History

The History of Chinatown

The History of Chinatown

New York’s Chinatown started growing in the 1870’s following the passage of the Burlingame Treaty of 1868. The Burlingame Treaty gave China the status of Most Favored Nation and also provided that citizens of either the US or China could travel and study freely in the ot

Following the exclusion act, new immigration largely stopped, but Chinatown kept growing as a result of an influx of Chinese men already in America. Many of the early Chinese immigrants worked in the western states on the transcontinental railroad, and as violence towards Chinese increased in the 1870s, they started moving into New York’s Chinatown.

In the 1890’s Chinatown was basically a 3-block enclave consisting of Pell, Doyer, and Mott Streets. As more and more Chinese moved into Chinatown, the enclave expanded. Contemporary observer Louis Beck described the expansion of Chinatown as follows: “the lower end of Mott Street very quickly filled with Chinese…Gradually, the colony increased and spread into Doyer Street. Until now the entire triangular space bounded by Mott, Pell and Doyer Streets and Chatham square is given the exclusive occupation of these orientals, and they are fast acquiring possession of Bayard street”(Wan, 26).

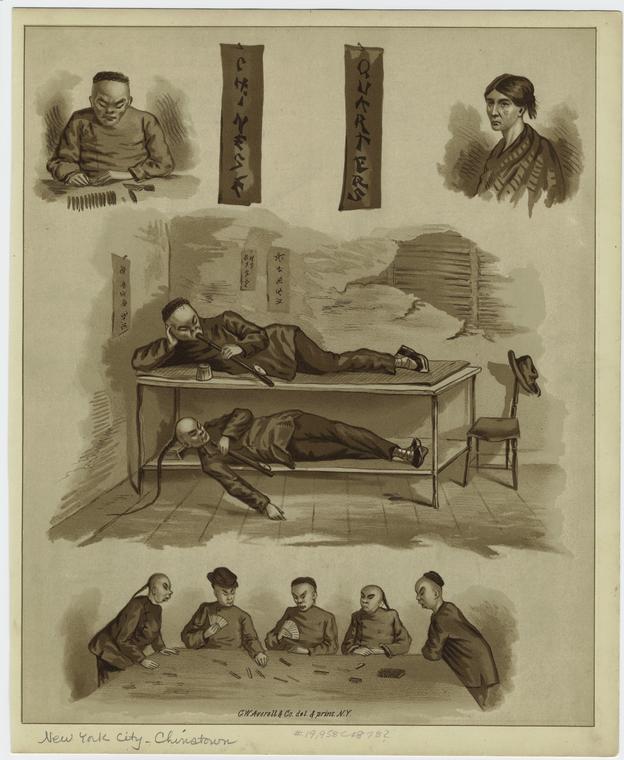

The ratio of men to women in New York’s Chinatown was twenty-seven to one, the only women visible on the streets were servant girls and white prostitutes, and all but 84 men were ”bachelors” (many of these had wives back in China). According to one journalist’s account, in 1898, Chinatown, with a population of around “ three thousand, had seven hundred gamblers, four hundred and fifty hatchet men, one hundred and seventy-five merchants, seventy-five cigar makers and seventy-five vegetable growers, forty-five restaurateurs, forty-five pastry chefs, at least 20 opium dens, one annual opera, and yearly poetry writing competitions (Kinead, 48-49).

The opium “dens” and prostitution gave Chinatown a bad reputation. Unfortunately, New Yorkers in the early 1900’s did not quite perceive Chinatown as the safe haven that it represented to many Chinese men. This in turn made New Yorkers see Chinatown as “an enclave of vice and danger to white womanhood” (Lui). The association of Chinese with opium at this time cast a negative light on the area. White New Yorkers described Chinatown as a dirty and smelly place that was dangerous especially to white women. In this era, journalists and other observers claimed that such women could easily become opium addicts.

Still, the police often overlooked many of the gambling halls, opium dens, and the prostitution, allowing the Chinese to settle their own affairs as long as these affairs did not involve whites. Chinese organizations known as “tongs” often managed the vice industry, and when they clashed with each other, white policemen usually stayed away. This is part of why many New Yorkers feared Chinatown and came to see the Chinese as an inferior society.

In the 1900’s, China’s economic problems pushed many Chinese to continue to view America as a place of opportunity, and thousands entered through both legal and illegal channels. However, most viewed America only as a temporary home that would allow them to make some money and return to China to live a better life. In the years before World War Two, few could bring their families to the United States, further cementing this “sojourner” mentality. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, many of the former sojourners gave up the dream of going back to their home country and decided to settle permanently in the U.S.

In 1943, the United States Congress passed and President Roosevelt signed the Magnuson Act, also known as the Chinese Exclusion Repeal Act of 1943. It allowed Chinese immigration for the first time since 1882. Although the act only set a quota of 105 Chinese immigrants a year, it was the first step towards a more liberal immigration policy. The number 105 was derived from original formula of the Immigration Act of 1924, which allowed a total of 2% of the people of that origin already living in the United States in 1890. In 1945, the Chinese War Brides Act allowed thousands of China-born wives of US citizen veterans to immigrate to US as non-quota immigrants. Since New York’s Chinatown was becoming one of the largest Chinese enclaves, many of these new immigrants settled in Chinatown.

In 1965, the Immigration and Nationality Act abolished the quota system and allowed 20,000 new Chinese immigrants a year to legally enter and become citizens of the United States. Chinatown began to expand, spilling into Little Italy and parts of the Lower East Side. In the years between 1965 and 1990, the Population of Chinatown increased from 20,000 to 95,000, making New York’s Chinatown the largest Chinese enclave in the Western hemisphere. While information from the 2010 Census is not available yet, it is estimated that the population of New York’s Chinatown has grown to over 100,000.

Sources:

1. Enoch Yee Nock Wan, The Dynamic of Ethnicity: A Case Study on the Immigrant Community of New York Chinatown

2. Gwen Kinead, Chinatown: A Portrait of a Closed Society

3. Kenneth J Guest, God in Chinatown: religion and survival in New York’s evolving immigrant community (New York: New Your University Press, 2003)

4. Kenneth T Jackson, The Encyclopedia of New York City (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1995), Chinatown

5. Mary Ting Yi Lui, The Chinatown Trunk Mystery: Murder, Miscegenation, and Other Dangerous Encounters in Turn-of-the-Century New York City

6. Museum of Chinese in America, Hystory of Chinese in America: An Interactive Timeline

Images:

1. New York City's Chinatown decorated for New Year (1909). (Image from Library of Congress)

2. Chinatown sleeping quarters (1878). (Image from NYPL Digital Library)

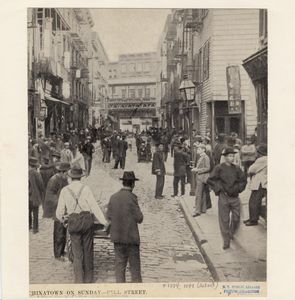

3. Chinatown on Sunday-- Pell St. (1899). (Image from NYPL Digital Library)

4. Chinese School on Mott Street (1879). (Image from NYPL Digital Library)