From The Peopling of New York City

History -- Culture -- Demographics -- Landmarks and Attractions -- Economy

HISTORY

An infamous and historically rich area of Chinatown is what was once renowned as the Five Points in the 1800’s. The intersection of Anthony Street (now Worth), Orange Street (now Baxter), Mulberry Street (which is still the same), and Cross (now Moscow Street/Park Row) was the heart of one of the worst slums in the history of New York, for the most part inhabited by a mixture of African Americans, and German, Irish, and Italian immigrants. How did the slum come to be? Before becoming the Five Points, the Collect Pond (also known as the Fresh Water Pond) defined the area; one of the few water sources in New York City up until the early to mid 1700’s.

[1] At the time the area was home to a large population of African Americans, proven by the discovery of the African burial ground near City Hall in 1991, containing approximately 10-20 thousand burials, and estimated to have covered 4-5 acres.

[3] The area was tainted with blood early in its history. Following the “Negro Plot” or New York Conspiracy of 1741, in which poor whites and black slaves attempted to revolt and take control over the city, thirteen blacks were burned at stake between the intersection of Pearl and Chatham streets, and twenty were hung on an island in the Collect Pond.

[4] The area was already growing bad reputation, as “only the poorest class of houses were built on the low, marshy grounds in this vicinity, already claimed by poverty and crime.”

[5]

As the city developed, the Collect Pond was surrounded by more and more pottery works, tanneries, tobacco merchants, rope works, and slaughterhouses, which polluted the pond.

[6] In 1785, the New York Journal described the pond as “a very stink and common sewer”.

[7] The city decided to start draining the pond in 1802, by leveling Bunker Hill and filling the pond with construction debris and garbage. This in turn provided large-scale public work jobs for thousands of sailors and laborers out of work due to the Embargo Act. As a result of the rising land values, the rate of development accelerated, speeding the completion of the project (which was finished in 1815).

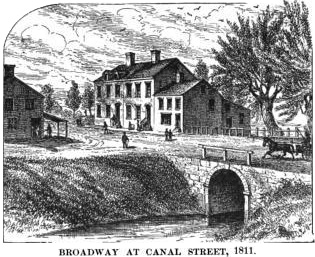

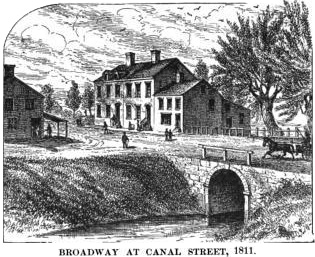

[8] Another result of the “filling” of the Collect Pond was the creation of a canal to relieve the occasional flooding of the low-lying marshland, which lay along the present day Canal Street.

Canal Street before the canal was made into a sewer.

[9]

The canal was kept in place until 1821, when it was covered up and turned into a sewer due to the potent scent and sanitary reasons. [10] Although the physical conditions of the area and pre-existing African-American population already warranted the area being labeled as a “slum”, the influxes of immigrants that followed had an incredibly powerful socio-economic impact on the area (and on New York and the U.S. as a whole).

The rough order of arrival of large immigrant groups in the Five Points is the following: Germans, Irish, Italians, and finally the Chinese, along with the more recent wave of Hispanic immigration that began in the 1990’s. The Great Migration of Irish immigrants, which began in 1845 due to the Irish Potato Famine, had a dramatic effect on the social and economic make-up on New York City. This was especially true in areas of the Lower East Side, such as the Five Points. Approximately 1.8 million Irish immigrated to the United States and Eastern Canada between 1845 and 1855.

[11] The majority of these immigrants were poor, Catholic, Gaelic-speaking farmers fleeing starvation and disease as they had lost their main source of nutrition: the potato. Many of the Irish Immigrants paid for their passage through money sent from relatives working in the U.S.

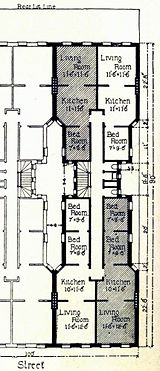

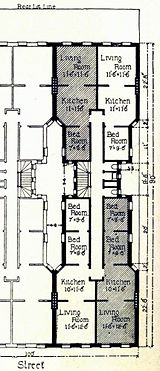

[12] These immigrants moved into tenement houses, such as those at the Five Points. The Lower East Side tenement houses have passed down through generations of lower class immigrants residing in the Lower East Side (LES), and are now historically infamous for their crowded and unsanitary conditions. The tenement buildings were usually 4-5 floors high. Once example of a tenement buildings were those built in lots 25 x 100 feet (see tenement floor plan), with small, un-ventilated court-yards or worse, without any space from one building to the next at all. This meant very few windows, ventilation and light. There was often no running water in these buildings, which made clean and healthy living conditions near impossible. Most of the time, several families would share a living room/kitchen space. Currently, many tenements have been replaced with newer buildings over time.

