Park Slope: 3rd StreetFrom The Peopling of New York City

The BlockThird Street between Fourth and Fifth Avenues IntroductionThird Street between Fourth and Fifth Avenues in Park Slope, Brooklyn, is a particularly interesting block because it contains so many different kinds of buildings and spaces: a park and playground, two restaurants, a handball court, a dog park, brownstones, condominiums, and, most significantly, a historic landmark. Amidst the commercial buildings, residential buildings, and recreational spaces, the Old Stone House stands out as a clearly different kind of building. To those who do not know immediately that the house is a historic landmark, it is at least clear that it is not one of the traditional Park Slope brownstones, that it is a far cry from the condominiums across the street. The Old Stone House, though since reconstructed, is the lone survivor of the key role this block played in the Revolutionary War, long before it was Third Street between Fourth and Fifth Avenues. As I commenced research on the House’s history, I have found it fascinating to discover not only the colonial history of the building but also the way it has changed hands and uses over the years. As I have developed my focus in this research project, I have decided to provide a preliminary understanding of the rest of the block, with particular interest in J.J. Byrne Park, not only because it surrounds the house, but also because it allows me to focus primarily on the Old Stone House itself and the people who bought and sold it, reconstructed it, and put it to different uses over it’s 310-year history. When you first approach Third Street, coming down from Sixth Avenue towards Fifth Avenue, you see on your left-hand side Byrne Park, which includes a small grassy area and a playground, complete with swing set and sprinkler. As you walk past Byrne Park, you begin to see the Old Stone House emerge. The historical building is followed by a large ball court and dog park. The end of the street leads you to the large Fourth Avenue intersection, where you begin your ascent back up to Fifth Avenue, along the other side of the street. The corner building is Elements, a hair salon. Then the condominiums begin, followed by a number of brownstones. The last two buildings on the block are restaurants: Villa Rustica and The Stone Park Cafe.

Youtube got rid of the sound, and the video is a little rocky, but you can see most of the buildings on the block, and the park, etc. Video taken by me on March 11 2009.

The Old Stone HouseWhen the Vechte family emigrated to New York from the Netherlands in the 17th century, they purchased the land that would one day become 3rd Street between 4th and 5th avenues. In 1699, the Old Stone House was built, and almost eighty years later the house played a key role in the Battle of Brooklyn in the Revolutionary War. Toward the end of the 18th century, the Vechtes sold the house to the Cortelyous, who eventually sold the land to a developer by the name of Edwin C. Litchfield. No longer a residential building, the house was used for a Brooklyn baseball team's clubhouse and the grounds used for a park and skating rink at the end of the 19th century. But before long, the house was knocked down and its foundations buried. When the Old Stone House's remains were recovered in the 1930s, reconstruction soon began. It would be years, though, before the new Old Stone House was historically recognized and began to be utilized in the way it is today. The following history attempts to uncover not just the history-the war, the reconstruction, etc-but the people who lived in the house, how and why they let go of the land, and what they did there. My research begins in the 1630s and takes me to the present day, where the house stands on a block with condominiums, brownstones, restaurants, a park, a handball court, and a hair salon, centuries away from the farm of the Vechtes. By observing the prosperity, the grief, the deaths, and the raising of families that occurred here I hope to transform a history into a human experience.

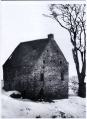

A History of the House In Images

Before the VechtesSixty years before the Vechtes built their house on their newly purchased farmland, the land that would eventually become Third Street played a key role in the aspirations and lives of a number of Dutch immigrants. The story of this block thus begins with a number of early colonial stories and transactions, most of which I unearthed through my research at the Old Stone House itself. The first owner of the land that would someday contain the Old Stone House was Jan Cornelissen Van Rotterdam. He owned the land in 1637 or 1638, but presumably did not actually use the land. He was killed by Native Americans in 1643. [11] The next owner of the land was Thomas Beeche, an Englishman from Massachusetts. He bought the farm in 1638 and sold it on May 17, 1639. Van Rotterdam and Beeche both owned adjacent tobacco plantations in Manhattan as well. Beeche was in a great deal of debt, and owed mortgages on all of his farms/properties, further exacerbated by his unruly wife, Nan. Sometime between June 8, 1640 and July 10, 1640, Beeche either died or disappeared. [12] Beeche had already sold the farm to Cornelius Lambertsen Cool at this point, however. Cool payed 300 guilders (equivalent to 120 silver dollars) to Beeche for the property. On the same day that Cool bought the land, he also bought two cows, so we can assume he intended to use the land for a farm. In 1643, Native Americans in King's County burned a great deal of land and houses due to a provoked war, and Cool died in the attack at age 55. [13] On January 5, 1644, Cool's wife Aeltje signed an agreement with Gerrit Wolphertsen Van Couwenhoven and Claes Jansen Van Emden (her stepsons-in-law) in order to divide the