Views

Contents |

Sunnyside Gardens: The Housing Issue and the Lives of Immigrants

Introduction

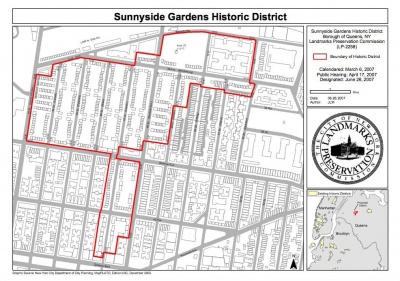

Sunnyside Gardens is a "planned community"[1] within Sunnyside that is bounded by Queens Boulevard, 43rd and 52nd Streets, and Barnett and Skillman Avenues. Built from 1924 to 1928, Sunnyside Gardens was the first "garden city"[2] in the nation and was designed by architects Clarence Stein and Frederick Ackerman, planner Henry Wright, and the landscape architect Marjorie Cautley, who were put to the task by the City Housing Corporation, which emphasized building "model neighborhoods."[3] [4] Inspired by the English Garden City movement of Ebenezer Howard and Raymond Unwi,[5] the designers wanted to create a "utopian"[6] community that would provide affordable suburban-like housing to working-class New Yorkers.

In order to achieve the goal of creating affordable housing on limited land while preserving the principles of "health, open space, greenery, and idyllic community living for all,"[7] Sunnyside Gardens' designers mapped out a solution that involved building "one, two- and three-family row houses" with inexpensive materials, and using what was "throwaway space"[8] to create common gardens and courtyards to facilitate community-building.[9][10]

The Making

Sunnyside Gardens, a residential development in Sunnyside, demonstrates the intersection of the issue of housing with the lives of immigrants. Established in 1924, the City Housing Corporation (CHC) founded the Sunnyside Gardens project in order to fulfill the views and goals of the Regional Planning Association of America (RPAA).[11] The RPAA wished to bring English “garden city”[12] ideals to housing development in the United States to address the country’s simultaneous problems of lack of affordable housing and lack of existing quality housing that promoted “a healthy and sane community life”[13] for low-income earners, many of whom were immigrants. Garden City ideas emphasized neighborhood planning that provided plentiful open green spaces and that encouraged community consciousness through unique placement of housing and amenities.[14]

A major facet of the RPAA’s ideals was the belief that home ownership would improve lives both physically and mentally. Low-income families suffering in squalid conditions in small rented apartments would not only be driven to maintain the homes they owned and make them better places to live in but would also be driven to take care of themselves and become involved in their communities, becoming upright, informed, and moral citizens.[15] To this end, the CHC was created, with Sunnyside Gardens as its first project. On the seventy-seven acres it bought, the CHC also strove to create housing at the lowest possible cost. This was not only to permit affordable housing prices for its target group, low-income earners, but also to make investment in Sunnyside Gardens profitable as lower costs yielded higher returns (since the U.S. government was not as involved in housing construction then as it is now, private investment was necessary to fund the development).[16]

The Design

The design of Sunnyside Gardens was commissioned to architect Clarence Stein and planner Henry Wright, while Frederick Ackerman, another architect, and the landscape architect, Marjorie Cautley, were also greatly involved in the design process. Built from 1924 to 1928, Sunnyside Gardens comprised of rows of one-, two- and three-family houses and cooperative apartment buildings built on sixteen blocks that could accommodate approximately 1,200 families.[17] To reduce costs, houses were built in a plain manner and with ordinary but strong materials such as brick.[18] The development filled approximately only twenty-eight percent of the land, leaving the rest as open space in the form of communal courtyard gardens on top of private yards for residents to enjoy.[19] To establish and protect the gardens, the CHC included forty-year covenants and easements in the property deeds that prevented residents from building garages or additions to their homes to changing the color of paint on the facades.[20] As a testament to the predominance of Irish residents, one resident noted that covenants and easements restricted doors to being painted green “because [Sunnyside Gardens] was predominantly Irish, and the Irish like green!"[21] Sunnyside Gardens also included the Phipps Garden Apartment buildings, two courtyard apartment buildings that were built in 1932 and 1935, as well as Sunnyside Park, a private park available only to those who paid members’ dues. Construction of Sunnyside Gardens ultimately yielded a suburban-like environment in an overwhelmingly urban one.

