User:StariqFrom The Peopling of New York City

BiographyHi, my name is Sara Tariq, I am in the BA/MD program and plan to major in psychology here at Brooklyn College. I chose to be a part of Macaulay Honors College because it would give me the opportunity to learn more about New York since I have never lived here before. I am from Cedarhurst, Long Island and have lived there most of my life. I graduated from Lawrence High School. Some of my hobbies include going to Broadway shows, reading, traveling, shopping and playing some sports. My favorite sport to both watch and play is probably tennis but I like other sports as well. In high school, I was involved in several community service clubs, the school newspaper and the school yearbook, the Lawrencian. The best class I took in high school was definitely art history because this not only exposed me to the major art movements, but allowed me to appreciate art in a whole new way. I live with my parents, my brother and sister and since most of my extended family is in Pakistan, we travel to Pakistan almost every summer. Class AssignmentsIdeal CommunityPeace, unity and diversity are perhaps few of the most essential characteristics of an ideal community. Such a community would foster solidarity yet heartily welcome newcomers. Its members would be of diverse backgrounds and would be able to freely practice their various cultures and traditions. They would embrace their personal ideologies while being tolerant of those of others. The community would be rather dynamic, with constantly changing people members and traditions while maintaining a stable total population. Lush green grasses, beautifully landscaped houses, and long winding driveways would characterize the largely suburban community. Children would be able to play freely in their yards while their parents would freely converse with kind neighbors. Though shops and businesses would be nearby, houses would be on quiet, tree-lined streets. Well-maintained schools, parks and playgrounds would be plentiful and laws and regulations would be strictly enforced. Children would be heard chatting as they walk into and out of state-of-the-art schools and libraries onto clean, safe streets. Education would be encouraged, if not stressed, through these and other institutions. Mornings would be busy with children preparing for school and after-school activities while adults for work. Most people would have the typical nine to five workday, allowing time for family dinners and relaxing together. Car and house doors could safely be left unlocked while emergency response and police services would be among the best in the nation. Various parades, local concerts and fairs would be held throughout the year, and a community center would unite and provide support for community members. Lastly, this small, quiet suburban community would be open to—or at least tolerant of—change. Immigration Movie Clip-In AmericaThis segment from In America perfectly captures the dreams of many immigrants when they first arrive in New York; that is, those of hope, success and good fortune. As immigrants first enter Manhattan, they are often overwhelmed by the bright neon signs, large billboards and diverse people—a feeling that is perhaps best described by the word ‘magic’ heard repeating in the song. This featured song, “Do You Believe in Magic?” fittingly seems to capture this feeling of freedom, pleasure and perhaps even prosperity felt by the family. This song not only sets the stage for the story of a typical immigrant family, in this case, Irish, in pursuit of wealth and freedom, but also describes the truly unique aura radiated by an equally unique city. It also effectively evokes the family’s lighthearted and optimistic feelings in the viewers, compelling them to sympathize with the family. Furthermore, New York—with its distinctive lights and sites—is seen in all its magnificence. The viewer is also able to sense hesitance and worry, especially apparent through the father’s eyes. Thus, by showing the typical New York environment, featuring the song, “Do You Believe in Magic?,” and showing the emotions the family feels, this segment is able to rather successfully capture the experiences of newly arrived immigrants.