Floorplan of a standard tenement apartment.

[13] (Many Chinatown inhabitants continue to live in these tenements, though most have now been equipped with running water).

The poverty in the 5 points area led to increased gang activity, violence, and prostitution. However, alongside the hectic and violent atmosphere, many Irish immigrants were working hard to bring their families up the social ladder. When famine passed and the decedents of Irish immigrants spent several generations in the United States, they became an integrated part of American society, no longer excluding themselves to segregated communities. Though many Irish-Americans hold ties to their ancestral homeland, they no longer occupy the bottom lower class.

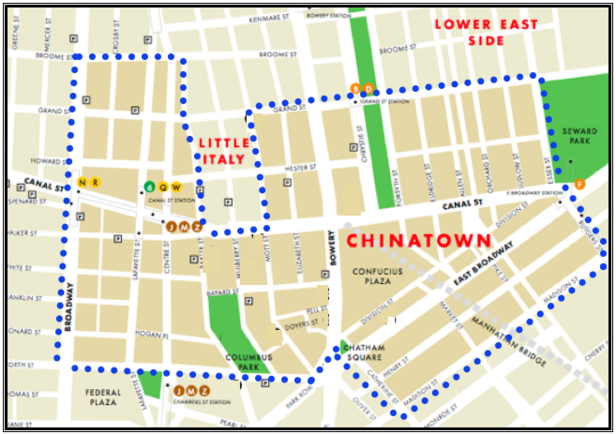

Italian immigrants, a more recent immigrant group, left a prominent imprint on what would become the Chinatown area: Little Italy. Little Italy is now only a few streets enclosed by Chinatown: Canal Street forms the southern border, while Baxter Street and Mott Street form the western and eastern borders respectively. Though now a mostly commercial area with few Italian residents, Little Italy was once significantly larger and is an important historical aspect of the Chinatown area. Large numbers of Italians, mostly Catholic, began to arrive in the United States, and particularly New York, toward the end of the 1800’s and continued to arrive into the early-mid 1900’s. Between 1860 and 1880, 68,500 Italians came to New York, and 391,000 Italians lived in New York City by 1920.

[14]

An aerial view of a typical east-side block at the time

[15]The vast majority of Italian immigrants were searching for work because they were not able to make a living in Italy. This is shown by the fact that up until 1900, 78% of Italian immigrants were men in their teens and twenties, looking to work, make money and then head back home. About 20-30% did so, but the rest of the Italian immigrants stayed and settled permanently.[16] Italian immigrants formed little enclaves, such as this little Italy, to be protected from discrimination by the Irish and German groups. These enclaves were dominated by Italian businesses and shops, such as bakeries, taverns, and men and women selling food and fruit in carts.[17] Even amongst the Italians themselves there was significant separation: Northern Italians settled along Bleeker Street, the Geonese occupied Baxter Street, and Western Sicilians tended to live along Elizabeth street.[18] However, as immigration from Italy slowed and generations passed, Italians became integrated into American society and the need for extreme cultural separation was no longer necessary. Currently, Little Italy is no longer a poor immigrant neighborhood but mainly a tourist attraction with traditional Italian bakeries and pricy restaurants.

The California Gold Rush in 1848 marked the arrival of Chinese immigrants to the west coast of the United States. However, as gold became scarce and the competition too high, the Chinese began to enter other industries in the west, such as cigar-rolling. This angered “natives” (referring not to Native Americans but American-born citizens who, presumably, had family in the United States for several generations back) who claimed the Chinese were stealing their jobs and spiked racism. As a result, many Chinese traveled east and to metropolitan cities to avoid this racism. New York was one of the places where many of these Chinese immigrants went to live. They resided in tenement housing because it was the cheapest option and all they could afford. Many Chinese opened small businesses. Laundry for example, became a predominantly Chinese business.

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 blocked Chinese labor immigration but also impeded non-laborious immigration because permission from the Chinese government was required for entry, which was very hard to get.[19] Men who had come to work in the Untied States could not to bring their wives and family over and a result, New York’s Chinatown became known as a “Bachelor’s society”, full of opium dens and prostitution. This only heightened antagonism and stereotyping of Chinese immigrants. Congress slowly relaxed its barriers on Chinese immigration by setting quotas in 1945 (only 105 Chinese permitted a year), and relaxed slightly more in 1965 by giving a yearly quota of 170,000 immigrants outside the Western Hemisphere. Then, finally in 1990, Congress passed a law that “established a ‘flexible’ worldwide cap on family-based, employment-based, and diversity immigrant visas.” [20] As a result of a relatively more relaxed immigration policy, Chinatown has grown as a community and a business district, extending its physical boundaries and becoming an attraction for tourists and New Yorkers alike.