estate. The farm was in ruin at this point, presumably because of the attacks. [14] The house then passed on to Cool’s heirs, but because the deed has never been found from when the Vechtes purchased the land, we do not know what year or who exactly was involved. [15] We do know, however, that some time between 1660 and 1689, the Vechte family purchased the land on which they would build the Old Stone House. [16] The Vechtes (including the Battle of Brooklyn)The Vechte and Cortelyou families are the two most associated with the House, as it is often referred to as the Vechte-Cortelyou house. The story of the Vechtes is such a rich part of the history of the Old Stone House both because they were the family that built the original House and because they were the first family to pass the property down through a number of generations, creating an intricate family story on these very grounds. The Vechte family came to New York from the Norg, in the Province of Drenthe, in the Netherlands. The family was originally from the Province of Utrecht in the Netherlands. Claes Arentsen Vechte came to America on a ship called the Spotted Cow, leaving the Netherlands on April 15, 1660 with his wife (Lummetje Hendricks) and three children (ages 6 years, 4 years, and 9 months), and another boy of 14, who was presumably a servant. The only children mentioned in subsequent records are Hendrick and Gerrit Vechte. [17] Once in America, Lummetje gave birth to another child, Arent, who died when he was still a baby. Records show that he had a horse and seven cows in 1675, as well as 28 acres of cultivated land. In 1676, he had one horse and eight cows, and in 1683, he had eight cows and no horse. In 1683, his son Hendrick Claessen Vechte was living with him, while his other son Gerrit Claessen Vechte was living in Staten Island. It was either Claes or Hendrick who built the Old Stone House in 1699. [18] The House was one of the largest in the area at two and a half stories, because most were single story buildings. [19] It is not known when Claes died, but the last record of him is in 1698. It is generally assumed that he was alive when the house was built, but he did not leave a will, so all we know is that Hendrick either built it himself or inherited it from his father, without an official will.[20] The House was "constructed mainly of stone, the gable-ends, above the eaves, being of brick; the date of its erection, 1699 , being indicated by iron figures secured" on the side. [21] Thus, Hendrick Vechte is the key figure in the first years of the Old Stone House. Hendrick was born in either 1654 or 1656 in the Netherlands (I gather historians are not sure whether he was the 6 year old or the 4 year old recorded on the boat voyage to America). He was confirmed as part of the Brooklyn Reformed Church in 1677 and married Gerritje Reyniers Wizzelpennig in 1680 at the Flatbush Reformed Church. Hendrick had six children baptized with Gerritje (any number of children could have died as infants and been unrecorded, which was not uncommon: Hilletje (born in 1684 and married to Heironemus Rapalje), Jannetje (born in 1687 and married to Pieter DuMont), Lummetje (born in 1693 and married to Pieter Staats), Gerritje (born in 1696), Reynier (1701-1758, married to Jacomyntje Van Duyn), and Nicholas (Dutch equivalent of Claes, 1704-1779, married to Cornelius Van Duyn).[22] (On a side note, some of my research leads me to believe that some historians and newspapers have confused Nicholas Vechte as the builder of the Old Stone House, but given that he was born five years after it was built, this is clearly impossible. It is really interesting to see how the actual records and more reliable accounts I have now read run contrary to some of the information I found in Eagle, NYT articles, etc.) Hendrick was appointed a Justice of the Peace by King William III in 1698, and owned lands in Bedford and Gownaus. He was a carpenter, a wheelwright, and a farmer, and owned three slaves. He was reportedly wealthy. Hendrick died at the Old Stone House on December 7, 1716, and his widow followed suit on November 9, 1754.[23]  Map of Brooklyn, 1766. The box shows where the house/farm were. [24] Nicholas Vechte is the only one of the children of Hendrick and Gerritje who factors into our story significantly, because it was he who inherited the house from his parents. While the rest of Hendrick’s offspring moved westward, or to New Jersey where his brother’s descendants also lived, Nicholas remained in the house until his death.[25] Nicholas had a number of children, but many of them died in infancy. Only two daughters survived to adulthood: Machteltje III (Machteljes I and II both died before turning 2) and Gerritje. His son Hendrick died at age 10. Machtelje III married Rem Cowenhoven (1724-783), but died at age 32, in 1771. Gerritje survived the longest; she was born in 1727 and married Folkert Duryea, who died in 1752. She then married Teunis Tiebout in 1754. All of these children lived in the Gowanus area. According to census records, Nicholas also had about three slaves.[26] Nicholas Vechte dug canals on his property in order to transport produce to Manhattan. He also bought a strip of land running through Red Hook from north to south, on which he and his neighbors dug a six foot ditch, which became a canal and provided a shortcut from the Gowanus Creek to the East River. [27] Nicholas reportedly dug a canal that came directly from his kitchen door. Later, because the tides made the water supply sometimes scarce, he dug a channel to a water gate. He would apparently get in his boat, raise his paddle, and his slaves in response would raise the gate and the floods would come in, bearing his boat along the creek. Described as a man of "eccentricity and independence," Nicholas appears to have derived pleasure from his clever schemes that put him one above his neighbors. [28] Nicholas Vechte was in the Old Stone House during the Battle of Brooklyn, and undoubtedly his reaction to it would be interesting to hear firsthand. Vechte remained loyal to the king throughout the war in written documents, but it is unclear whether he actually supported the king or was coerced into singing petitions for restoration of British influence in America.