Midterm EssaysClass Notes The three competing sociological theories, assimilationism, multiculturalism and cultural pluralism present a distinct view of American society, however, to an extent, each is seen in society today or at least, has existed before. Careful analysis of these paradigms of diversity suggest that the ideology of cultural pluralism seems most applicable to the US, and especially New York today. Assimilationism refers to the idea of absorbing all ethnic groups into a larger culture—one that is distinctively American. However, it is important to note that this refers simply to an ideology as opposed to assimilation, which refers to the actual, scientific fact of groups adopting a new culture. The ideology thus supports the metaphor of the “melting pot” by advocating conformity and loosening, or perhaps even severing, ethnic ties. Assimilationists encourage efforts to achieve a national unity and culture, including effectively welcoming immigrants to American society, hoping that they respond by accepting American culture. Additionally, they criticize programs such as affirmative action, which not only embrace the existence of various cultures, but also promote diversity and retention of these values. Though assimilationism seems an admirable way to promote unity in theory, it is far from so in practice. If employed, it would promote a complete dissolution of the countless cultural practices that make America as diverse and unique as it is. With these origins in mind, it is moreover unlikely, or even impossible, to force complete conformity. The ideology of Multiculturalism, very much of an opposing view, is the idea that cultural an ethnic identities should be preserved, and are all equal in value. Multiculturalists argue that all of the subcultures that compose American society occupy an equal level in society; none should assume even a slightly superior position. They advocate that all cultures should be included and that such inclusion only improves American society. Thus, multiculturalists promote the ideas of bilingual education and affirmative action—both of which give preference to, and support the existence of, equal individual cultures. Multiculturalism is thus existent through English-Spanish bilingualism, as in street signs, countless types of forms, and even operating manuals for countless items. They believe that forcing assimilation would only lead to rebellion and unease. Additionally, multiculturalism has been broadened beyond simply ethnic groups, to include other groups such as homosexuals. Thus, though multiculturalism appropriately calls for diversity and a preservation of cultures, it seems likely to not just change, but disrupt American tradition. Cultural pluralism, a policy that seems to intermediate between the previous two, promotes the co-existence of various cultures, while having a one dominant culture composed of aspects of these subcultures. In American society, influence of this policy is seen through the existence of Churches, Synagogues and Mosques in a single community. Historically, the Harlem Renaissance reflected this principle as it promoted inclusion of African-Americans in mainstream culture. By promoting the peaceful co-existence of minority groups that maintain their cultures while simultaneously participating in a more dominant culture, the term, “cultural pluralism,” is perhaps the most fitting today. This theory almost appears as an effective compromise between the opposing theories of assimilationism and multiculturalism. Cultural pluralism promotes tolerance and diversity, while also maintaining a certain degree of national unity. In doing so, it fitting for New York City, a city composed of people countless cultures. It is evident as though many immigrants live in ethnic enclaves, they respond to, and adopt certain aspects of American culture as well. World in a City, Joseph Berger Throughout World in a City, Joseph Berger discusses how neighborhoods have changed; he often clears common misconceptions about neighborhoods and explains, or sometimes infers why this has happened. Perhaps the best examples of neighborhoods changing over time are that of Astoria and East Harlem. Astoria, Queens, was once a thoroughly Greek neighborhood however, it has now changed: no longer are the Greek cafes bustling late at night. Successful Greeks have left for nicer areas, while North African and Middle Eastern immigrants have taken their place. These immigrants, along with those from Morocco, Egypt and Tunisia now crowd into mosques, Middle Eastern stores and cafes. In fact, the number of people that speak Arabic rose 80% from 1990 to 2000. Astoria now also has a Bangladeshis, Serbians, Bosnians, Ecuadorians and even Manhattan professionals looking for cheaper housing, and a short commute. Also prominent are the Brazilians who often come well-educated, even as professionals but are forced to adopt blue-collar jobs. The population of Astoria has thus changed significantly: whereas once half the population was Greek, this population is now diminutive. It is fitting that Middle Easterners and North Africans have succeeded the Greeks because of the similarities in cultures; the new immigrants perhaps found it easy