Major Themes of the Italian Immigrant Experience

Overview

The United States is commonly referred to as the melting pot, a place where people from different ethnicities amalgamate to form one, cohesive nation. Throughout American history, people have immigrated to this country from all across the world and then, consequently, assimilated into American culture. The Italian Americans are one such group. The Italians arrived in the United States in great numbers in the nineteenth century and later became the fourth largest ethnic group in the United States. We were interested in studying how the Italians’ unique experiences, achievements, and trials as immigrants continue to have an impact on the lives of present day Italian Americans.

Specifically, the steadfast traditional values of Italian immigrants determined their course towards assimilation and mobility in the United States. Family and neighborhood dynamics played a crucial role in the Italians’ success in navigating the American institutions pertaining to education, religion, and politics. Later, second generation Italian American preserved the group’s ethnic identity by continuing to celebrate aspects of Italian culture. Italian American youths developed their own vibrant subculture, as an expression of their Italian heritage and also in response to the forces of assimilation present in American culture. The “Guido” continues to flourish amongst youth in predominantly Italian neighborhoods such as Howard Beach. The information presented here is our conclusions based on scholarly literature pertaining to the Italian American experience.

Neighborhood Dynamics and Family Life

In order to understand the experiences of present-day Italian Americans, we must first examine the Italian immigrant experience. Beyond the Melting Pot, which, in the 1960s, was considered one of the definitive works on minorities in New York City, illustrates the numerous obstacles the Italians faced. The majority of Italians that settled in New York were of South Italian origin. In Italy, the Southern Italians were perceived as inferior peasants due to their economic situation and illiteracy. They stayed within the confines of their own village and anyone outside of the family was considered a stranger.

This mentality permeated the Italians’ experience in America. Accordingly, the immigrants assembled with others from the same village. Many of the married sons and daughters stayed close to their parents. Parents felt children should contribute solely to family advancement—therefore, education was not emphasized. This put Italian-Americans at a disadvantage in terms of job outlook and career success. Instead of going to some distant city or town to practice their profession, professionals from the later generations went back home and became the community doctor, lawyer, etc. Only in the past few decades have children been able to really break free from their communities and do as they wish. Nowadays travelling abroad and working on Wall Street are viable options. Despite this fact, there is still this sense of loyalty to the community that survives even to today.The bonds that existed between Italian immigrants led to the creation of small, insular communities. To this day, neighborhoods such as Howard Beach, which are heavily populated with Italian American, continue to flourish. In these microcosms of society, Italians were able to gradually move up the social ladder. They did the jobs that were needed in their neighborhoods and opened up businesses to meet the needs of the community. Today, many Italian Americans choose to stay in neighborhoods such as Howard Beach because their entire community, from their family members to their social networks and business connections, are based in that one neighborhood.

Howard Beach, New York, is located in the southwestern portion of Queens. Much like other neighborhoods in Queens, Howard Beach is comprised of smaller neighborhoods. These include: Howard Beach, Hamilton Beach, Ramblersville, Rockwood Park, Lindenwood, Old Howard Beach, and Howard Park. Unlike the rest of New York City, where Italian Americans make up only 2% of the population, nearly half of Howard Beach's population is Italian American. To read more about the neighborhood, including relevant statistics, please visit: Statistics

To read more about neighborhoods in the context of our focus, Howard Beach, please visit this link: neighborhood.

Youth Culture

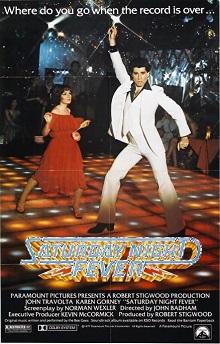

One of the most interesting aspects of life in Italian American communities is the prevalence of a specific youth subculture whose members are known as guidos. The word comes from a derogatory slang term that has since been reclaimed by Italian American youths. In Guido: An Italian American Youth Style, the author examines how the Guido subculture does not “embrace traditional Italian culture nor repudiates ethnicity in identifying with American culture” (Guido 42). Rather, guidos merge aspects of their Italian heritage with the pop culture and fashion that epitomizes American culture. For young Italian Americans, being Italian is something that is intrinsically associated with a certain style – gelled hair, gold jewelry, and imported Italian clothes – and a certain attitude – street-smart, macho, and intimidating. The Guido identity, like most other youth subcultures, has everything to do with social acceptance; it “is a highly valued personal attribute that is rewarded with peer group popularity” (Guido 51). Guidos are scene-setters. Their fashion and their music has permeated the mass media. Being Italian and being a Guido is “in.

The Guido youth culture challenges the typical narrative of an immigrant experience in the United States. Most immigrant groups when the first come to America are stigmatized for clinging to the values and traditions of their own culture. As a response, their American-born children slowly move away from their roots and become more Americanized, or assimilated. Guido culture is characteristically practiced by Italian youths who embrace Americanization whilst proudly portraying themselves as Italians. We were interested in learning how the culture of Italian immigrants became an acceptable or desirable way of life for some youths. Today, through the propagation of negative stereotypes by shows such as Jersey Shore, the guido youth culture is mocked and parodied. We were interested in learning the origins of the guido youth culture, the importance it holds to Italian Americans, and finding a more thorough definition of what it means to be a guido.

