Central Park

From Science and Technology: Baruch IDC 3002H

Contents |

Introduction To Central Park

| Location |

Manhattan |

|---|---|

| Type |

Urban Park |

| Location |

Manhattan |

| Size |

843 Acres |

| Year Opened |

1859 |

| Annual visitors |

25 million |

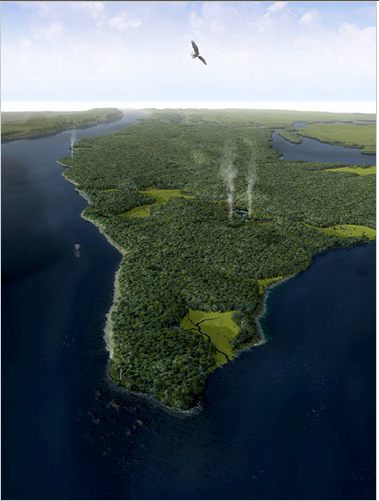

Manhattan wasn’t always the robust city it is today. At one time it was a pristine forest filled with hundreds of diverse animal and plant species, many having ceased to exist in the area. Central Park is the heart of Manhattan and is one of the few places where humans interact with the natural environment. If it wasn’t for the strong advocacy of a public park in the 1850s, the patch of green between 59th street and 103rd street wouldn’t exist. The long and arduous task of building the park took thousands of workers and spanned many decades. The changes have not stopped even to this day. The creation of Central Park is not only historically important but ecologically as well. Because of the forward thinking of that generation, we are now able to study the effects that urbanization has on the environment, something that must be looked at as places all over the world continue to urbanize. This wiki shows the history and ecology of Central Park as well as a detailed explanation of a small mammal trapping we conducted in the North Woods. We chose to focus on these aspects because the park's creation had an unequivocal impact on the park's ecology. The trapping let us know just how much the mammalian species of the park had changed since its inception.

History of Central Park

Early History (1600-1850)

F. Scott Fitzgerald. The Great Gatsby.

This was the setting of Central Park. Marshes, streams, valleys, hills, and even cliffs enveloped the unhampered glorious nature of the Manhattan Island.

Eventually the year 1609 came, and the narrow green island of “Manhatta” was eternally disturbed and coerced to evolve and industrialize with the progress of mankind. The settlers progressed to create a town surrounding their Dutch fort on the very southern tip of Manhattan; New Amsterdam was born and with it Windmills were constructed and the era of colonization shrouded the ecological serenity that hovered before.

The population was expanding exponentially and unfortunately the standard of life and health was doing the opposite. Disease and poverty sped through the different neighborhoods of Manhattan with unconceivable rates, and realization of a need for change arose (Heath M. Schenker, 1987).

Bowling Green Park, established in 1733, was New York's first official park. The areas that became Battery Park and City Hall Park were also defined and protected from development in the early 1700's. Staten Island's oldest park, Veterans Park, was laid out in 1836. On April 3, 1807 the Common Council of New York appointed three commissioners, Simeon De Witt, Governor Morris, and John Rutherford, to organize the city in the "most conducive to the public good." Thus, the three appointed men created a rectangular grid of avenues and streets, which became the most familiar topographic characteristic of the city above Canal Street. Unfortunately the plan did not create enough open space for New Yorkers and was ultimately altered in the mid 1800’s to make it adequate for such a densely populated city (R Rosenzweig, E Blackmar, 1992). Decisive measures were needed to cope with living needs of New York City, and finally 840 acres were reserved in the very centre of the grid to construct Central Park.

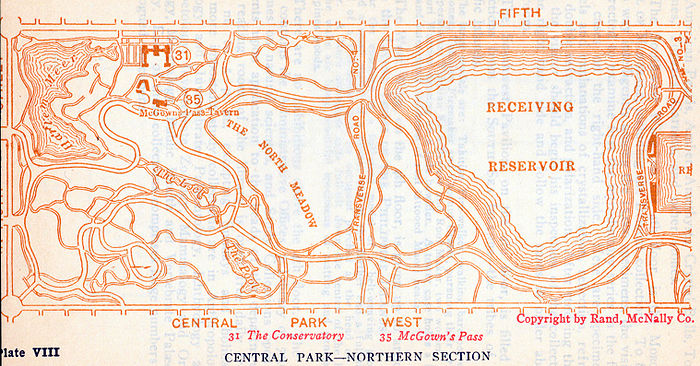

As one travels north of this area in the park they quickly come across a Ravine. This area also known as the Northwoods is a true deciduous forest of oak, hickory, maple, and ash. The forest floor is covered with leaf litter, deadwood, and herbaceous plants, such as white wood aster, Allegheny spurge, and woodland goldenrod. Further northeast is the meadow which also has a large amount of ierse plants; cone flower, cup plant, and bee balm mixed in with a variety of goldenrods, asters, and native grasses (The Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society, 2007).

