American Counterculture and the Village

From The Peopling of NYC

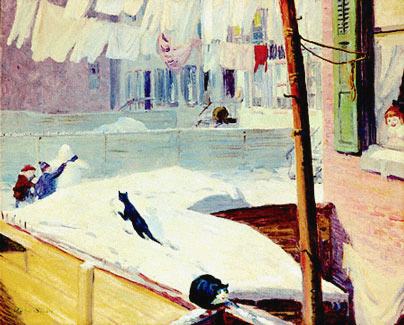

Greenwich Village, New York's Bohemia, is a rainbow blur of colors, a rush of silver creativity, still maintaining its late nineteen-sixties counter-culture personality. Tourists snapping photos with their new chrome digital cameras, students rushing, bags slung over their shoulders and large lattes and cell phones in their hands, locals looking laboriously through bright green peppers at the grocery store and ever-paparazzied celebrities shopping, all walk the same streets. What have these streets seen; what have they felt, as each year faded into New York’s horizon, another strip of fuchsia in the navy sky? Did the Beat Generation shake them with its reviving pulse? Did the riots leave them feeling raw and alive? Have they witnessed the same story being written generation after generation, a sense of pride swelling in their cemented hearts?

Contents |

[edit] New York's Bohemia

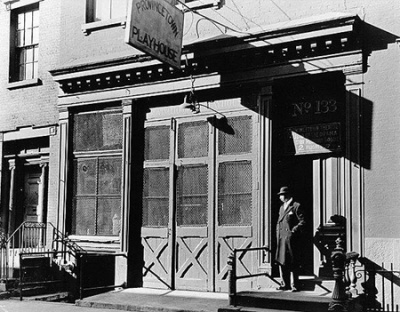

Counterculture's roots were firmly planted in the early 1900s, where avant-garde ideas in literature, art, sexual experimentation, freedom and politics blossomed. Greenwich Village was known as "an American Bohemia or Gypsy-minded Latin Quarter" (Stonehill 11), and although many of the literati and artists were relatively unknown, great literature such as James Joyce's Ulyesses was serialized by the West 8th Street Little Review (discontinued shortly afterwards because of "obscene literature"), as well as John Reed's Ten Days that Shook the World and Willa Cather's My Antonia. 133 MacDougal Street, home of the Provincetown Playhouse, was where the works of authors such as Eugene O'Neill, who was "intensely romantic and tended to idealize women" were performed (Stonehill, 32). The Provincetown Playhouse's decade of success, from 1915 to 1925, inspired the opening of many "little theaters" acrosse the country. Also on MacDougal Street were the Minetta and the San Remo, drinking places where Maxwell Bodenheim, "the great lover of the Village," who caused girls to commit suicide when he called their poetry "sentimental slush" (Stonehill, 36).

After WWI, the young writer Malcolm Cowley came to Greenwich Village with other artists, “without any intention of becoming Villagers.” They chose the area because “living was cheap,” and “friends had come already (and written letters full of enchantment),” in New York City, the most attractive city for young artists. The Village symbolized eccentricity and folly, a place for silly, strange artists with an ideological, often revolutionary, bent. It stood upon the principles found in similarly conceived neighborhoods in Germany, England, Russia, and France, whence it originated. This type of life was glorified in Henry Murger’s Scenes de la Vie de Boheme. Villagers would open their own small businesses in the area while simultaneously pursuing their artistic ambitions. If the business would succeed, it would be turned into a chain, with branches in other neighborhoods (and perhaps even other cities). If the artistic career would take off, the artist would move to wealthier, more conventional neighborhoods, and would adopt a more mainstream lifestyle.

There were eight main values of the 1920s bohemian set: individualistic development of personality, unencumbered by conventional standards and expectations; the ideal of complete self-expression in art and life; “paganism,” or worship of the body as the ultimate instrument of love; living for the moment, enjoying what one can when one still can; liberty; female equality; psychological adjustment, which is to say that one must remove repression and inhibition to be happy in any situation; and relocation to a freer society (like that of France). Cowley believes that the “revolution of morals” helped along by the Village culture was inevitable anyhow, and even if the Village hadn’t existed, this revolution would have taken place. Pleasure seeking and the underworld had always existed. The war, which took fathers to war and mothers to work, left the young largely un-chaperoned, so they could experiment and discover new things and each other. The Prohibition era sensationalized vice in a way it never had been seen before, making it attractive and exciting. The booming economy allowed for the pursuit of pleasure, and Sigmund Freud’s theories normalized what had previously been considered abnormal and evil.

