From The Peopling of New York City

Click Here to Return to The Upper East Side

The Building of Central Park

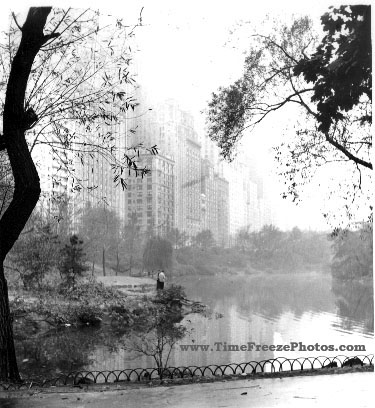

How Central Park used to be

Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux designed Central Park in 1858; the same architects that designed Prospect Park. As the city grew, more and more people started to realize the need to preserve something natural. Influenced mainly by the Romantic Movement [1] in Europe , people began voicing their desire for a park. In 1844, poet William Cullen Bryant proclaimed, "Commerce is devouring inch by inch the coast of the island and if we would rescue any part of it for health and recreation it must be done now." Writer Andrew Jackson Downing made a similar cry in his magazine, The Horticulturist, five years later. By 1850, creation of a public park in New York City became a political issue. [2]

Ambrose C. Kingsland, a supporter of the issue, won the mayoral election in 1851. Once Kingsland was in office, he asked the Common Council to take action. With the approval of the State Legislature, they bounded off 153 1/2 acres of land between Third Avenue and the East River, from 66th street to 75th streets. And in 1853, the State Legislature authorized the city to purchase the site from 59th to 106th street between Fifth and Eighth Avenues, about 624 acres of land. The beginning stages were pretty bumpy. At first the park faced harsh opposition from businessmen, but they were appeased by their new developing business opportunities. The Common Council voted to reduce the size of the park in 1855, but Mayor Fernando Wood vetoed it. But in 1857, A Board of Commissioners of Central Park was established and an Advisory Committee to help them. The head of the committee was Washington Irving. Other members included historians, writers, newspapermen, lawyers, etc. Egbert L. Viele was appointed Chief Engineer of the park. [3]

In August of 1857, they began clearing the park. A panic hit the US in 1857, delaying further progress for several years. But in 1859, the city enlarged to park to contain from 106th to 110th streets. The 843 acres park cost about five million dollars. [4]

Driving became the new fashionable trend in Central Park, and a building on Broome and Mott streets became the city's greatest carriage maker. [5]

The large numbers of carriages we see along the park stems form this trend. Some wealthy and famous people used to park their carriages close to the park. Even if it wasn't close to their actual residence, they would leave the carriages to ride in during their leisure time.

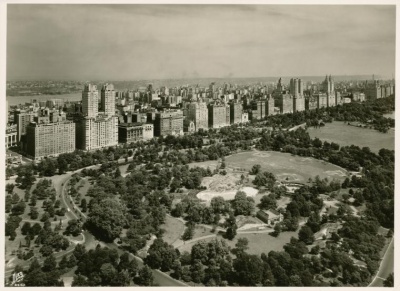

By 1873, stone, earth, and topsoil amounting to 10,000,000 one-horse cartloads were moved out of or into the park. The park is entirely man-made. By 1873, about four to five million trees, shrubs, and vines had been planted. The park immediately became popular from the moment a portion of it was opened in the fall of 1858, and its popularity increased as it expanded. By the 1860's, there were still many vacant lots south of 59th street, and the land adjacent to the park was almost completely undeveloped. Olmsted and Vaux realized how important preserving the educational value of the park was and therefore reserved a space for museums in the Arsenal place, where the Museum of Natural History stands today. The land on which the Metropolitan Museum of Art stands was already set aside for institutional use by the State Legislature in 1868, which is why the Metropolitan Museum of Art was able to be built partly inside of Central Park. [6]