Map of the Collect Pond in relation to the streets created after the pond was filled. [21]

|

Map of Lower Manhattan in 1880s, which includes the area of Chinatown before it became Chinatown. Note Canal Street which still exists to this very day. [22]

|

Chinatown used to be a small area, but expanded as more Chinese people migrated to New York City. [23]

|

1920s Map of Lower Manhattan and in the center is Chinatown. [24]

|

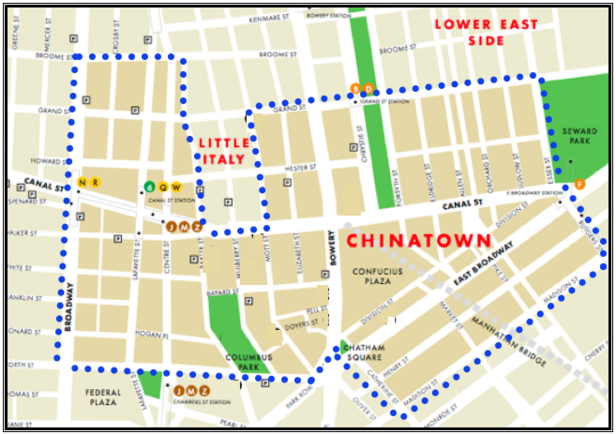

Map of Chinatown today.

[25]

References

- ↑ Gandy, Matthew. Concrete and Clay: Re-working Nature in New York City. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002.

- ↑ Chin, Rk. "The Neighborhood that was the Five Points (19th Century)." A Journey Through Chinatown. 2 Apr 2008 <http://www.nychinatown.org/history/1800s.html>.

- ↑ Chin, Rk. "The Neighborhood that was the Five Points (19th Century)." A Journey Through Chinatown. 2 Apr 2008 <http://www.nychinatown.org/history/1800s.html>.

- ↑ Ladies of the Mission Staff, The Old Brewery and the New Mission House at the Five Points. Manchester, NH: Ayer Publishing, 1854.

- ↑ ibid

- ↑ Aleandri, Emelise. Images of America: Little Italy. Mount Pleasant, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2002.

- ↑ see Gandy

- ↑ see Gandy

- ↑ Chin, Rk. "The Neighborhood that was the Five Points (19th Century)." A Journey Through Chinatown. 2 Apr 2008 <http://www.nychinatown.org/history/1800s.html>.

- ↑ see Chin

- ↑ "Home for the Heart: The Story of Irish Immigration." American Immigration Law Center Exhibit Hall. 24 May 2002. American Immigration Law Foundation. 3 Apr 2008 <http://www.ailf.org/exhibit/ex_irishim.htm>.

- ↑ ibid

- ↑ Lienhard, John H.. "No. 2137: Tenement Houses." Engines of Our Ingenuity. 1998. University of Houston. 20 Apr 2008 <http://www.uh.edu/engines/epi2137.htm>.

- ↑ Hall, Kathryn. "Little Italy: Neighborhood in New York City." New York City Tour. Inetours. 2 Apr 2008 <http://www.inetours.com/New_York/Pages/Little_Italy.html>.

- ↑ see Lienhard.

- ↑ "The Story of Italian Immigration." 17 May 2004. The American Immigration Law Foundation. 4 Apr 2008 <http://www.ailf.org/awards/benefit2004/ahp04essay.asp>.

- ↑ ibid

- ↑ see Hall

- ↑ "Chinese Exclusion Act (1882)." Our Documents. Government of the United States. 3 Apr 2008 <http://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=true&doc=47>.

- ↑ see "Our Documents"

- ↑ Costello, Augustine E. Our Firemen: A History of the New York Fire Departments, Volunteer and Paid, from 1609 to 1887. Knickerbocker Press, 1997.

- ↑ "U.S. Historical City Maps." University of Texas Libraries. 09 Apr 2008 <http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/historical/manhattan_topo_1880.jpg>.

- ↑ Wong, Bernard. Chinatown Economic Adaptation and Ethnic Identity of the Chinese. New York: CBS College Publishing, 1982.

- ↑ "U.S. Historical City Maps." University of Texas Libraries. 9 Apr 2008 <http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/historical/manhattan_lower_1920.jpg>.

- ↑ "Explore Chinatown New York City." Explore Chinatown Map. 09 Apr 2008 <http://www.explorechinatown.com/Gui/Content.aspx-Page=Locate.htm>.

[[History]] [[Culture]] [[Demographics]] [[Landmarks and Attractions]] [[Economy]]