The designers consciously created Sunnyside Gardens so it would encourage social mixing and promote community health and involvement. The mixture of different housing types such as owner-occupied homes and renter-occupied apartments was to ensure regular contact between residents of different social backgrounds (specifically between the lower-middle- and middle-class who were more likely to own and the working-class who were more likely to rent).[22] Houses were built to prevent crowding despite being built closely together, and to ensure sunlight (through many windows) and access to the surrounding courtyards so as to protect residents from the issues of overcrowding and the lack of sanitation and space prevalent in Manhattan and other parts of the city.[23] The position of houses close to the perimeter of the block and their construction in “perimeter rows”[24] not only reduced construction costs but also allowed for larger spaces behind the houses in the interior of the block to create shared courtyard gardens that could be accessed through pathways from the street.[25] These common gardens would promote unity among residents through providing spaces for group activities and would thereby serve as roots for community and political activism.[26] The housing of Sunnyside Gardens would not only be physically better but its environment would also be socially and politically more stimulating for low-income residents than what they had experienced in previous homes and neighborhoods.

From 1928 to 1968

Although its designers intended Sunnyside Gardens to serve low-income residents, early residents tended to be lower middle-class or solidly middle-class. Homes were still too expensive for most low-income earners despite CHC’s cost-cutting efforts.[27] However, early residents did arrive from a variety of socioeconomic backgrounds. They lived next to mechanics, office-workers, tradesmen, and several writers, artists, teachers, doctors and other professionals.[28] Many were also immigrants and tended to be Irish and Germans moving from the cramped conditions of the Lower East Side of Manhattan.[29]

With the Great Depression, however, economic hardship resulted in residents carrying out a rent and mortgage strike that did not succeed in adjusting payments and instead led to evictions, causing population turnover.[30] From the end of World War II to the 1960s, artists and families with young children or those who sought children moved to Sunnyside Gardens, which became known as the “maternity ward of Greenwich Village,”[31] since the new residents left cramped and expensive Manhattan for Sunnyside Gardens’ larger, cheaper, and more child-friendly spaces.[32] By 1960, Sunnyside Gardens became more strongly middle-class and included those Irish, Jewish, and German descendents of immigrants who could not afford to live in Manhattan.[33] The strong Irish presence throughout the history of Sunnyside Gardens and Sunnyside in general also helped to contribute to the neighborhood’s traditionally Irish leanings, which still survive despite Sunnyside’s multi-ethnic demographics today.

Division from 1968 to the Present

Despite – or because of – the grand vision of the RPAA and the CHC, Sunnyside Gardens had become a divided community, especially in light of its recent landmark status dispute. The division began when CHC’s covenants and easements expired in 1968. Soon after their expiration, many residents – especially those who were not the original residents – began to alter their houses, build driveways and garages, and enclose parts of the common gardens for themselves, which sparked conflict with the more preservation-oriented residents, who saw the changes as threatening the original communal vision of the development.[34] [35] Although New York City designated Sunnyside Gardens as a Special Planned Community Preservation District in 1974 – which prohibited residents from making alterations to their homes and the communal gardens without a special permit – to respond to those tensions, preservationists nevertheless felt that the designation did not go far enough. Rules under the designation did not mandate the removal of alterations made before 1974 and were felt by preservationists to be weakly enforced as some residents continued making illegal alterations anyway.[36][37] Preservationists, led by the Sunnyside Gardens Preservation Alliance, began to push for the designation of Sunnyside Gardens as a historic district, perceiving city landmark status to provide stricter regulation on alterations, with a formal bid beginning in 2003.[38][39]