[29]  Plaque commemorating Battle of Brooklyn, original photograph in Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn Public Library Collection.[30] The Battle of Brooklyn began on August 27, 1776. On this day, the Maryland 400, under command of General William Alexander, fought against the British General Cornwallis’s troops. The British army occupied the Vechte-Cortelyou house in order to shoot at American troops crossing what was then known as Gowanus Creek. By holding off Cornwallis’s troops, Alexander’s men made it possible for George Washington’s army to make it across the Gowanus Creek. They assaulted the house six times to make this escape possible. The Maryland brigade did briefly drive the British out of the house, but British reinforcements caused destruction for the American army. The number of deaths for the Americans amounted to 250 men. [31] It is important to note that over time many people have wrongly believed that the Old Stone House was the site of General George Washington's headquarters during the war, which is entirely false. Washington went to the site after the Battle of Long Island took place, but his headquarters were supposedly in Manhattan. The history does, however, mention an unidentified writer said, "the British had several field-pieces stationed by a brick house, and were pouring canister and grape on the Americans crossing the creek." This statement presumably refers to the Old Stone House and the Battle of Brooklyn. [32] Following is a more vivid account of the battle from a history of Brooklyn written by Henry R. Stiles: "Stirling , finding that he was fast being surrounded, saw that his only chance of escape was to drive Cornwallis , who then was occupying the "Cortelyou house" as a redoubt, up the Port Road towards Flatbush , and by getting between him and Fort Box , on the opposite side of the creek, to escape, under cover of its guns, across Brower 's mill-dam.* He knew that his attack upon the earl would, at all events, give time for escape to his countrymen, whom he saw struggling through the salt morasses and across the narrow causeway of Freeke 's mill-pond...Driving the enemy's advance back upon the stone house, from the windows of which the bullets rattled mercilessly into their ranks, they pushed unfalteringly forward, until checked by a fire of canister and grape from a couple of guns which the British hurriedly wheeled into position near the building. Even then they closed up their wasted ranks and endeavored to face the storm, and again were repulsed. Thrice again these brave young Marylanders charged upon the house, once driving the gunners from their pieces within its shadow; but numbers overwhelmed them, and for twenty minutes the fight was terrible." [33] Stiles' description of the battle reflects the goal of the Maryland 400: to protect their fellow soldiers despite the dangers they faced, particularly with the British occupation of the House. The map to the right shows the path of both armies throughout the battle.  Map of the Battle of Brooklyn, courtesy of theoldstonehouse.org [34] The presence of the British in Brooklyn was difficult for the farmers, as soldiers took property, livestock, and firewood. The soldiers would sometimes resort to burning fences and trees. Rem Cowenhowen, Nicholas Vechte's son-in-law, was a Patriot and member of the Kings County Committee of Safety. During the British occupation of Brooklyn, Rem changed allegiance and dissolved the Committee. He became a captain in the Kings County Loyalist Militia after the Battle of Brooklyn took place. Rem died on January 15, 1783. [35] While many farmers experienced devastating loss in the time before, during, and after the Battle of Brooklyn, Nicholas Vechte made it through with most of his property in tact, despite the occupation of his house. His will mentions seven different slaves by name (Mink, Bet, Frank, Tom, Nan, Hannah, and Gin). It also speaks of six cows, three horses, a cider mill, sleighs and wagons (one painted blue), a Dutch cupboard, and a small blue-painted cupboard." The farm itself, which he referred to as his "Old Farm or Plantation," and which included "wood lots, meadows, a salt meadow, a creek, a pond, and oyster bed," went to his grandson. [36] Nicholas Vechte died on September 9, 1779 and was buried on the farm (though it appears that he was buried between 5th and 6th avenues, rather than between 4th and 5th). At this point, the farm passed on to Nicholas R. Cowenhowen, who was only eleven-years-old and had to lease the farm to his aunt Gerritje Tiebout, until he was old enough to take the farm.[37] The story of the graves of Nicholas and his family is an interesting one. Though Cowenhowen and Cortelyou (who purchased the farm from him) preserved the graves, it appears that Edwin C. Litchfield (discussed later) did not pay any attention to them once he purchased the land in the mid-19th century. By 1873, the tombstones had been vandalized and only four remained, located on 5th Avenue between 2nd and 3rd Streets. A few years later, not even these tombstones remained. When the house was reconstructed in the 1930s, the developers did not acknowledge that there were bodies buried there, probably because they actually had no right to that land, seeing as it was separated from the property of the Old Stone House.