Music and Community Development

From Seminar 2: The Peopling of New York City

Contents |

Caribbean Music

"History is built around achievement and creation, and nothing was created in the West Indies." - V.S. Naipaul, a Trinidadian Nobel Laureate. With just a glance at Caribbean culture, it is clear that V.S. Naipaul could not have been more mistaken (Manuel 1).

Filled with vitality and creativity, music has become an integral part of cultural identity in Caribbean communities all over the world. It has developed into one of the most significant and dynamic aspects of cultural expression in a region that has constantly encountered political and ethnic discord (Reference source). Over the course of history numerous musical genres, shaped by many different sociohistorical factors, have sprang into existence. Colonialism, slavery, and social stratification gave rise to a unique composition of African and European musical elements. Advancements in telecommunications and interactions between migrant communities have not only strengthened transnational networks, but also facilitated the fusion of many other distinct musical styles. From Cuban Rumba to Trinidadian steelpan, music has transcended ethnic and cultural boundaries, and has come to reflect today’s increasingly multi-ethnic societies (Manuel 1-2).

Music has also played an active role in the sociopolitical development of the Caribbean, and immigrant communities abroad. In some cases it is a means of communication and unification at home, while in other countries diverse genres have sparked a Pan-Caribbean consciousness. This is particularly evident in the United States where it is difficult to transcend the racial boundaries that have undoubtedly descended upon the West Indian community (Manuel 1-2).

Colonial Influences

Indigenous Indian Caribbean music was very simplistic in form and said to have been influenced by different Mesoamerican groups. Focused on mythology, participants would encircle musicians and chant to the rhythm of rattles, scrapers, and drums. Most of their musical heritage had been lost or diluted by the arrival of the Spaniards. In order to work the land they had seized, the Europeans imported African slaves in large numbers (Manuel 2-5).

Throughout the Caribbean, African elements from different regions were incorporated into musical traditions. Acculturation with European music was also common, as unique blends began to emerge. Nevertheless, recognizable African properties remained prevalent in Caribbean music, particularly the concept of collective participation. Everyone, they thought, is born with a certain degree of musical flair that is cultivated through communal involvement, usually in communities with fewer ethnic and class divisions. African-derived music placed great emphasis on rhythm to control the attention of the audience and enable a rich and captivating beat. Syncopation and polyrhythm were two complex African methods used to accompany common call and response vocals. Usually the songs would contain constant repetition and variety leaving an open pattern formation, called a cellular structure. This variation stood in stark contrast with symmetrically structured European-derived music (Manuel 5-17).

The Spaniards, British, and French diluted the African elements even more, bringing classical, folk, and popular music to the region. Although the Europeans shared many similar traditions, such as carnival gatherings and oral transmission, they brought new instruments (the Spanish guitar) and harmonies. Social dances, such as the waltz and mazurka, blended with syncopations and other African features. Creolization, the combination of African and European heritages, such as the Cuban rumba –African rhythm with Spanish language –was a significant aspect of evolution for the Afro-Caribbean culture in the region (Manuel 5-17).

Different areas had varying degrees of African and European musical presence, causing a distinctive sound in some cases. Iberian and French colonialists were much more accepting of African cultural independence than British and Dutch colonies. Roman Catholicism, rather than Protestantism, also blended easier with the African worship rituals. The amount of time the slave trade lasted in a particular region also influenced how developed and strong the neo-African culture became, and in turn its effect on music. Britain for instance stopped importing slaves by 1804, therefore cutting off ties with new practices back home. Lastly, if a colony was a plantation region with a greater population of slaves, as opposed to a European settler colony, African elements were often more prevalent in the musical genres that emerged (Manuel 5-17).

Music and Community Development

One may think identity formation and celebration the primary functions of music in the West Indies. However, it is in fact very important in the sociopolitical development of the region and in its immigrant communities abroad.

The Caribbean

Music in the West Indies plays a significant role in the political arena. Not only is it a way to celebrate or forget the political and economic woes, but also a way to express concerns and opinions. "Through music, men and women can voice aspirations and ideals, strengthen group solidarity, and transcend adversity by confronting it and transmuting it into song. (Manuel 243)" Many genres, such as Puerto Rican danzas, blatantly opposed imperialist powers. Several musicians also used music to voice political and social criticisms. In the twentieth century, when American influence had peaked in the Caribbean, despite foreign leverage in the music industry many continued to use the power of music to confront political restructuring and injustices. This was especially evident in the 1960's and 1970's with decolonization, reflected in the optimistic themes of independence that emanated from the region's music (Manuel 243-246). In Jamaica, reggae was a focal point of religious expression (Religion) and addressed political unrest that prevailed during rivaling political parties. Politicians in Trinidad used music as a mode of communication on the island and to spread the news (Manuel 2). In Bob Marley's quest for political peace in the latter part of the 20th century, he sang:

"One Love! One Heart!