Seneca Villlage (1825-1857)

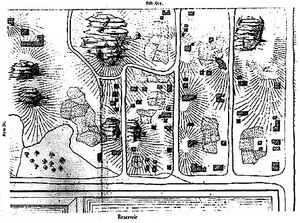

With the acquisition and zoning of this massive city space, approximately 1,600 people were displaced. Irish Farmers herded sheep, and food for the freshly settled immigrants was gardened. Moreover there was an important African American Village – Seneca Village Seneca Village existed from 1825 through 1857. It was located between modern day 82nd and 89th Streets and Seventh and Eighth Avenues. Not much is known of Seneca Village’s exact past and even the reason for its title. However the first real-estate events took place when in 1825, John and Elizabeth Whitehead sold the first piece of land in the Seneca Village area to a young African-American named Andrew Williams for $125. The Whiteheads then continued to sell other plots of land to members of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church (R Rosenzweig, E Blackmar, 1992).

This community flourished in an unusual way. It was a multi-cultural population that lived together seamlessly. Furthermore Seneca Village boasted what were Manhattan’s first African-American property owners. Although this was a small community of only 264 individuals; they were able to establish three churches, several cemeteries as well as a school. Such a peaceful town was ale to exist because of its relative isolation from the main city center of downtown Manhattan.

The Park's Creation (1850-1960)

During the 1830s and 1840s a group wealthy merchants and landowners who had gone across the Atlantic, came back envious of the public parks of European cities and urged for the need for New York to establish a comparable facility in its surrounding area. These advocates argued that not only would a public park raise New York City’s reputation but it would also offer working-class New Yorkers with open space to dwell in.

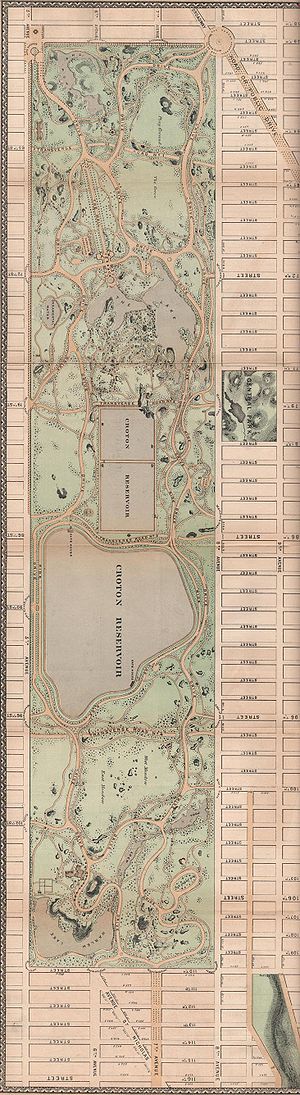

After much debate the idea for the nation’s first major public park was set on July 21, 1853 by the New State Legislature. The bill was approved and it designated a piece of land, a 700-acre area, from 59th street to 106th street, the middle of Manhattan, for a great public park.

A contest was held during 1857 for the best landscape design for Central Park. The winning design was the “Greensward Plan, “ which was designed by the writer Frederick Law Olmstead and the architect Calvert Vaux. Later on, Olmstead talked about what influenced his winning design and he had mentioned that his trip to several parks in Europe and other natural landscape in the United stated shaped his landscape design (Hallet, 2003).

The Greensward plan had many creative innovations. It called for separate circulations systems, one path for carriage drivers, another for pedestrian walks and another for equestrian paths. The commercial traffic from one end of the park to the other was concealed in the Transverse roadways, that Olmstead and Vaux created, eight feet below the park’s surface. The Transverse roadways were further concealed by the shrub belts planted alongside the road. Moreover, Vaux, designed more than 40 bridges to eliminate the difficult crossing between the different types of terrain. Later on, the bridges would themselves add grace to the aesthetics of the park. In all the design and creation of the park was more of an art project. It was created to emulate that of pastoral landscape of the English romantic tradition. However, as all funded and State commission projects there were many barriers for Vaux and Olmstead to fight and overcome over the years.

