From The Peopling of New York City

The Charles B. Wang clinic has been the primary health center for Chinatown since 1971 serving a 95% Chinese demographic.

The events on 9/11 seem to have greatly increased the number of respiratory problems in Chinatown. After the collapse of the WTC, lower Manhattan was subjected to a variety of toxic fumes and chemicals. Dr. Loretta Au, the head of pediatrics for the clinic, even said, “Air around [Chinatown] had a different smell” after 9/11. In order to determine whether this foul air was just pungent or actually harmful, Dr. Au referred me to the studies of a Dr. Anthony Szema. Dr. Szema studied 205 pediatric patients at Charles B. Wang clinic before and after 2001. He kept record of how many annual visits a child made, each child’s asthma prescription, and weekly doses of rescue inhaler among other things. From his studies, he discovered

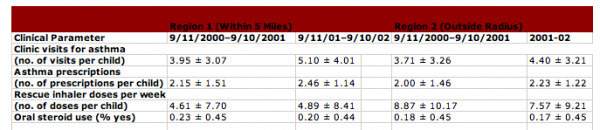

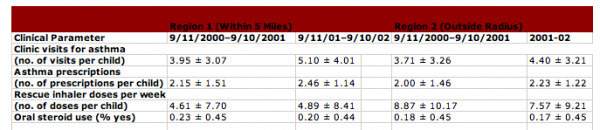

Asthma treatments in Chinese American pediatric patients treated at the CBWCHC, September 11, 2000–September 10, 2002, according to region of residence.

that after 9/11 patients had a significant increase in number of clinic visits. For example, before 9/11 patients had an average of 3.79 visits per year, whereas after 9/11 patients had an average of 4.69 visits for asthma per year (Szema 3). Also, before 9/11 patients were prescribed 2.05 asthma medications per year, whereas they were prescribed 2.33 asthma medications per year after 9/11 (Szema 3). In addition, Dr. Szema then divided the patients into two groups, one that lived within a five-mile radius of the WTC and the other outside of it. When he focused on the residential area of the patients, he found that patients within the five-mile radius had a significant increase in clinical visits: 3.95 per year before 9/11 versus 5.10 per year after 9/11. However, when Dr. Szema observed the group outside of the radius, he discovered that there was no real significant increase in clinical visits for asthma (Szema 3). Clearly something in the air from the WTC had been aggravating patients’ asthma conditions in Chinatown after 9/11. Subsequently, Dr. Szema began testing the air around Chinatown. Here he determined that the dust and fumes of the incident had left the air full of different chemicals. For instance, the air tested positive for calcium-based chemicals, which are known to irritate upper airways in humans. Overall, 9/11 caused more patients to come into the clinic for respiratory ailments.

The busy waiting room at the Canal St. Charles B. Wang Clinic. (Picture taken by Ericka Jaramillo.)

The events on 9/11 seem to have greatly increased the number of mental health disorders in Chinatown. However, tracking these effects on Chinatown’s mental health was difficult because “Asian Americans as a people respond differently to psychological needs,” explains Dr. Teddy Chen, the director of clinic’s Bridge Program, “If you don’t ask, they will not tell you.” Mental Health itself is a very vague aspect. Many Asian Americas who have a psychological disorder are not even aware that they have it because they have never heard of these “western” disorders before. Yet, the evidence supports that 9/11 has had a huge impact on the people’s psyche. For example, the number of encounters, which is the number of visits the mental health clinic receives, more than doubled the year after 9/11. In 2000, the number of patient encounters was 1,053, and in 2001, the number was 1,208. As one can see, the statistics were stable. Then in 2002, one year after the WTC collapsed, the number of patient encounters jumped to 2,755. Next year in 2003, the number increased to 3,611 patient encounters. This statistic then steadied in 2004 with 3,325 encounters. Clearly, the fall of the WTC had caused patients to come into the clinic more often.

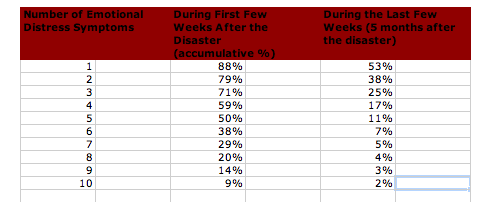

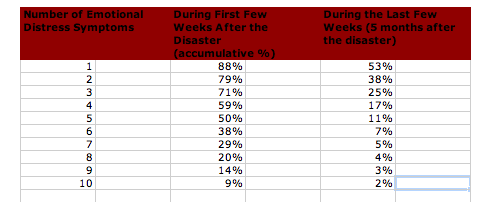

The total number of emotional symptoms immediately following and five months after the September 11th disaster (N=555).

Additionally, Dr. Hongtu Chen surveyed 555 Chinatown residents by asking them ten yes/no questions; including “Were you unable to have sad or loving feelings or feeling numb?” and “Did you lose interest or pleasure doing things?” He found that initially, 59% of the general residents had four or more emotional symptoms. After five months, these rates dropped to 17%. However, more than half of the community residents had consistently displayed one or more symptoms of emotional distress (Chen 1). Evidently, numerous new cases of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression among other things have been springing up to call for such a program in the clinic.

Questions for Assessing Emotional Distress

Previous Page

Next page