[38] The CortelyousThe second (and only other) family to inhabit the Old Stone House and truly create a family story within it was that of the Cortelyous. Nicholas R. Cowenhowen inherited the house in 1779 from Nicholas Vechte and sold in to Jacques Cortelyou in 1790 for 2,500 pounds. Cowenhowen excluded the land on which his family was buried when he sold the farm. The Cortelyou name would have been well known at the time. Jacques' great great grandfather acquired Nayack in 1650s and owned a home in New Utrecht, which Jacques Cortelyou inhabited with his brother, both of whom were Loyalists. During the war, they signed allegiance to the king and were kidnapped by patriots in 1778 and held in New Jersey. Jacques continued to live in New Utrecht after the war and bought the Old Stone House for his newly married son Peter J. Cortelyou. [39] The Cortelyou family history merged with Brooklyn history in 1652, when Jacques Cortelyou (not to be confused with Peter's father) emigrated to New Utrecht. He was a well-known surveyor. According to "A History of the City of Brooklyn," Peter J. Cortelyou was six generations removed from the original Jacques Cortelyou. [40] Peter Cortelyou was born in 1768. At age 21, he married Phebe Voorhees and moved into the House the following year. According to the Federal Census of 1790, they moved in with two 16-year old white males, one white female, and four slaves. The census of 1800 lists the following members of the household: a white males aged 26-45, a white male aged 10-16, 2 white males younger than 10, one white female older than 45, a white female aged 26-45, a white female younger than 10, eight slaves, and two other free people. We can assume these additional people were relatives, boarders, servants, etc. The Cortelyous 4 children: Adrian Voorhees (1790-1872), Maria H. (born in 1792 and married to Simon Cornell), Jacques (1796-1891), and Timothy Townsend (1800-1803). [41] In 1802, Phebe died, and the following year, the youngest son Timothy drowned in a nearby pool. Peter remarried in 1803 to a woman named Mary Alstyne, and had a child named Phebe in 1804 (who lived until 1841 and married Daniel Lawrence Rapelje). The same year Phebe was born, Peter, still upset about the loss of his wife and son, hung himself on a pear tree behind the house. [42] Eleven years later (1815), Peter's son Jacques inherited the Old Stone House. The farm itself was split between Jacques (southern half) and Adrian (northern half). Jacques served with the 64th Ne York Militia Regiment during the War of 1812, and married Ann Maria Fowler in 1830, who had previously been married to a George D. Davenport. Together they had three children: Adriana (1831-1882), Caroline Amelia (1833-1912, who married Merwin Rushmore), and Lawrence Voorhees (1837-1896). When Ann Maria died in 1852, Cortelyou sold the house to Edwin Litchfield (due to increased property value) and moved to Dutchess County. He died there in 1891, and his entire family is buried in Green-Wood Cemetery. With respect to the family preceeding him at the Old Stone House, Cortelyou again excluded the burial grounds from his sale, continuing to preserve the space for the Vechtes. [43] After the CortelyousA significant chapter of the Old Stone House is closed here, because Litchfield was not going to care for a farm or raise a family on the grounds; he was a renowned developer. A history of the Old Stone House and surrounding farm from 1852 forward reveals a number of changes but minimal occupation of the actual House by residents. The first occupant of the House after the Cortelyous left was an African American caretaker. [44]Also, during the 1850s, streets were built around Washington Park and the Old Stone House at approximately fifteen foot high embankments, leaving the Park and House in basins. The first reference to Edwin Litchfield that I was able to find was in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, in an 1846 documentation of his limited partnership in a business intended for the “manufacture and sale of Sperm and Lard Oil and Sperm and Stearine or Adamantine Candles.” The small article says that Litchfield put twenty thousand dollars “towards the common stock” in the business, an indication that he was a man of considerable wealth. [45]  Edwin Litchfield's grave in Green-Wood Cemetery [46] Litchfield is a fascinating figure in local history, because he owned so much land in what is now Park Slope and thus ended up being a really significant figure in shaping the Park Slope we know now. His legacy survives in the mansion he had built in Prospect Park, designed by Alexander J. Davis and shown to the lower right in a photograph from the Brooklyn Historical Society archives. By looking at the 1860 federal census, I was able to learn some details about Litchfield's life. He was born around 1815 in New York. The value of his personal real estate in 1860 was $30,000, while the value of his total real estate was $300,000. He is listed as a lawyer. There are ten people listed as members of his household, though many do not have the last name Litchfield. [47]Based on my earlier findings with the Vechtes and Cortelyous, I would venture to say these other people were servants, though they could be in-laws and married children as well. The 1880 census reveals that he was married to Grace H. at this point, who is listed with Keeping House as her profession. He is now listed as "Real Estate" under profession, as is his son, Henry P. Litchfield, who was born in 1850.[48] Litchfield is buried in lot 23310 in Green-wood Cemetery, section G. He was buried on September 16, 1885.[49] A December 1887 article in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle by H.J.S. reveals that the House was originally known, by iron markers on the exterior, as “1699,” the year it was built.