to adapt to the similar Greek ways. Berger describes that the some foods of the cultures overlap: both Middle Easterners and Greeks foods such as okra, lentils, honey-coated pastries and kebabs. Additionally, there are certain cultural similarities as well. In both, men enjoy going out, smoking and playing games such as backgammon in homely cafes. Thus, the similarities between cultures are what seem to have led to the ethic succession in Astoria. East Harlem, which extends from Third Avenue to the East River between 96th and 120th streets, has also changed significantly: whereas once it was a flourishing Italian neighborhood, it is now largely Spanish with Mexicans and Dominicans now being the most numerous. At one time, Italian stores and Roman Catholic Churches thrived but now, though a few of each remain, they have largely lost a distinctive Italian vigor. The neighborhood now has not only Puerto Ricans that settled after World War II but also a new middle-class of the more recent immigrants from the island. However, overall, the Puerto Rican population has declined as they now make up 31.6% of the population compared to in 45.3% in 1960. However, this number seems to be increasing again as Puerto Ricans are returning to regain what they once had. These exiles have seen suburban life but are returning to what is now called “Spanish Harlem,” to enjoy the bustle of this area. The percentage of Mexicans has increased though, now at around 9.4%. Much like the Greeks, Italians left East Harlem for more suburban neighborhoods, especially those in Brooklyn and Queens, but also those in Long Island. Thus, in East Harlem, Puerto Ricans, as well as Mexicans and Dominicans are drawn by bodegas, botanicas and festive neighborhood, earlier Puerto Rican immigrants established in the 1950s. The Puerto Ricans want to revive the buildings and infuse the neighborhood with the same flavor of earlier times. In both neighborhoods, it seems that the changes that are taking place result from immigrants wanting to keep ties with their native cultures. In Astoria, Middle Easterners are drawn, almost intuitively, by the similar Greek culture, while in East Harlem Puerto Ricans are drawn to what once existed of their own culture. Thus, both ethnic successions have resulted in strengthening cultural ties (in the case of East Harlem), or at least trying to maintain them (in Astoria). Beyond the Melting Pot, Nathan Glazer and Daniel Patrick Moynihan Through their analysis of the Puerto Rican migration, Glazer and Moynihan suggest that these migrants did relatively poorly in New York in fact, they seem to suggest that the Puerto Ricans would advance the least as they fail to assimilate to the degree of the others. This failure was attributed to several reasons including the ease with which they could return home, the failure to advance financially, the lack of strong cultural or religious ties, and their lack of education. Glazer and Moynihan suggest that for Puerto Rican the pressure to assimilate was relatively low due to the ease with which they could return to the homeland; these immigrants realized that returning to homeland was not a sign of failure or incompetence, in fact, movement was too easy for it to even have any real significance. In fact, they were so likely to return home that Luis Ferre, a candidate for governor of Puerto Rico campaigned in New York, as 30,000 Puerto Ricans were expected to return home each year. This also undoubtedly led to little organization among the groups in New York. Leadership roles were often assumed by non-Puerto Ricans; the first Spanish-speaking city magistrate, Emilio Nunez, was born in Spain. Additionally, a Dominican owned the most popular Puerto Rican newspaper and though the newspaper focused on news pertaining to this community, it was by no means a product of its people. This scenario applied to many aspects of the Puerto Rican community. Thus, though Puerto Rican migrants were numerous, they seem failed to establish strong community organization like the Jews or Italians, and perhaps more disappointingly, most of what they did for their community was initiated and even sustained by non-Puerto Ricans. The weakness of Catholic Church on the island directly corresponded to a lack of the influence of the religion on Puerto Ricans in the mainland. In Puerto Rico, the Church was not national and its influence was minimal in terms of shaping families size and organization and in politics. Thus, on the mainland, Catholicism served the basic functions of baptizing, marrying and burying; it did little more than serve as a general frame of life (pg 103). In a strange reversal of roles, the Catholic Church in New York made an effort to recruit Spanish-speaking priests and Puerto Rican members, as opposed to the conscious efforts of other European Catholics in establishing parishes and religious schools. In fact, only 15,000 Puerto Rican children attended Catholic schools as opposed to ten times as many that attended public schools and among 41 Spanish-speaking parishes in 1961, there was only one Puerto Rican priest. Thus, the minimal role of the Catholic Church seemed to almost hinder Puerto Ricans from assimilating, into American society. This