Although the majority of residents supported landmark designation, a vocal minority opposed it. Represented by the organization, Preserve Sunnyside Gardens, the minority stated concerns with higher home repair costs (as repair efforts could not risk changing the original appearance of homes without stringent fines), loss of community power to the Landmarks Preservation Committee (a Manhattan-based organization), misguided regulation (which would protect the architecture rather than the shared gardens that characterized the development), and excessive regulation (as many opponents felt that the 1974 designation was already restrictive and protected the neighborhood thoroughly).[40][41] Those opposed to landmark designation also cited the negative impact landmark status would have on immigrants[42] specifically (as stated before, over sixty percent of Sunnyside’s residents are foreign-born) and the working-class and middle-class generally, who would be priced out of Sunnyside Gardens (as landmarked areas are typically more expensive to live in than other areas,[43] most likely due to maintenance costs), and in turn, negate the development’s purpose of providing housing for working- and middle-class individuals. Hunter College professor Susan Turner-Meiklejohn, an opponent of landmark status, even declared that those in favor of landmark designation were likely “old-timers” that just wanted to stem the recent massive inflow of immigrants to Sunnyside.[44]

These differing views of landmark and anti-landmark supporters on what would protect the vision of Sunnyside Gardens had led to tensions among residents that the development’s designers explicitly wanted to avoid. Residents “have been caught in the courtyard taking pictures [of their neighbors' homes] and reporting them for violations,"[45] while one’s man opposition to landmark designation has resulted in neighbors’ complaints and a stop-work order on construction at his home.[46] In late October of 2007, however, the City Council unanimously agreed to the Landmark Preservation Committee’s unanimous approval of Sunnyside Gardens as a historical district.[47] Though it is still too soon to determine, the new landmark status might have detrimental effects on current residents – of which many are immigrants or their descendents – and their ability to continue living in Sunnyside Gardens, should living costs rise as a result of the new designation.

Go to Creative Accent.

References

- ↑ Richard Weir, "A Queens Version of Gramercy Park, With Barbecues," New York Times, 3 May. 1993, 18 Mar. 2009 <http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9506E3DF103EF930A35756C0A96E958260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=print>

- ↑ Jeff Vandam, "An Enclave at Once Snug and Inclusive," 4 Feb. 2007, New York Times, 18 Mar. 2007 <http://www.nytimes.com/2007/02/04/realestate/04livi.html?sq=sunnyside&st=cse&scp=1&pagewanted=print>

- ↑ Place in History, “Sunnyside Gardens Neighborhood History,” Place in History, Place in History, 2000: 2, 14 Mar. 2009<http://www.placeinhistory.org/proof/projects/sunnyside_gardens/>

- ↑ Christopher Gray, “A Walk on the Sunnyside Street,” New York Times, 13 Mar. 2005, 14 Mar. 2009 <http://www.nytimes.com/2005/03/13/realestate/13scape.html?sq=sunnyside&st=cse&scp=4&pagewanted=print&position=>

- ↑ Sunnyside Gardens Preservation Alliance, "History," Sunnyside Gardens Preservation Alliance, 6 Apr. 2009 <http://www.sunnysidegardens.us/history/history.html>

- ↑ Queens Library

- ↑ Julia Vitullo-Martin, "A Pioneering Queens Garden Community Flourishes Anew," New York Sun, 7 Jul. 2005, 6 Apr. 2009 <http://www.nysun.com/real-estate/pioneering-queens-garden-community-flourishes-anew/16589/?print=2228157321>

- ↑ Gray

- ↑ Jeff Vandam, "Brick Houses, Winding Paths and Unexpected Sharp Elbows," New York Times, 31 Dec. 2006, 25 Mar. 2009 <http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9A06EFD61F31F932A05751C1A9609C8B63&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=print>