Let's get together and feel all right" (One Love/People Get Ready).

Aside from its contributions to the political realm in the West Indies, music also addressed other social issues related to community development including racial divisions, gender inequalities, poverty, and even AIDS. It was a way of communicating, instilling an idea, spreading awareness, or calling for unity. As Mighty Sparrow sang:

"The biggest bacchanal is in Trinidad Carnival.

Regardless of color, creed, or race,

jump up and shake your waist" (Manuel 205)

The 1960's in the United States was a period of social revolution, dominated by the youth, against what had been established in this country. It was also a time of Black empowerment through the Civil Rights Movement and a simultaneous influx of West Indian migrants. Youth expression spread throughout the Caribbean: "Early salsa emerged as the youthful voice of the barrio, militant and optimistic, chronicling the vicissitudes of lower class urban life with a dynamic exuberance. In Jamaica, the sociopolitical ferment of urban youth found expression in roots reggae...Calypsoes by Black Stalin, Chalkdust, and others also reflected the influence of the Black Power movement and the broader political consciousness of the period" (Manuel 245).

Transnational Tunes

As migrants settle abroad, many retain close connections with family and friends in the home country. It is very difficult, for the first generation especially, to let go of West Indian traditions. Assimilation poses many obstacles, particularly in regions where racial boundaries are imposed upon them. Maintaining traditions from home enables them to construct a distinct ethnic identity, evident in the Labor Day Carnival (Carnival). However, equally as important, is the role that West Indian music and traditions play for the second generation and in the development of the community as a whole.

Brooklyn's Caribbean Currents and Community Development

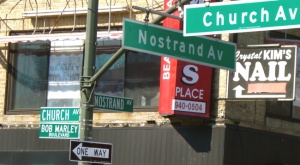

Caribbean people have been on the move for centuries, voluntarily or involuntarily, carrying their culture all over the world. Different social, religious, and economic contexts gave rise to a plethora of complex and multi-layered musical genres. In the Americas, surviving musical traditions have become definitive methods by which immigrants reconcile ethnic and cultural identities in mixed societies. As New York’s Brooklyn became a hub of West Indian immigration after the first half of the 1960’s, various musical genres (African soul, Bajan spooge, Jamaican ska, dance hall, and reggae, Trinidadian soca, calypso, and steelpan, and Haitian merengue and konpa) and festivities were transplanted. (Expressive Culture)

Music in West Indian communities is a method by which to formulate an identity on foreign soil. It is precisely this identity however that brings the community together and allows for the establishment of an intraconnected niche. It is this group solidarity that creates a strong sense of civil responsibility in the community, evident in the different organizations dedicated to its development (churches or family services).

Although multinational record companies greatly influenced the subject matter of incoming music, many artists held onto their roots. This lead to a unique blend of popular music, rap and hip-hop blended with African-derived beats and even Spanish rap mixed with reggae. Many West Indians have felt categorized as racially black in American society. As music continues to intermingle it presents an even more challenging cultural mix. Unlike their parents, many second-generation West Indians have found traditional music of their nationality less compelling. This continuous blend of cultures will make it increasingly difficult to differentiate between the two groups, which may ultimately affect the community's dynamics.

In Brooklyn the Carnival was established to represent West Indian culture. Migrant musicians, however, found more than a celebration, but temporary work during the festivity. What began as an orderly procession of steelbands, evolved into a massive display of turn tables and deejays situated on floats. The Carnival became a symbol of New York's diversity, bringing thousands of spectators to the area. Additionally, it attracted political attention from politicians looking for votes by appealing to the diversity of the community. The Carnival has also lead to the development of several organizations dedicated to the preservation of traditional music, such as the J'Ouvert City International (Allen 263) and the Caribbean American Sports and Youth Movement. Both organizations are dedicated to aiding in the development of West Indian children in Brooklyn by creating steelbands (Lornell and Rasmussen 117).

Works Cited

Allen, Ray. 1999. "J’ouvert in Brooklyn Carnival: Revitalizing steel pan and Ole mas traditions". Western Folklore, 58: 14

Caribbean Festival Arts. Washington, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1988.

Manuel, Peter. Caribbean Currents. Philadelphia: Temple UP, 1995.

Musics of Multicultural America. New York: Schirmer Books, 1997.

South America, Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean. The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. New York and London: Garland Inc., 1998.