The conclusion we drew was that, in an enclave such as Howard Beach, where the community is connected by its homogeneity, the youth, by default, would take pride in their culture. Italian American youth are more inclined to find a connection to their heritage, but instead of simply accepting the Italian identities of their parents, they are trying to discover what it means to be Italian for themselves. Furthermore, as Italian-Americans began to move up the social ladder and became middle class, the overall Italian culture became sophisticated. The 1980 publication of Attenzione featured Italian culture, targeting middle class families (Ethnic 28-29). With the acceptance of Italian culture, a richer and more luxurious lifestyle was desired. This lifestyle trickled down to the younger generations of Italian-Americans. It became necessary to flaunt their wealth through material possessions such as gold jewelry and luxury class cars. Finally, the media and American pop culture had a huge effect in shaping the identities of Italian American youths.

To read more about youth culture, please refer to these links: introduction-guido-culture and influences-italian-american-teenagers.

Issues of Race

When immigrants from southern Italy first arrived, they fascinated “white Americans”. Because of their olive skinned complexion it was hard to categorize them as either “white” or “black,” the “only two possibilities in the domestic racial taxonomy” (Orsi 314). Immigrants from northern Italy saw the southern Italians as outsiders and often used “racist categories” (i.e. labeling southern Italians as “Turks”) to differentiate themselves. Because the immigration of southern Italians to America coincided with the migration of African Americans, African Caribbeans, Puerto Ricans, and Mexicans to the north, Italians were considered part of the “first wave of dark skinned immigrants” (Orsi 316). As a result they found themselves increasingly categorized into the latter category as “blacks.”

Italian immigrants were determined to lose the label of “Turks” and to become “cristiani,” which meant “human beings.” This further illustrated how negatively they perceived that label and sought to rid themselves of it. In order to do this, they realized that they needed to cut off their association with the “dark-skinned other.” This idea manifested itself in the immigrants’ realization that “in order to survive they had to ‘look with loathing upon everything the native whites loathed,’” which encompassed African Americans as well as other immigrants who were considered “colored.”

In the 1969 mayoral campaigns, race placed a huge role for all three candidates, incumbent John V. Lindsay, Mario Procaccino, and John Marchi. During the campaign, Lindsay “branded” Procaccino, an Italian-American candidate, as a racist and “anti-black.” The author notes that interethnic racism existed between white ethnic groups; in “dismissing” Procaccino and his supporters as racists, Lindsay both masked the racism his own supporters held towards Italian-Americans and simplified the “very nature of race.” Under Lindsay’s oversimplification, New Yorkers were either whites or minorities, pro-minority or racists.

Howard Beach came to the nation's attention when teens were accused of assualting three black men, resulting in the death of one of those men. Newspapers across New York and the country covered it; Al Sharpton organized a protest in Howard Beach. However, Senator Jermey S. Weinstein sought to disprove the claim that all Italian-Americans are racist. In an Op-Ed in the New York Times, he wrote, “the citizens of an entire neighborhood were tried, and convicted, for a crime they did not commit,” even though many, “vehemently condemned the violence.”

To read more: Race and Ethnicity

Media Representations

To read more about how the media portrays Italian Americans, please read: Media Representations

Works Cited

Albergotti, Reed, Thomas Zambito, Marsha Schrager, and John Rofe. "The Queens Spin - The Howard Beach Case." Queens Tribune. Web. 23 Feb. 2010. http://www.queenstribune.com/anniversary2003/howardbeach.htm.

Eichenwald, Kurt. "If you’re thinking about living in Howard Beach - New York Times." The New York Times 27 July 1986. The New York Times - Breaking News, World News & Multimedia. Web. 25 Feb. 2010. http://www.nytimes.com/1986/07/27/realestate/if-you-re-thinking-of-living-in-howard-beach.html.

Lizzi, Maria C. ""My Heart Is as Black as Yours": White Backlash, Racial Identity, and Italian American Stereotypes in New York City's 1969 Mayoral Campaign." Journal of American Ethnic History 27.3 (2008): 43-80. Web. 29 Apr. 2010.

Orsi, Robert. "The Religious Boundaries of an Inbetween People: Street Feste and the Problem of the Dark-Skinned Other in Italian Harlem, 1920-1990." American Quarterly 44.3 (1992): 313-47. JSTOR. Web. 26 Apr. 2010. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/2712980>.

Tricarico, Donald. "Youth Culture, Ethnic Choice, and the Identity Politics of Guido." Voices In Italian Americana 2007: 34-86. Voices in Italian Americana. Web. 25 Feb. 2010. www.niaf.org/public_policy/images/Guidos-and-Guineas-final.pdf.