That is not to say that the Village and the ideals at its foundation played little or no role. On the contrary, the counterculture of lower Manhattan shaped this new social reality, making nonconformity normal and acceptable, even standardized. This influence reached all of American society in a deeply profound way. Tourists even then flocked Greenwich Vilage in herds to the point that the Village's commerical success raised rents so high, paradoxically making it difficult for the Bohemian artists to remain there. The Village itself died, however, when the people who had made it what it was moved away, and the central institutions of the culture were weakened or closed.

The new generation of Villagers, reports Cowley, were a disappointment to their predecessors. They were not bohemians, but conformists; not idealists, but bland. The old generation bemoaned the paucity of individuality, creativity, and freshness in intellectual and artistic life, and their successors failed to do their part to correct that. Because the Village was now drained of its ideals and principles, artists and intellectuals, like Cowley himself, became disillusioned and became expatriates. The more open society of France beckoned.

Article about Arch Conspirators

[edit] The Beats in the Village

"The so-called Beat Generation was a whole bunch of people, of all different nationalities, who came to the conclusion that society sucked ." - Amiri Baraka

"Saturday I plan to go down to Greenwich Village with a friend of my who claims to be an "intellectual" and knows queer and interesting people there. I plan to get drunk Saturday evening, if I can." -Allen Ginsberg, 1943, letter to brother Eugene.

Creativity's brilliance fireworked again in the Village in the late 1940s making it "as close as it would ever come to Paris in the twenties [...] In Washington Square would be novelists and poets tossed a football near the fountain and girls just out of Ivy League colleges looked at the landscape with art history in the eyes. People on the benches held books in their hands." (Anatole Broyard, Kafka was the Rage) These writers including Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, William S. Burrough, Neil Cassidy, Gregory Corso, and Peter Orlovsky were members of the prominent Beat "Generation", although the term also refers to counter-culture radicalness. Although in a 1983 interview, Allen Ginsberg said "there never really was a Beat Generation, there was a group of friends[.]" (Laurldsen and Dalgard, 23) Ginsberg also considered himself "basically a Russian poet, put into an American scene." (Laurldsen and Dalgard, 28) Most of the literary world disdained the Beats and considered them "know nothing," though many aspiring writers journeryed to the Eighth Street Bookshop, where writers like Allen Ginsberg, lived and were respected.

Most of the Beat Generation served in World World II and the Korean War. They were mostly middle-class college students who rejected conventional social standards. They were sexually promiscious, denounced consumer ethics, were drug addicts, were prostitutes, and they were outcasts. Perhaps the Beats are defined by their non-conformist behavior and thier influence was proportionally unequal to their small number. By the mid-1955, the Beats had acheived celebrity-status though the art and literature scene began moving from Greenwich Village to the East Village. Although the Beat Movement began to decline in the late 1950s, the Beats were the predecessors of the Hippies and the Yippies.

Silent Footage of the Beats

Interview with Jack Keroac

Allen Ginsberg in Greenwich Village: His Influences and Influence

In the 1970s, the "gay power" movement burst onto the scene as the most controversial of all the civil rights crusades. However, it has been said that the original catylyst for the activity was the widespread and revolutionary effect of Dr. Alfred Kinsey's study on "Sexual Behaviour in the Human Male" (also known as "The Kinsey Report") published in 1948. This groundbreaking research helped to create an urban gay subculture and gave homosexuals a definitive sense of belonging to a community. In the years following this publication, two major gay organisations were formed--The Mattachine Society in 1950, and The Daughters of Bilitis in 1955. Both groups actively protested against discriminatory policies and were instumental as the first chapter of the gay rights movement.

In 1969, on the evening of Friday, June 27th, what is now considered to be the official beginning spark of the gay rights movement was set alight, both literally and figuratively. At The Stonewall Inn members club on Christopher Street in Greenwich Village, it was not just another night. The recent death of American cinema and gay community icon Judy Garland on the Monday of that week, and her burial on that very Friday, had prompted the holding of a wake at the Stonewall. In fact, it is alleged that "Somewhere Over the Rainbow" was playing on the jukebox when the police showed up.