[50] These markers were removed in the mid-1850s. Though the article cites “unknown parties” as those responsible for the removal, I would postulate that any change to the house in the 1850s related directly to Litchfield’s purchase. Apparently Litchfield began developing the area in an attempt to make his property on Third Avenue connect to his mansion on Prospect Park West.  The Litchfield mansion in Prospect Park c.1870 [51] In 1861, the house was used as a clubhouse for the Washington Skating Club and was the first private rink in the city. At some point in the 1860s, the house was also apparently being used as a stable, and a Mr. Stilos, unidentified in Brooklyn Eagle article beyond his name, described it as “destined soon to disappear.” However, when this article was written, the house was naturally still standing, though it had undergone some changes: “the high roof and domer windows” were replaced by more modern counterparts and inside partitions of the building were removed." The writer of the article celebrates the fact that the Vechte-Cortelyou house would probably be standing long after the more modern buildings around it fell. After the Battle of Brooklyn, the house and surrounding area was titled Washington Park. In 1887, the house stood in the northeast corner of the park. At this time, C.H. Ebbets was general superintendant of the park, and William Windram was ground keeper. The writer of the article says that the house is commonly misconceived as Washington’s headquarters, though Washington did not arrive at the scene until the battle on August 27, 1776. [52] During the 1880s, the pre-Dodgers Brooklyn baseball team, the Bridegrooms, used Washington Park as a baseball field, and the house consequently became their clubhouse. The team's first game, and the opening of Washington Park, took place on May 12, 1883, at which point the team was playing in the minor leagues. They won the Inter-State championship that year and went on to play in the Major leagues in 1884. Charles H. Byrne was the original coach and owner of the team. In 1887, Byrne merged the Mets and the Dodgers, and in 1889 the team won their first pennant. They played in the World Series against the New York Giants and lost. The following year, the team switched to the National League and played in the World Series against the Louisville Colonels. Original Washington park ticket taker Charles H. Ebbets became coach in 1898, though the team had left Washington Park at this point. [53]At some point after the team moved in 1891, the house was destroyed (probably in 1897) and its foundations buried as city planners made way for continued development on what is now Third Street. [54] Pictures of the baseball field and skating rink are available on my images page, linked above. The ReconstructionFor years after the foundations of the Old Stone House were buried, no one had any idea that an important historical building had been lost amidst the rubble. The rediscovery of the grounds and the subsequent reconstruction began a new chapter in the history of the land. The foundations of the Old Stone House were rediscovered in 1930, when it was rebuilt. Then-Parks Commissioner Robert Moses used $750,000 for the restoration ordered by the Borough President, J.J. Byrne (more on him below). The reconstruction, 75 feet from the original house and now in the center of the park, was completed in 1934, and was used, in the words of the Parks Department, as a “park office and comfort station.” The house was not, however, an official historic landmark at this time. [55] Horrified by the way the Old Stone House had been used since the Revolutionary War, Brooklyn residents John Gallagher and Herb Yellin decided in the 1980s to take steps to give the building its rightful place in history. The First Battle Revival Alliance was created in 1988 by Gallagher and Yellin in order to work toward restoring the house, a goal that was achieved eight years later when the Alliance received a $750,000 grant, interestingly equal to the funds allocated to rebuild the house sixty years earlier, from the office of Howard Golden, Borough President. The New York City Department of Parks and Recreation describes these 1996 changes to the Old Stone House as improvements in windows, roofing, finishing, and various new electrical and plumbing systems. [56] A year after the 1996 refurbishments, the Old Stone House opened as a museum with educational programs, maintained by the Parks Department. Promotional material for the Old Stone House advertises a sample of the educational classes now offered there, with go for $90 per 90 minute class. Classes for students ranging from Pre-K to 12th grade include Dutch Toys and Games: Work and Play - A Child´s Life in Colonial Brooklyn, The First Battle for American Freedom: Understanding Brooklyn´s Unique Role in the Revolution through Maps, A Sense of Place: OSH History through Primary and Secondary Source Documents, Searching for Freedom: African Americans in the American Revolutionary War Era, Pinkster: An African American Celebration, From Many One: Colonial and Revolutionary Currency, and From Many One: Colonial and Revolutionary Flags. Educators from the Old Stone House can also visit classrooms for a $130 fee. The Old Stone House has “historical exhibits open to the public,” and is currently available for rentals, with certain rules and allowances about food, alcohol, etc applying. [57] When I was there, for example, the top floor was closed off for a one-year-old's birthday party. The story of this House covers residents, soldiers, farmers, developers, builders, baseball players, ice skaters, borough Presidents, historians, and activists. From the physical labor of farming to the intellectual pursuits of history, the purposes of the House have transformed rapidly over the years, creating an intricate history of people and events. Byrne/Washington Park Byrne Park in the 1950s. Brooklyn Public Library Collection. [58] The Old