Although there was a design chosen for the construction of the park, there were still quite a few hurdles left to cross. The 700 acre area still had some 1600 inhabitants, most of whom were either immigrants of German or Irish origin or were free African-Americans. It was at this time that Seneca Village and other parts of the communities were torn down and their inhabitants evicted in order for the construction of the park to start.

The construction finally began in 1857 and it was a massive project, employing more than 20,000 workers in the decade that followed. Engineers, laborers and stonecutters cut through the Manhattan schist and granite with their tools, shovels and gunpowder and totally reshaped the area of land from 59th street to 106th street. Much of the plant species, roughly 270,000 trees and shrubs, and about 3 million cubic yards soil had to be brought over by horse carriages because the original soil wasn’t fertile enough to sustain the plant life (Rosenweig and Blackmar, 1992).

The park first opened for public use during the winter of 1859 and by 1865 Central park was getting more than seven million visitors annually. The park provided summer concerts on Saturday afternoons and schoolboys were allowed to play ball on the meadows with a note from their principal, however they were many strict rules governing park use. These rules were repeatedly contested and the park’s commissioners gradually gave became more lenient in how the park could be used. Towards the end of the 19th century, concerts were permitted on Sunday afternoons, certain attractions were permitted that before weren’t allowed. With more funding, Olmsted and Vaux were able to develop new plans for a Conservatory near Fifth Avenue and 72nd Street and a zoo on Manhattan Square, which quickly became the park’s most visited feature. Vaux and Olmstead also designed the building of both the Musuem of Natural history on the east side and the Metropolitan Museum of Art on the west side (Rosenweig and Blackmar, 1992).

During the turn of the twentieth century, because of the lackluster rules on their immigration policy, New York received over 1 million immigrants. The immigrant neighborhoods surrounded the parks borders and thus annual attendance of the park substantially increased. The majority of the park’s attendees switched from the few wealthy New Yorkers to now, which was the majority, the working class (Taylor, 1999). The latter group along with progressive reformers advocated for the establishment of facilities for active recreation. Even with all this reform after about the 1870s the conditions of the park was deteriorating. The Central Park commission was disintegrated and the maintainence effort of the park declined. Trees, shrubs, and worn out lawns were left to be and weren’t replaced.

Another hurdle that had to be overcome was the introduction of the automobile in New York City and with it came the burden of pollution. Many of the parks planners fought to ban the automobile in Central Park, however, as the automobile became more common place in New York City their arguments had little backing and by 1932 traffic lights were installed in the park itself. When Fiorello LaGuardia took his post as Mayor of New York City he placed Robert Moses in charge of a new centralized citywide park system. In his first year, Moses replanted trees, shrubs, and in time introduced many of the facilities advocated by the progressive reformers. During this time a “New York Times Magazine declared that "Central Park also has a new deal." It pointed to "the brand-new brick-and-concrete zoo" that replaced the "hideous old wooden sheds," the "swank restaurant and cafe [Tavern on the Green] now housed in the shined-up sheepfold buildings," "the garden plaza enclosed by the new zoo," "the refurbished State Arsenal," the extensive "plowing, seeding, planting, and replanting," and the new athletic fields on the North Meadow that gave the "grass effect of a big-college football field or the polo field of a country club" (Rosenweig and Blackmar, 1992).

Robert Moses was able to accomplish so much was because of the assistance of federal money during the Depression through the new deal program. Laguardia had a good relationship with President Roosevelt at the time, the funds from the New Deal were allocated for the beautification of the parks. Over his tenure as the shaper of the city, Moses built over 20 playgrounds on borders of the park, renovated the Zoo by building cement and brick building, realigned the Transverse roads to accommodate automobiles, and added recreational facilities to the North Meadow.

Contemporary Central Park (1960-Present)

The coming of 1960 in a sense came as the start of a twenty year decline in Central Park’s history. This was largely due to Robert Moses’s departure as Parks’ Commissioner in 1960. During the twenty-six years Robert Moses spent as Commissioner, parks all over New York City were maintained in great shape. However, after 1960 Central Park slowly started to deteriorate. Vandalism was especially prevalent at night in the alleys of Central Park. New York City residents called the park a “Danger Zone” after nightfall. Lowered maintenance, less funding, and a reduced amount of Park personnel resulted in infrastructure being covered in graffiti, less garbage pickup, more littering and a rise in illegal activity on the park grounds (Kinkead, 1990).