At first, no one was particularly peturbed as raids by the New York City police were in fact routine, and the authorities usually just asked to see the manager's liquor license, frisked a few patrons for drugs and made general threats. However on this night, the police took it one step further and attempted to arrest some drag queens and a lesbian, forcing them kicking and screaming into the paddywagon that was parked in the front of the club.

It seems that the unjustified arrests, together with the high-strung emotions that were already in the air due to the events of the week clashed and exploded as the gathering crowd became more and more rowdy, jeering the police and making obscene gestures. The situation quickly escalated into a full-scale riot. Patrons from the Stonewall threw bottles, stones, beer cans and Molotov cocktails which set the bar ablaze. They also attacked police cars and the reinforcements. Rioting continued into the next day, June 28th, and the police ended up battling scattered crowds and clusters of angry protesters in numbers upwards of 2,000 people. Overnight, gay power grafitti slogans had been spray-painted on walls throughout Greenwich Village and Lower Manhattan.

Allen Ginsberg, a central Greenwich Village figure, was quoted in The Village Voice as saying,"You know, the guys there were so beautiful. They've lost that wounded look that fags all had ten years ago." The Stonewall Inn Riots galvanised the formation of the Gay Liberation Front in New York City in July 1969, and promoted activism against discrimination from the authorities and in the media.

The History of Stonewall with Varla Jean Merman

Our revolution didn't start with Stonewall. African-American lesbian elders tell the tales of gay New York life in Harlem, Brooklyn and the Bronx before the world-altering Stonewall rebellion. In this clip they recall, raids and suffocating laws and racial discrimination faced within the gay community.

For more information about The Stonewall Inn Riots:

"Remembering Stonewall":Interview Transcript

The Stonewall Veterans Association

The Stonewall Inn Riots on Wikipedia

[edit] Folk Revival

"I sang with Bob a couple of times impromptu, and that's also where I met him and saw him for the first time. I went to the Café Wha?. . . I didn't hang out a lot in New York City. I was very aware that that's where everything was happening."

-Joan Baez, L. A. Johnson Interview, Bloomington, IN, Aug 28, 1995

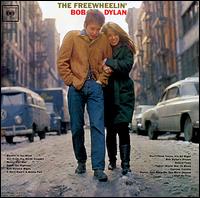

Folk music came to the Village in 1945 when a printer named George Margolin started performing near the Washington Square Park fountain. By 1960, the Park was teeming with hundreds of young aspiring musicians. In its first years, the Greenwich Village folk scene adhered to the labor theory of value. Most musicians sang and played for free in Washington Square and passed a basket for change in coffeehouses. In the late 1940s, coffeehouses had popped up all over the area, featuring folk music. The sort of “Bob Dylan slept here” nature of Greenwich Village went beyond just Bob and extended to most musicians of the genre. Nearly every folk musician/group has played the Village. The following is just a small sampling of the hundreds of singers and musicians who passed through there.

Bob Dylan

(b. 1941)

Bob Dylan arrived in Manhattan, determined to make it big, on January 24, 1961. He played Café Wha?. After that, he played all over the Village. Every hole in the wall had a coffeehouse or a nightclub, and Bob performed at most of them. A good number of his songs make references to Greenwich Village, notably, "Positively 4th Street."

Bob Dylan Performing

Joan Baez

(1941-?)

She was a folk singer who began her career in 1959 at the Newport Folk Festival.

Woody Guthrie

(1912-1967)

Dylan and most folk-revivalists began by singing his songs. He was hospitalized with Huntington's disease by the time the folk revival had begun, but Dylan, Baez, Phil Ochs, and other would visit him in the hospital and sing his songs to him. Among his songs is "This Land is Your Land."

Arlo Guthrie

Born 1947

Woody Guthrie's son, his songs include the rather lengthy "Alice's Restaurant."

Ramblin' Jack Elliot

Born 1931

He was a heavy influence on Bob Dylan.

Phil Ochs

1940-1976

Best known as a protest singer.