Stone House is situated in what is currently known as Washington Park, though commonly still referred to as J.J. Byrne Park. 120 years ago, this park was known as Washington Park, but until recently is was known as J.J. Byrne Park. The name Washington Park demonstrates verbally the connection between the park's (and formerly the farm's) relationship with colonial history. Washington Park is a 3.03 acre park that consists of a playground, handball court, dog run, and the Old Stone House. The playground still bears the name of J.J.Byrne, who was elected borough president of Brooklyn in 1926 (the same year Byrne Park was acquired by the Parks Department) and died in 1930. Byrne was the borough president responsible for having the Old Stone House, then known primarily as the Vechte-Cortelyou House, reconstructed when its foundations were discovered in 1930. The Board of Aldermen named the park after him in 1933. Byrne Park was joined with William Alexander Junior High School 51 and its playground in 1951. [59] The name of the park was officially changed back to Washington Park in 2008, but out of respect to Byrne, the plaque with his name is still on the playground, so for many Park Slopers, myself included, his is the name associated with the park. The change in name apparently had a lot of support from the community and stems from the association the block has with Washington (and the Battle of Brooklyn). [60] In the interests of using this block to discover more about the people who have inhabited New York City, I have looked more deeply into the life of f J.J. Byrne, since he was a key figure in the reconstruction of the Old Stone House, though he died soon after its rediscovery. Byrne was born to Irish immigrant parents in 1863 in Brooklyn in waterfront district that, interestingly, was known as Irishtown at the time. Byrne was not educated past grammar school, working as a clerk and errand boy when he was young and eventually becoming a machinist for a rope and string manufacturer until he made a breakthrough in 1898. Because he scored well on his civil-service exam that year, he got a job as chief clerk of the Buildings Department in Brooklyn, and nine years later became chief clerk of the Bureau of Public Buildings. In 1918 he became superintendent of the bureau. He served in this position until 1926, when borough president Joseph A. Guider died in office.[61] Brooklyn members of the Board of Aldermen unanimously voted for him to take over the rest of Guider's term. [62] He won a special election in November, and in 1929 he won an official election to begin a full term as borough president. Under Byrne's presidency the public library and sewer systems were expanded, the Central Court Building and Municipal Building were completed, and the reconstruction project on the Old Stone House was begun. Byrne never saw its completion since he died of kidney failure in 1930. [63] The playground that is part of the park seems to be referred to as both Terrapin Playground and J.J. Byrne Playground. The land for the playground was secured by City Hall in 1948 through private purchase (after the Old Stone House had been reconstructed). The playground opened in 1951, and since it is next to M.S. 51, it is operated both by the Parks Department and the Board of Education. The name Terrapin was given to the playground in 1997 by Commissioner Stern to honor an inhabitant of Park Slope. [64] Reverting back to the name Washington Park was not the only change the park (and thus the block) has undergone in the last couple of years. Developers Leviev Boymelgreen financed $2 million worth of renovations in the park in a deal that allowed use of part of the park as a "staging area for a nearby residential construction project." [65] These changes included two new basketball courts, six renovated handball courts, and general landscaping improvements. Funds for a second set of changes include "$1 million from Councilman Bill de Blasio, $500,000 each from Councilman David Yassky and the Brooklyn Borough president, Marty Markowitz, and $83,000 from the mayor’s office." [66] These finances will allow for further re-landscaping and a view of the Old Stone House from Fourth Avenue made accessible. In 2010, a $1.3 million grant will get new equipment for the playground at Fifth Avenue. [67] Since plans for changes in the park are still ongoing, I thought it would be interesting to show what it will potentially look like in a few years. You have seen the Old Stone House in pictures from 1699 to 2009. Now see what this block will (maybe) look like in the future: As shown above, possible changes include a food kiosk (which may be run by the Stone Park Cafe), an annex for the Old Stone House, and a change in the front path and overall look of the block, including the view of the Old Stone House. [68] Washington Park has been a spot of much change in recent years, from the name to the physical nature of the pace, and more change is forthcoming. The Residential BuildingsWhile the Old Stone House is the point of attraction on this block, the buildings across the street are nevertheless intriguing. One impression that struck me as particularly interesting when I really began to observe my block in depth was the fact that the side of the street opposite the Old Stone House is a mix of commercial buildings and residential buildings, and that the residential buildings themselves are a mix of brownstones and condominiums--a dialogue between old and new and a fitting parallel to the old but new house across the street, built in 1699 but reconstructed in the 1930s. My first step in understanding the history of the residential buildings opposite the Old Stone House was to find out what the buildings are like now. A Brown Harris Stevens real estate listing for 305 3rd Street, one of the condominiums on my block, describes the condo as a 6-room "mint condition duplex home" with a list price of $1,299,000. The condo's description even uses its proximity to the Old Stone House as a selling point. 