lack cultural development significantly contributed to the lack of development of the community in New York and more so, severely limited the assimilation process. Glazer and Moynihan also argue that the Puerto Rican’s lack of socioeconomic success contributed to preventing them from joining American society. They present statistics such as the Puerto Rican median income was $3,811 as opposed to $4,437 in New York as a whole, and 9.9% of Puerto Rican males were unemployed in 1960, the highest of all racial groups, showing the considerably lower standard of living among Puerto Ricans. This low standard of living motivated many to return home, bringing this group further from assimilation, or “melting into the pot.” Thus, it seems the metaphor “the melting pot” does not accurately reflect the experiences of Puerto Rican immigrants, or at least those of mid-twentieth century discussed in Beyond the Melting Pot. These migrants failed to follow the typical assimilation patterns of other immigrant groups, namely the Jews and Italians. They didn’t have strong, unifying culture at home, hindering the development of one abroad. They also joined the lowest rungs of American society, again giving them little opportunity to adapt American traditions. Finally, many returned home because of these failures, removing the pressures of assimilating all together. From Ellis Island To JFK, Nancy Foner Through careful analysis of the immigrants of the first and last decade of the twentieth century, Foner rather vividly portrays the reasons they came, their experiences here and even their future in From Ellis Island to JFK. In doing so, she effectively disproves a series of myths too often thought about older immigrants. These include not only differences between the two groups, but also similarities that are very rarely recognized. One fairly evident difference between the old and new immigrants involves settlement patterns: while immigrants of the early 1900s often concentrated in ethnic enclaves, more recent immigrants tend live in neighborhoods throughout the five boroughs. Early immigrants tended to confine themselves to areas around where they worked, specifically the lower east side of Manhattan, in cheap accommodations. Even the term “overcrowded” even seems an understatement as in 1910, a record 2,331,542 people resided in Manhattan, a number 850,000 people smaller than the population today. More remarkable is that a sixth of this population was concentrated below 14th St, a section one eighty second of the entire region. In terms of selecting neighborhoods, there were few alternatives for the early Jews and Russians as living to far from their source of jobs was too much of a luxury; they needed to quickly take advantage of any job openings and commuting was made impractical by the long hours and low wages. Immigrants were thus forced to live in the slum housing, most often tenements that allowed access to the city’s industrial areas that would provide work. While the lower east side became a “Jewish cosmopolis” (pg 40), just a little to the left became the site of Italian colonies. Though more recent immigrants still cluster in ethnic enclaves such as Chinatown, many recent immigrants are able to reside in what were once middle class settlements, some even purchasing their own homes as they were able to find better jobs. The perfect example of this seems to be Jackson Heights, a once luxurious, ideal suburb in the 1920s, home to middle class whites, which became increasingly inhabited by Hispanic and Asian immigrants, of a lower social class. Additionally, suburban regions, including Long Island and Westchester have undergone significant transformations as many more immigrants have settled here. Not only are immigrants able to afford suburban housing because they are doing better economically, but also because New York has been completely transformed; this latter fact makes it almost impractical to compare current and past living conditions. An important similarity between new and old immigrants involves the occupations of these immigrants: in both cases, a significant portion has had to work in unsafe working conditions at low-paying jobs due to their lack of adequate skills. In both cases, they are forced to work long hours for low-paying jobs, often performing tasks no one else wants. The early Jewish immigrants mostly found jobs in sweatshops in the lower east side, the fashion capital of the nation at the time. Conditions in these sweatshops were unimaginable; to name just a few, they were notoriously overcrowded, accidents were common, and workers had to pay for electricity to run their machines and were often cheated out of hours they had worked. Though modern labor laws have significantly improved working conditions, they have in no way ended such conditions. Many immigrants still arrive with little more than the clothes on their backs and are forced to join these lowest rungs of the labor market, and moreover, of society. Thus, though many immigrants arrive with much many more skills, often even professionals with higher education, others arrive just as the Jews and Europeans of the early 1900s, with few skill and resources. Neighborhood ProfileTract 772, Brooklyn

