredibly popular name, and as such, it was difficult to isolate his death. However, I managed to isolate it to somewhere between 57-62. His son was also difficult to place, but I found two deaths that match his birth year, one in 1912 at the age of 23 and the other in 1948 at the age of 59. Based on the literacy and occupation of William, I would assume the latter considering they most have shared a level of opulence that might have sparred them the strife of poverty. The Becker Family: According to the Twelfth Federal Census, John Becker continued to live in 340 East 9th street ten years after he was documented living there in the Police Census of 1890. He was fully German on both his mother and father's side, but born in New York in 1855. Interestingly enough, he was not the textile worker nor the day laborer that seemed all too popular for the average tenement worker. Instead, he was a painter. He had no months of unemployment and could read write and speak English. He also was the owner of his home. He had a wife of 20 years named Amelia and three daughters, all of whom were able to speak English. They could all read and write too, except the youngest three year old daughter Ruth. Helen, at the age of 12, was enrolled at school. The eldest, Amelia, was 19, but had not attended any school. According to the Department of Records held in the municipal archives, John Sr. presumably died in 1917, at the age of 62 with the certificate number 18296. His wife would join him over a decade later, at the age of 74 in 1932 with the certificate number 14072. There were no other traceable names from the Police Census data, however, there were some accompanying names with the Becker family in the Federal census data. All of which were of either German or Irish descent. Also, all of the neighboring children were enrolled in school, and besides one Foreman, which is already in the field of skilled labor, the rest of the working residents held middle class jobs such as bookkeeping, sales and printing. From the beginnings of the lots development it would seem 9th street did not house the immigrant and utterly destitute population that resided in many of the other parts of the neighborhood. References

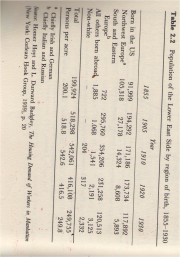

|