The poor state of Central Park in the 1960s can be largely attributed to the overall state of New York City at the time. New York City was going through an economic recession and the crime wave was rising. Many inhabitants of the city took the route of “escaping” the problem and moving to the suburbs all together. The NYC Parks Department, already suffering from the afore-mentioned impediments, wanted rise the popularity of the park and to make the park even somewhat attractive to the public. This resulted in a much more “lenient” standard of activities performed at the park. Central Park became a spot used for New Year’s Eve Celebrations, summer concerts, protest rallies and peace marches. Some of these activities became important highlights in the city’s history but because of managerial oversights and poor maintenance these events often hurt the park ‘s landscape even more in terms of litter build up and plant destruction.

Despite the gloom and doom of the early 1960s, not everything was bad for Central Park. The 60s saw the start of annual performances in the park such as 1962’s “Shakespeare In The Park” which has been going strong until this day. Central Park’s value was realized in 1964 when it became a National Historic Landmark. In 1975 several groups joined forces and came up with ideas on how to revive the park resulting in the Central Park Conservancy in 1980. The City and the Conservancy worked together, through issuing of bonds and private funding, in the form of projects that would restore the park.

The Conservancy started out slow in the early 1980s mostly charging its man power from interns and a small staff. Through the “Broken Windows” theory, the Conservancy started with little things such as cleaning up litter, fixing broken benches and light posts and cleaning up graffiti. According to Conservancy president Douglas Blonsky, “Graffiti doesn’t last 24 hours in the park” (Blonsky, 2007). The idea behind this was that the general public would notice small changes first and not further progress the destruction of the park. Instead of painting new graffiti and seeing it gone a day later, graffiti vandals would eventually stop because of the futility of painting it every day.

The mid-1980s saw the introduction of the zoning system in Central Park in which the park was divided into territories all with a different supervisor. The 80s and the early 90s saw the completion of many projects in the park including Strawberry Fields, Shakespeare Garden and the cascades. New Yorkers, foundations, corporations raised a total of $77.2 million for the park in a three-year span starting in 1993. In 1995 the zone system was expanded even further when the park was divided into 49 zones, each complete with its own gardener responsible for the maintenance of the zone (Miller, 2003).

Since the early 1960s until 2007, the Conservancy had invested approximately $450 million in the restoration and management of the Park. The Conservancy contributes over 85% of the annual operating budget of over 25 million. Over the recent years, the park has largely depended on the work of its volunteers. In 2004 for example, the volunteers contributed with 32,000 hours of work in the park.

Just as in the past, Central Park is now back to being a top park in its class. The Conservancy’s efforts to build a world-class park have really worked and it has established a new standard in park care. Through continued funding, maintenance and the collaboration between New York City and the Conservancy, the future is bright for Central Park.

Ecology

The ecology of Central Park has steadily changed since the park’s inception. Once a rich environment teeming with natural wildlife, Central Park has been transformed into nothing more than a relaxing getaway for overly stressed city dwellers. However, the park is still home to many species and some even thrive in the hodgepodge of trees, fields and roads.

Extrapolating from an 18th century British Headquarters map, it was hypothesized that Manhattan boasted an impressive 21 ponds, 108 km of streams and 54 separate communities. Central Park alone housed the longest hydrological network in Manhattan, known as Old Arch Brook (Sanderson and Brown, 2007). This extremely moist environment would later be drained when city planners decided to install the park. Now only a few bodies of water remain in the space, several of them having been artificially installed.

During the park’s construction, 2.5 million cubic yards of stone and earth we either added or taken away from the land. 300,000 cubic yards of gneiss rock was leveled and used for pavement. Once the foundation was laid, the entire area was covered with two feet of topsoil (Rosenweig and Blackmar, 1992).

Along with the new soil, we can assume that non-native microbes, insects, and worms would have been brought over as well. The inadvertent introduction of non-native species, the extinction of certain terrestrial species in that area due to fragmentation, and the disappearance of their native ecological environment was all taking place simultaneously. We see that even during the years the park was in its ‘building’ phase the ecology was changing.