333 3rd Street is listed by the same company, though at a lower price ($599,000), while other condominiums on the block have listings on the site that have been removed due to sale. [69] Since my main focus has been on the other side of the street (the Old Stone House and Washington Park), I did not go greatly in depth in my research of the commercial and residential buildings. The stories behind these buildings would inevitably be very interesting, but the buildings themselves are not nearly as old and rich with history as the House opposite them. However, I did want to discover more about when they were built. It seems that most of the buildings on the block were built around 1920. In researching the houses on this block, I also found information about the houses on 3rd Street between 5th and 6th Avenues, most of which were built between 1920 and 1935. When I searched on the New York Times real estate site, I was able to find three recent sales on my block, which gave some basic information about the sites. Here are the three listed apartments sold in the last two years on my block: 1. 315 3rd Street Apt 1B, Co-op Built: 1920 Sales date: 4.14.08 Sales Price: $870,000

Apt 4C, Co-op Built: 1920 Sales date: 11.9.07 Price: $431,000

Apt 3A, Co-op Built: 1920 Sales date: 8.7.08 Price: $375,000 [70] As shown above, the price ranges clearly vary between even apartments in the same buildings, and between neighboring buildings. It appears that most of the buildings on this block are listed with Brown Harris Stevens or Corcoran Real Estate, and we can see a price fluctuation in the listed apartments on their sites as well. Since I did not find a wealth of information in city directories, I rounded out my research on the residential buildings by looking them up in the registry of the New York Department of Housing and Buildings. I looked up each address on the street and was able to view basic government information about the houses, work done on buildings, etc (most of which is not particularly relevant to telling a story about the street itself). What I did find interesting is that I was able to view Certificates of Occupancy for each building. Viewing the actual documents meant that I could see what year they were issued and how many people/families are allowed to live on each floor of each building. Here is some information from the "Property Profiles" found in the files of the Department of Buildings. 303 3rd Street: Certificate of Occupancy issued December 19, 1941. Walk-up apartment, 4 stories. Cellar: ordinary use. 1st floor: 1 family. 2nd-4th floors: 2 families. Total: 7 families. 305 3rd Street: Certificate of Occupancy issued March 11, 1966. 1 story, brick. 1st floor: 2 people, wholesale establishment, 15,000 sq feet. Now listed as condominium. 315 3rd Street: Certificate of Occupancy issued May 16, 1939, updated September 14, 1988. 4 stories. Cellar: ordinary use. 1st-4th floors: 2 families each. 8 families total. 317 3rd Street: January 24, 1989. 4 stories. Cellar: ordinary boiler room, meter room, recreation rooms. 1st floor: 4 apartments. 2nd-4th floors: 3 apartments. Total: 13 apartments. [71] These sources allow a snapshot of the residential life on this side of the street. As shown above, the buildings were mostly built around 1920, with the certificates of occupancy being completed a number of years later. The certificates reveal that most of the houses on the block have apartments designed to fit a number of families on each floor, ranging between seven and thirteen total. This research confirms my sense that the history of this side of the street (after it was paved and turned into a residential block) is not nearly as intricate in terms of how long these buildings have been here. The residential buildings are evidence of the way in which the world around the Old Stone House has developed, a process begun in earnest by Edwin C. Litchfield in the nineteenth century. The Commercial BuildingsThere are three commercial buildings on 3rd Street between 4th and 5th Avenues, all on the opposite side of the street from the Old Stone House. While it is easy to get lost in the rich history of the Old Stone House and Washington Park, the other side of the street is a reminder that this block is part of Park Slope as a whole, a very distinct neighborhood. Elements, the hair studio on the corner of Fourth Avenue, is a typical moderately expensive Park Slope salon, while Villa Rustica fits the prototype for a good Park Slope pizza place. Stone Park Cafe is hailed in reviews as an excellent dining spot for American food with a twist, fitting in perfectly with the Park Slope interest in good dining and family-friendly restaurants. By stepping back to look at these three buildings and businesses, we can see the block in a large context and introduce new themes: entrepreneurial spirits, the trials of real estate and business, and inevitable change. Elements hair studio is on the corner of 3rd Street and Fourth Avenue. The building address is 301 3rd St. Elements has served the Park Slope community for a number of years, but first in a different location, on Fifth Avenue between 2nd and 3rd Streets. Villa Rustica opened at 357 Third Street on October 13, 2008, replacing Pizza by the Park. It serves pizza and Italian cuisine. More information appears to be available about the Stone Park Cafe, which opened in September 2004. According to Frank Bruni of the New York Times, "It opened last September, the lovingly realized dream of two childhood friends, Josh Foster and Josh Grinker. Mr. Grinker supervises the kitchen with Tracy Young. All three learned their restaurant ropes elsewhere and are striking out on