- ↑ Gray

- ↑ http://www.placeinhistory.org/proof/projects/sunnyside_gardens/

- ↑ http://www.placeinhistory.org/proof/projects/sunnyside_gardens/

- ↑ New York City, Landmarks Preservation Commission, Sunnyside Gardens Historic District: Designation Report, New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, 26 Jun. 2007: 19, 7 Apr. 2009 <http://www.nyc.gov/html/lpc/downloads/pdf/reports/SunnysideGardens.pdf>

- ↑ New York City 19

- ↑ New York City 23

- ↑ New York City 28

- ↑ New York City 25-26

- ↑ Place in History 6

- ↑ New York City 6

- ↑ New York City 32

- ↑ Place in History 2

- ↑ New York City 27

- ↑ Place in History 6

- ↑ New York City 27

- ↑ New York City 27

- ↑ Place in History 2

- ↑ New York City 31

- ↑ New York City 31

- ↑ New York City 31

- ↑ New York City 37

- ↑ Marcus W. Brauchli, “If You’re Thinking of Living in: Sunnyside,” 3 Jul. 1983, New York Times, 13 Mar. 2009 <http://www.nytimes.com/1983/07/03/realestate/if-you-re-thinking-of-living-in-sunnyside.html?sec=&spon=&pagewanted=print>

- ↑ New York City 31

- ↑ New York City 31

- ↑ Place in History 8

- ↑ Christopher Gray, “A Walk on the Sunnyside Street,” New York Times, 13 Mar. 2005, 14 Mar. 2009 <http://www.nytimes.com/2005/03/13/realestate/13scape.html?sq=sunnyside&st=cse&scp=4&pagewanted=print&position=>

- ↑ Place in History 1

- ↑ Eliot Brown, “Landmarking Battle Divides Residents of Sunnyside,” New York Sun, 5 Mar. 2007, 20 Mar. 2009 <http://www.nysun.com/new-york/landmarking-battle-divides-residents-of-sunnyside/49773/>

- ↑ Tom Angotti, “Sunnyside Fights over What to Preserve,” Gotham Gazette, Apr. 2007, 20 Mar. 2009 <http://www.gothamgazette.com/article/landuse/20070411/12/2145>

- ↑ Ellen Barry, “Area of Sunnyside, Queens, Is Given Landmark Status,” New York Times, 27 Jun. 2007, 23 Mar. 2009 <http://www.nytimes.com/2007/06/27/nyregion/27sunnyside.html?sq=sunnyside&st=cse&scp=11&pagewanted=print>

- ↑ Brown

- ↑ Warren Lehrer, Letter, New York Times, 7 Jan. 2007, 20 Mar. 2009 <http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9C00E3D61430F934A35752C0A9619C8B63&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=print>

- ↑ Ellen Barry, “A Pocket of Queens Brimming with History, And Now Resentment,” New York Times, 5 Jul. 2007, 13 Mar. 2009 <http://www.nytimes.com/2007/07/05/nyregion/05sunnyside.html?pagewanted=print>

- ↑ Tom Angotti, “Sunnyside Fights over What to Preserve,” Gotham Gazette, Apr. 2007, 20 Mar. 2009 <http://www.gothamgazette.com/article/landuse/20070411/12/2145>

- ↑ Angotti

- ↑ Magdalene Perez, “Sunnyside Landmark Status Divides Nabe,” amNewYork, 14 Jun. 2007, 25 Mar. 2009 <http://www.newsday.com/travel/am-sunny0615,0,6148470.story>

- ↑ Barry A Pocket of Queens

- ↑ David Freedlander, “Sunnyside Gardens Landmarked,” amNewYork, 30 Oct. 2007, 2 Apr. 2009 <http://www.orlandosentinel.com/news/local/am-sunny1030,0,5296731.story>

This page was created by Amy Lu.