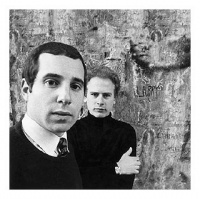

Simon and Garfunkel (Formed 1957)

Their "Bleecker Street" makes reference to Allen Ginsberg's Howl: "A poet reads his crooked rhyme/'Holy, holy' is his sacrament."

The Mamas and the Papas (Formed 1965)

John Phillips started in Greenwich Village with his first band, The Journeymen. There, he met his future bandmates, Denny Doherty and Cass Elliot. The group's early days are referenced in their song, "Creeque Alley."

Joni Mitchell (b. 1943)

Her songs include "Woodstock," which Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young famously covered.

Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach (1925-1994)

A Hasidic rabbi and master storyteller. Although much of his material was in Hebrew, he gained fame singing in the folk music clubs in Greenwich Village along with other international performers.

Theodore Bikel (1924-?)

He was a Jewish folksinger and character actor who would cofound the Newport Folk Festival (with Pete Seeger and George Wein), and would later go on to play Tevye in Fiddler on the Roof.

New Lost City Ramblers

(Formed in 1958 by Mike Seeger, John Cohen, and Tom Paley)

Unlike most folk groups of the time, who sanitized the southern folk music, The New Lost City Ramblers strove for authenticity.

The Clancy Brothers

(Formed 1955)

Group singing Irish folk music.

The Weavers

(Formed in the Village in 1947 by Ronnie Gilbert, Lee Hays, Fred Hellerman and Pete Seeger)

They were one of the first folk groups on the scene. The group disbanded in 1952 and Pete Seeger continued working solo.

Richie Havens (b. 1941)

He rose to fame in the Greenwich folk scene and would go on to open the Woodstock Music Festival in 1969.

Dave Van Ronk (1936-2002)

The "Mayor of MacDougal Street," Van Ronk was one of the founders of folk-blues. A section of Sheridan Square is named after him.

Peter, Paul, and Mary

(Formed 196) 1

The group debuted in 1961 at The Bitter End. Mary Travers worked as a waitress at Cafe Wha? when she met up with Peter Yarrow.

Places

They sang and played in clubs and coffeehouses throughout the neighborhood. Nearly every spare room or basement would house a small club or coffeehouse at some point. Some of the more established haunts of these folk artists included:

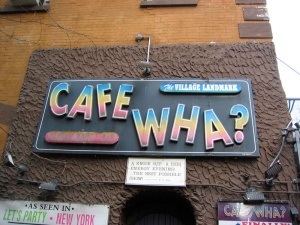

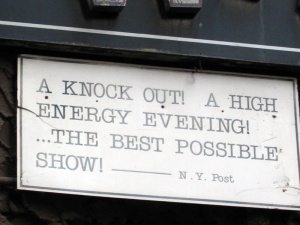

Cafe Wha?

115 MacDougal Street

Where Dylan first played. Jimi Hendrix hung out there, among many others.

The Bitter End

147 Bleecker Street

Extant 1961-2004. Everybody played there.

The Gaslight Cafe

116 MacDougal Street

Opened in 1958, as a basket house, a place where musicians would earn the proceeds of a passed-around basket.

Folklore Center

110 MacDougal Street

Opened April 1957, Dylan hung out there checking out folk recordings and writing songs on the typewriter in the back room.

Gerde's

71 West 4th Street

Opened by Mike Porco in 1952, it became a folk club in 1960. It had Monday night hootenannies and it was one of the most important venues on the Greenwich scene. It was here that the NY Times reporter Robert Shelton wrote the review of Bob Dylan that would catapult him to fame.

The Village Vangaurd

178 7th Avenue South

Opened in 1935 as a comedy and poetry club. The Weavers played here in 1949. In 1957, the club switched to an all-jazz policy.

The Village Gate

160 Bleecker Street

Opened in the late 1950s. Aretha Franklin made her first New York appearance here. Renowned Hasidic singer and storyteller Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach performed here and the live recording of his concert became his third album in 1963. Dylan wrote "A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall" in the basement.

and many others.

Roots of Bob Dylan

Simon and Garfunkel

CBGB

The Bitter End

Bob Dylan

Sources:

Hajdu, David. Positively 4th Street: The Lives and Times of Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Mimi Baez Farina, and Richard Farina. 2001.