Currently, not much can grow on the soil of Central Park because of the perpetual walking that we do in the park. With that much impact, the soil gets compacted and it hinders the ability for plant species to grow. Central Park provides shelter for the plant species and allows for nitrogen cycling process to occur. However, there has been an increasing number of non-native worm species in the soil. Studies have shown that urban areas, much like Central Park, support higher non-native populations of earthworms relative to rural areas (Pouyat, Steinberg, Parmelee and Groffman 1997). With high earthworm richness, the study suggested that the earthworms were enhancing the nitrogen cycling process helping offset the effects of pollution. However, worms only process certain nitrogen gases. Certain areas in Central Park, such as the Hallett Nature Sanctuary have been closed, allowing for the free growth of plants.

Plants of Central Park

| Central Park Plants in 1609 |

Manhattan

Virginia Threeseed Mercury |

|---|

The plant ecology of Central Park prior to its creation consisted mainly of the chestnut-oak trees, oak-tulip tree forest types, red maple hardwood swamps, shrub swamps and in some areas hemlock-northern hardwood forest. The reason for this mix of various tree types was due to the differences in the terrain such as soil depth and moisture. Deeper and moister soils suggested a habitat that would have supported the oak tulip forest and hardwood and shrub swamps (Kershner 1998, Luttenberg et al., 1993). The ecology of Central Park presumably consisted of a combination of marine and terrestrial species due to the swampy terrain. The ecology was also able to sustain and support a rich mesophytic forest (Reschke 1990).

Hundreds of naturally occurring plant species grow in Central Park. 57% of these are native and 43% are non-native. Around 200 fewer species were found in the park in the 19th and 20th century. However, this could be because the search at the time wasn’t as extensive as the today’s research. Of the species found earlier, 74% were native and 64% were herbaceous. These plants were ones that competed well in moist environments rather than dry ones and would probably be pressed to survive in the present, drier version of the park (DeCandido et al., 2007).

Invasive species are a prevalent issue in Central Park. Over ¾ of the most invasive plant species in Southeastern New York State were found in the park. Several of these species present quite a dangerous situation for native species. For example, Japanese Knotweed (Polygonum Cuspidatum) is an herbaceous plant from Asia. It can grow in many places due to its tolerance of varying soil types and temperatures. It regenerates quickly and the size of the plant makes it difficult to control. It out competes native species in the park and forces them to relocate or cease to exist. In fact, the Global Invasive Species Database has listed it as one of the world’s 100 worst invasive species.

Park management continues to battle invasive species, including recently quelling an uprising Polygonum perfoliatum, known as mile-a-minute weed. Yet, the containment of these weedy species is time-consuming and costly. Restoration efforts are constantly taking place. Native tree species such as Liriodendron tulipifera, Quercus alba, and Q. velutina are being planted in the forested areas of the park (DeCandido et al., 2007).

Habitat loss and invasive species have contributed immensely to the diminishing diversity of Central Park. Around 178 native plant species no longer grow in Central Park and this number is likely higher. Most of the native herbaceous plants were removed during the park’s creation and were never replanted (Rosenweig and Blackmar, 1992). Plants occurring today are those that thrive in drier conditions, woodland edges, and rocky areas that make up most of the modern day park (DeCandido et al., 2007).

Animals of Central Park

Prior to the creation of Central Park, and even before settlers had arrived in NYC. The island of Manhattan was a pristine forest with many rich animal species, the majority of which do not occur anymore. As the land space was going through its metamorphic change, it had negative effects on the animal population around it. Ponds and lakes were drained. Trees and shrubs were introduced into areas in which they didn’t exist before and old trees were dug up. Over time, the animal population in and around that area changed significantly, mostly due to habitat loss, fragmentation, and human interactions.

Around 200 species of birds use Central Park as a pit stop along their migratory route from Canada to the much warmer temperatures of Latin America. Central Park is a key location for these birds as they can stop at the park to rest and feed on the flora that the park has to offer.

| Central Park Mammals in 1609 |

Meadow Vole |

|---|

| Central Park Birds in 1609 |

Sharp-shinned Hawk |

|---|

| Central Park Reptiles in 1609 |

Snapping Turtle |

|---|

Small Mammal Trapping In Central Park

Our group conducted a small mammal survey in the North Woods of Central Park. We chose the North Woods because it has been left relatively untouched by park development. It is still pretty densely forested and if we were going to find anything, it would be there. Going into the trapping, we did not know what we would catch, if anything at all.