People were very excited about the park and everyone imagined what they could do with so much green land. Since the park was to be used democratically, every group of people had their own ideas of what the park was to be used for. The park menaced the 1881 world's fair, which led the State Legislature to prohibit future exhibitions of the kind. Some people wanted to sell off parts of the park to boost finance of NYC, and before the turn of the century, only two places were private; the Menagerie at the Arsenal and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. They were both seen as invaders of the park. [7]

The invention of automobiles, which first become popular in the city from 1896, affected the park as people were granted permission to drive through it. They brought with them a new set of problems, namely confusion in regard to horse carriages and driveways in the park. [8]

The National Recreation Association saw the park as a place for public recreation, and shortly after 1910, Central park had a permanent tennis court and baseball diamonds. The park also contained a ball grounder, which was turned into the Heckscher Playground in 1925, its fences added as a donation. [9]

From the 1900's on, the original park was changed greatly. Playgrounds, memorials, benches, and fences were added. The original purpose of the park changed from a garden of trees, shrubs, and lawns to a more industrial, multi-functioned public space. At the same time, the natural lives of the trees and birds were falling due to neglect. [10]

In the 1930's, a $1,000,000 sprinkler irrigation system was placed underground helping bring more greenness back to the park. The Panic of 1929 prevented a lot of growth of the park and development was not resumed until Mayor La Guardia came in office in 1934. [11]

Additions such as the zoo, the Wollman Skating Rink, and many buildings, as well as the loss of the water bodies, and the removal of sheep from the Sheep Meadow greatly altered the park's landscape. Central Park was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1965 by the Department of Interior. In 1936, the Park Department started to solve the problems of crime and vandalism in the park. It empowered employees to issue summonses for violations of park regulations. The Police Athletic League was developed to educate people of the park's history and planning. It wanted people to understand that Central Park is the people's park and its main purpose is for the people directly. It also developed trained police for Central Park, similar to guards or "park maids." People felt safer in the park with the police around. Crime rate in the park did not ever exceed the rate on the street, but it was more visible in the park, which is why a special full-time team was created to maintain and organize the park. [12]

Click Here to Return to The Upper East Side

References

- ↑ a movement that saw in nature refuge from the Industrial Revolution

- ↑ Reed, Henry Hope, and Sophia Duckworth. Central Park: A History and a Guide. New York:Clarkson N. Potter, Inc. (1967): 2-14.

- ↑ Reed, Henry Hope, and Sophia Duckworth. Central Park: A History and a Guide. New York:Clarkson N. Potter, Inc. (1967): 14-17.

- ↑ Reed, Henry Hope, and Sophia Duckworth. Central Park: A History and a Guide. New York:Clarkson N. Potter, Inc. (1967): 17-18.

- ↑ Reed, Henry Hope, and Sophia Duckworth. Central Park: A History and a Guide. New York:Clarkson N. Potter, Inc. (1967): 16.

- ↑ Reed, Henry Hope, and Sophia Duckworth. Central Park: A History and a Guide. New York:Clarkson N. Potter, Inc. (1967): 30-36.

- ↑ Reed, Henry Hope, and Sophia Duckworth. Central Park: A History and a Guide. New York:Clarkson N. Potter, Inc. (1967): 36-51.

- ↑ Reed, Henry Hope, and Sophia Duckworth. Central Park: A History and a Guide. New York:Clarkson N. Potter, Inc. (1967): 40-41.

- ↑ Reed, Henry Hope, and Sophia Duckworth. Central Park: A History and a Guide. New York:Clarkson N. Potter, Inc. (1967): 46-47.

- ↑ Reed, Henry Hope, and Sophia Duckworth. Central Park: A History and a Guide. New York:Clarkson N. Potter, Inc. (1967): 48.

- ↑ Reed, Henry Hope, and Sophia Duckworth. Central Park: A History and a Guide. New York:Clarkson N. Potter, Inc. (1967): 48-49.

- ↑ Reed, Henry Hope, and Sophia Duckworth. Central Park: A History and a Guide. New York:Clarkson N. Potter, Inc. (1967): 50-59.