Education

Race

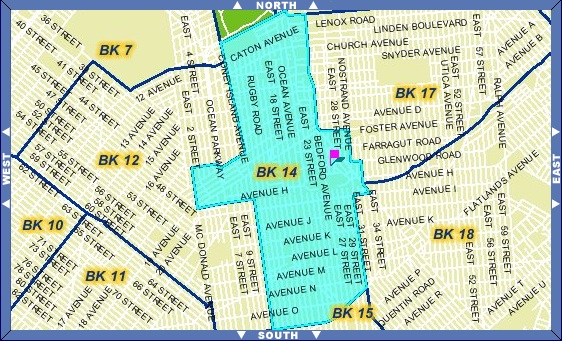

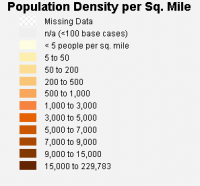

The 2000 census tract information shows that my neighborhood, of tract 772, has a much greater Black population than does Brooklyn as a whole, with 77.7% and 42.9%, respectively. It also shows that the white population, comprising 13.7%, is much smaller than the 43.2% in Brooklyn. Similarly, the Hispanic population is much less than that of Brooklyn. The Asian population of Midwood is insignificant, consisting of less than 1,000 people. Census data also shows that the majority of ancestry reported, 43.1%, was from the West Indies, with the next largest portion from Haiti, comprising 22.9%. Since Asian and European population is insignificant in this area, its fitting that ancestry from these areas is only .1% or less. The 2000 Census tract also shows that 41.9% of the population of this neighborhood is foreign born while the borough’s foreign-born population is 37.8%. The data also shows that about six percent less of the population of my neighborhood describes themselves as not being able to speak English “very well,” than that of Brooklyn. Interestingly, this applies to a little above or just below half of both populations. The percent of population in the labor force in this area is also noticeably higher (about 10%) than that of the entire borough as is the median income (about $19,000 higher). Caribbean FlatbushThough many neighborhoods, including Ditmas Park and Prospect Park South, are thought to be included in the loosely-defined Flatbush neighborhood, the region to the north of Brooklyn college, can be considered Flatbush proper [1]. This area has been home, at various times, to members of diverse backgrounds, including those of Irish, Italian, Jewish, African-American and Caribbean descent. Originally a farming community in the 1600s, the neighborhood evolved to a to a wealthy suburb and to now a bustling urban area [2]. The commercial hub of the Flatbush neighborhood has historically been thought to be “the junction”—the three-way intersection of Avenue H, Flatbush and Nostrand Avenues. Most of the area’s population includes Caribbean immigrants and the 2000 census data shows that 76.3% of the population is identified as black[3]. Among these are those of Haitain, Jamican, Trinidadian or Tobagonian descent and more recently, those of West Indian descent The Caribbean community has done much to retain its values abroad and this influence of is seen through the numerous hair salons, grocery stores, pharmacies, laundries and restaurants that serve island inspired-cuisine. Also, since many look sent money to support families on the islands, there are Western Union and Money Gram services.

Coney IslandThere to HereI was born on November 7th, 1989 in Islamabad, Pakistan, the hometown of both my parents. My dad worked as a finance director for Pakistan International Airlines at the time, so he traveled a lot, and we even had to move several times. In Islamabad, my family was fairly well established, with a home in the Defense Phase 1 area and other properties in F-10 Sector. Luckily, never we faced any social or financial troubles, and really never planned on moving. Most of my extended family lived in, or near, the area so the distinction between immediate and extended family was blurred, or perhaps even nonexistent. Thus, when my dad found out that he would have to work in Japan for two years, my parents were hesitant, in fact, completely worried. However, they knew it was necessary as it could provide new opportunities. Thus, we would have to move to a completely new place, leaving much behind, since our apartment in Tokyo, would not nearly be as commodious. Moreover, the cost of moving these things would most likely exceed their value.

Islamabad, Pakistan Wikipedia

Tokyo, Japan Kevinwell's Found

|