their own for the first time. They took a rundown bodega, broke through its rear wall to connect to a garage and then decorated the expanded space in a pleasant, modest fashion, making generous use of exposed brick and Brazilian cherrywood floors." [72] Bruni's account calls to mind an innovative spirit of entrepreneurship that is particularly appropriate to a block so richly steeped in the history of this country's first settlers. The Stone Park Cafe is the corner building, at 324 Fifth Avenue. Owner Josh Foster previously worked at Tribeca Grill, while chef/owner Josh Grinker previously worked at the River Cafe, before they teamed up to open the Stone Park Cafe. [73] A couple of years ago, when Pizza by the Park was still in existence, there was definitely a sense of cohesiveness among the different sites on the block, the Stone Park Cafe and Pizza by the Park being clear tie-ins with Byrne Park and the Old Stone House. Final ThoughtsThird Street between Fourth and Fifth Avenues in Park Slope is one of the most diverse blocks in the neighborhood, and perhaps in the city. This diversity comes not simply from the occupants but rather from the sheer variety of buildings and spaces on the block. A walk down the block reveals indoor and outdoor spaces, private and public buildings, historic landmarks and signs of the everyday. My goal through this research has been to unveil the stories of the people who have lived, worked, and died on this block, those who have started lives for themselves in a new world, sacrificed themselves in the name of revolution, played a good game of baseball, begun businesses, discovered the remains of an old building, and created a beautiful park and museum to pay tribute to the vast history beneath our feet. The Old Stone House in many ways encapsulates the essence of this country, with its early American families and key role in the Revolutionary War. Yet at the same time, it carries so many unique stories that have nothing to do with our unity as a country but everything to do with a sense of individuality and everyday life finding its place in history. The people who have carried out their lives on 3rd Street have simultaneously been part of a textbook kind of history and an individual kind of history, a relationship that I have tried to faithfully portray. Notes

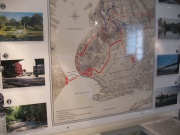

Bibliography"J.J. BYRNE ELECTED TO SUCCEED GUIDER; Brooklyn Aldermen Unanimous in Choice for the New Borough President. TO BE CANDIDATE AGAIN Democrats Will Name Him for Long Term -- Single Republican Votes With Majority Party," New York Times, October 1, 1926, 25, at http://www.nytimes.com. “Limited Partnership,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 5, 1846, 3, at http://eagle.brooklynpubliclibrary.org. Photography Collections. Brooklyn Historical Society. Brooklyn, New York. (Specific documents/photographs have full citations in the endnotes above.) The Brooklyn Paper. Brooklyn Dining Listings: Stone Park Cafe. http://www.brooklynpaper.com/sections/go/dining/guide/374/. Brooklyn Collection: Historic Brooklyn Photographs. Brooklyn Public Library. Brooklyn, New York. (Specific documents/photographs have full citations in the endnotes above.) Brown Harris Stevens. 305 3RD STREET / Park Slope. http://www.bhsbrooklyn.com/detail.asp?id=984599. Bruni, Frank. "RESTAURANTS; Where to Take Thoreau and Dr. Atkins," New York Times, March 30, 2005, at http://www.nytimes.com. Burbank, David R. Green-Wood Cemetery, New York City, New York at Museum Planet. http://www.museumplanet.com/tour.php/nyc/gw/37. Butler, Jonathan. Brownstoner: Brooklyn Real Estate and Renovation. http://brownstoner.com/. The City of New York. NYC Department of Buildings. http://www.nyc.gov/html/dob/html/contact/contact.shtml. Chan, Sewell. "No Offense Intended, J.J. Byrne," New York Times, December 3, 2008 at http://www.nytimes.com. Green-Wood Cemetery. Green-Wood: History of Green-Wood Cemetery. http://www.green-wood.com/index.php/gwc. H.J.S. “The Old Gowanus Road: Line of the Second Section to the Southerly Ending,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 11, 1887, 6, at http://eagle.brooklynpubliclibrary.org. Lewine, Edward. “1699 House Is Finally Historic,” New York Times, April 27, 1997 at http://www.nytimes.com. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Grace Hill for Edwin C. Litchfield, Brooklyn, New York (front elevation). http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/davs/ho_24.66.67.htm. NYC Department of Parks and Recreation. J.J. Byrne Park-Historical Sign. http://www.nycgovparks.org/sub_your_park/historical_signs/hs_historical_sign.php?id=181. NYC Department of Parks and Recreation. Old Stone House. http://theoldstonehouse.org/. NYC Department of Parks and Recreation. Old Stone House museum. New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. Terrapin Playground-Historical Sign. http://www.nycgovparks.org/sub_your_park/historical_signs/hs_historical_sign.php?id=8245. The New York Times. New York City Recent Sales Data. http://realestate2.nytimes.com/comparables/. Parry, William J. "Life at the Old Stone House, 1636-1852: A History of a Farm and its Occupants." New York: The First Battle Revival Alliance, 2000. Stiles, Henry R. A history of the city of Brooklyn : Including the old town and village of Brooklyn, the town of Bushwick, and the village and city of Williamsburgh. Brooklyn, NY, USA: Pub. by subscription, 1867-1870. http://ancestry.com/. United States of America. Bureau of the Census. Eighth Census of the United States, 1860. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1860. Roll: M653_767, 480. http://ancestry.com/. United States of America. Bureau of the Census. Tenth Census of the United States, 1880. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1880. Roll: T9_855, 135. http://ancestry.com/. |