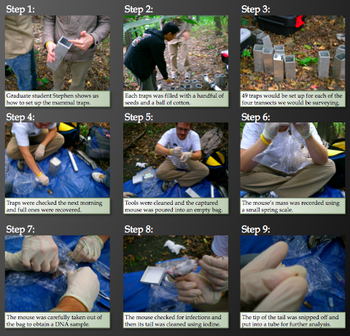

To catch the mammals we used Sherman Traps, small rectangular metal boxes that closed when pressure was put onto the trigger mechanism inside. Each trap was filled with some bird seeds to attract the mammals and a ball of cotton to keep the mammal warm inside the trap. Once the traps were filled, they were placed in a 7 x 7 grid pattern 15 steps apart from each other. We placed the traps next to small shrubs or where there was a decent amount of foliage. Flags were placed in the vicinity of the traps to make it easy to find them the following day. Four of these transects were set up in different locations. They were then left over night and checked the next day over a 3 night span.

Each mammal was weighed using a small spring scale and checked for parasites. Its age was estimated based on its weight and its sex was recorded. Lastly, a small DNA sample was taken for further analysis. To do this, the very tip of the mammal’s tail was cut off after both the tools and the tail was sterilized with iodine. The sample was then placed in a sterile tube and the mammal was returned to the spot of capture and released.

The results were pleasantly surprising. A total of 10 White-footed mice were captured, as well as 2 Norwegian rats. 6 of the 10 mice were captured in transect 1, 1 was captured in transect 2 and 3 were captured in transect 3. 1 mouse was recaptured in transect 1. There were 3 males and 7 females captured. 2 of the mice were juveniles (15g) and 8 were adults (>15g). 6 mice were infected with botflies (larval botflies use mice as hosts).

We went into the trapping not knowing what we would find or if anything from the old ecosystem would still be there. Finding the mice was a pleasant surprise as it proves that some of the original wildlife still exists naturally in such a disturbed habitat. Finding the rats was a little troubling since it could mean that they are beginning to invade the area which could cause problems for the White-footed Mouse. However, as urbanization is expanding across the globe, it is important to know how species that exist naturally will be affected. The fact that White-footed mice still survive in such a drastically altered area proves the species resilience and possibly those like it. It also tells us that nothing much bigger than a mouse can still exist in a place such as Central Park. It has become far to fragmented and human disturbance is continual.

Citations

- Blonsky, Douglas. "Saving the Park: a key to NYC's revival". The New York Post, 3 November 2007

- DeCandido, Calvanese, Alvarez. “The Naturally Occurring Historical and Extant Flora of Central Park, New York City, New York.” The Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society. 2007 Volume 69-93. 388-3415

- Hallet, Vicky. “Parks For People Olmsted turned landscape into architecture” U.S. News & World Report. Washington. Jun 30, 2003. Vol. 134, Iss. 23

- Hughes, Young, and Carreiro. “Forest leaf litter quantity and seedling occurrence along an urban-rural gradient.” Journal of Urban Ecosystems. 2003. Volume 2. 263-278

- Kinkead, Eugene. “Central Park, 1857-1995: The Birth, Decline, and Renewal of a National Treasure.” New York: Norton, 1990

- Meyerson, A. “Before Central Park: The Life and Death of Seneca Village” 1997 Volume 37-38. 434-367

- Miller, Sara Cedar. “Central Park, An American Masterpiece: A Comprehensive History of the Nation's First Urban Park.” New York: Abrams, 2003

- Pouyat and Mcdonnel. “Heavey Metal accumulations in forest soils along an urban-rural gradient in Southeastern New York.” Journal of Water, Air, and Pollutions. Volume 57-58. 797-807

- Rebele, Franz. “Urban Ecology and Special Features of Urban Ecosystems.” Global Ecology and Biogeography letters. 1994. 173-187

- Rosenzweig and Blackmar. “The Park and the People: A History of Central Park”. Cornell University Press, Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 1994. Volume 83-84. 244-276

- Sanderson, E.W. and M. Brown. “Mannahatta: an ecological first look at the Manhattan landscape prior to Henry Hudson.” 2009. Northeastern Naturalist

- Schenker, Heath. “Central Park and the Melodramatic Imagination.” Davis University of California Press. 1987

- Steinberg, Pouyat, Parmelee, Groffman. “Soil Biology and Biochemistry.” Volume 29, Issues 3-4, March-April 1997, Pages 427-430

- Taylor, Dorceta. “Central Park as a model for social control: Urban parks, social class and leisure behavior in nineteeth-century America” Journal of Leisure Research. Arlington: Fourth Quarter 1999. Vol. 31, Iss. 4

Wiki by: Wojciech Balakier, Jasper Cunneen, Daniel Goldenberg, Boris Kalendarev